On the Timely Racial Politics of The Royale

The Royale, currently playing at Lincoln Center’s Mitzi E. Newhouse theatre, is—if you’ll pardon the pun—a knockout. Marco Ramírez’s play follows Jay “The Sport” Jackson (Khris Davis), an African American boxer who dreams of challenging the current world heavyweight champion to crown himself the unchallenged winner he knows himself to be. The catch? We’re in 1905 and the reigning white titleholder, Bernard “The Champ” Bixby, will need some careful coercing to accept a challenge from a black boxer at a time when Jim Crow was still the law of the land. Staged with minimalist gusto, The Royale pulsates with timeliness in a time when #BlackLivesMatter, racial hatred, and even the Ku Klux Klan continue to make headlines, reminding us that half a century’s worth of Civil Rights progress belies the fight that many African Americans continue to wage daily in this country.

Staged with minimalist gusto, The Royale pulsates with timeliness in a time when #BlackLivesMatter, racial hatred, and even the Ku Klux Klan continue to make headlines.

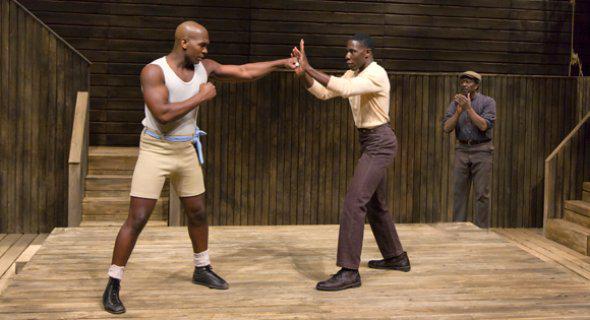

Based on the real life events of boxer Jack Johnson, Ramírez has structured his piece like a fight in six rounds. Nick Vaughan has turned the stage into a boxing ring where theatregoers become inadvertent boxing enthusiasts. The play opens when Jackson is introduced to the audience as he’s about to fight rookie newcomer Fish (McKinley Belcher III). We quickly get to see that “The Sport” is a charming boxer whose knockouts come laced with (and are empowered by) his cracking wit. This bravado, which so ingratiates him with the crowd, as his trainer Wynton (Clarke Peters) and his manager Max (John Lavelle) remind us, is what also makes him exceedingly cocky, at times unable to see beyond the punch he’s about to deliver.

During Jackson’s first fight, and in a conceit that will continue throughout the play, we get to hear the boxers’ inner monologues. Jackson, confident and self-assured, feels these fights he’s been getting lately are all too easy and not worth his time; Fish, terrified but hopeful, garners plenty of laughs as the prospect of knocking out “The Sport” becomes (if ever so briefly) a possibility. Director Rachel Chavkin deserves great praise from matching a blood-spilling sport with a balletic sensibility. This first round, which ends, of course, with Jackson winning, teaches the audience that while this is a show about boxers, we won’t be witnessing any punches. Instead, Davis and his fellow actors use movement and rhythm to suggest the blows that are exchanged in the ring: “During the ‘fight’ sequences,” the play informs us, “both boxers should face the audience, not each other, and there is no need to swing.” Foot stomps and handclaps become the soundtrack for this story, putting us in Jackson’s headspace. As Ramírez puts it in the Foreword to his published play, he “wanted somehow to put all of us in the boxer’s head, so that when he said ‘Here comes the knock-out,’ the entire audience felt like they were swinging with him.” It’s a successful gambit that allows boxing to become a fluid metaphor in itself.

Ramírez turns this symbolic fight between black and white into a more complicated affair, where the blood and taunts of black and white men alike build up to a devastating indictment of the racial divide that remains all too timely.

The arrival of Jackson’s “fierce big sister,” Nina (Montego Glover), turns The Royale into a dissection of the heated racial politics surrounding his upcoming fight. Dressed impeccably in her Sunday best, Nina announces the entrance of the outside world into the confined purview of the boxing ring. Jackson, who sees in his eventual victory a victory for and about his race, is confronted with the reality that even as many are cheering for him, racially-motivated violence is escalating. Thus, as the piece—which is presented without an intermission—moves towards the inevitable face-off between Jackson and Bixby, Ramírez turns this symbolic fight between black and white into a more complicated affair, where the blood and taunts of black and white men alike build up to a devastating indictment of the racial divide that remains all too timely. Jackson, breaking through one type of glass ceiling, may very well function as an Obama stand-in, whose victory beckoned hope and rage in equal regard. Just as Jackson was becoming a symbol for progress, he in equal measure became a target for resentment:

NINA: In the middle of the title-fight heavyweight champion nonsense have you stopped to think, for one second—

That you gon’up’n get somebody killed?

…

I think you’re so caught up in playing David to Goliath,

In being the one fish swimming upstream,

I think you up and forgot about the rest of us,

The ones ain’t as strong as you.

Nina doesn’t want Jackson to lose, but she’s afraid of what’ll happen when he wins. The conversation they have—the fifth “round” in the play—features no punches and yet it is the most grueling to watch. At heart, what The Royale does in this scene is stage the central issue of the burden of representation. Nina stresses how Jackson has forgotten what he’s left behind in seeking his individual glory, but Jackson sees himself as the beacon of other possible futures for men like himself. And for her. In the sixth round, when Jackson goes head to head with Bixby, it is Glover as Nina who takes his place, delivering and taking the blows shared between the two boxers: a stark reminder that “The Sport” is fighting for and against his sister’s interest. As he recounts a shared memory of her as a young girl burning her scalp while ironing her hair (“’Cause she ain’t never seen no posters look like her”), she narrates the violence that’s bubbling up around (“Somewhere close. There’s a hand on a knife”), that which will inevitably end up spilling blood outside the ring by the time the lights dim. Despite the victory we witness in the ring, we’re left bewildered, lacking the comfort of a soothing happy ending. Alas, the play is over so we’re left with no other choice but to burst into an applause that cannot help but champion character and performer alike, further making us complicit in the play’s intentionally prickly politics.

It is that final round that really makes The Royale resonate in 2016. Here is a tale of painful progress. Of deterred and delayed dreams. Of a fight “two hundred years in the making” that remains all too relevant a hundred years later. Ramírez notes that he decided to change the name of his boxer since, other than borrowing the main beats of Johnson’s life, he had crafted a larger story, one that stood in for the many other underdogs that had followed in his footsteps. For him, Jackson isn’t just Johnson. He’s Muhammad Ali, Miles Davis, Jay Z, and other “underdogs” who got out and ahead, who conquered the world in spite of the establishment. In crafting this lineage, “The Sport” is a reminder that even today there is an ongoing fight with no knockout in sight. As Nina reminds us at the end, this victory will come at a cost—“This ain’t s’posed to be easy.” It’s a gut-punch of a closer that hits harder than anything else in the show. One that makes us, as Ramírez hopes, curl our fingers into a fist, hoping we too can just knock this ghastly racism out of the United States.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here