Painting It Out

The Living News Project’s SHELTER/CHICAGO

I see one-third of a nation ill-housed, ill-clad, ill-nourished. But it is not in despair that I paint you that picture. I paint it for you in hope—because the nation, seeing and understanding the injustice in it, proposes to paint it out.

—Franklin D. Roosevelt, Second Inaugural Address, 1937

When I was eleven years old I created a flowchart on my wall, with the President of the United States at the top, and me at the bottom. In between were senators, members of Congress, the mayor of New York, and Neil Armstrong. I embarked on a letter writing campaign to find out about their jobs, assuming that with their answers I could map out how it all works, where I belong, and what I should do in the world. My heart beat fast with each envelope, embossed seal, and signature as if it had sacramental power. Though the experiment was a flop (I couldn’t figure it all out), the letters gave me tangible proof that I was somehow connected.

Points of connection are more elusive now. The news is supposed to help us to understand our place but the 24-hour blast-stream of information, often served up in small bits devoid of context, can be disorienting, fear inducing, confusing. How are we supposed to know where we fit? The Living News Project is an extension of my eleven-year-old flowchart—it’s fueled by the desire to find a way for us, as artists and citizens, to climb into the arena, take agency, reclaim the news.

The Living News Project’s SHELTER/CHICAGO: What It Is

In poetic documentary style, SHELTER/CHICAGO investigates the tangled knot of social and political causes leading to homelessness by listening to the stories of people living on our streets. Chicago journalists, artists, students and faculty at Columbia College Chicago, staff and residents at Cornerstone Community Outreach (CCO), and a homeless shelter in the city’s Uptown neighborhood are collaborating to create a journalistic theatre piece that challenges all of us to reconsider our perceptions and preconceptions about urban homelessness, to explore when, why, and how the media reports the story, and to question our responsibilities as citizens.

In 1935, when the federal government paid unemployed theatre artists to work with unemployed journalists, what emerged were large-scale plays that offered audiences an exciting, accessible alternative to the commercial theatre of the day. Living Newspapers focused on social and political issues.

The Inspiration: WPA Federal Theatre Project’s “Living Newspapers”

In an age of terrific implications as to wealth and poverty, as to the function of government, as to peace and war, as to the relation of the artist to all these forces, the theatre must grow up. The theatre must become conscious of the implications of the changing social order, or the changing social older will ignore, and rightly, the implications of the theatre.

—Hallie Flanagan, Arena: The Story of the Federal Theatre

In 1935, when the federal government paid unemployed theatre artists to work with unemployed journalists, what emerged were large-scale plays that offered audiences an exciting, accessible alternative to the commercial theatre of the day. Living Newspapers focused on social and political issues—the plight of the dust bowl farmers, the crisis in housing, affordable electric power—and for a short time they served, in a way, as our national theatre and a vital news feed. Living Newspaper productions toured the country, met by writing “units” in various cities that adapted the scripts to keep them local and up to date. They were always hot off the press. Arthur Miller called them “the greatest invention of theatre in our time.”

The Living Newspapers were not strict documentaries. Rather, they flipped from hard statistics to human interest stories revealing intimate scenes of “the little man,” to convey the effects headline stories had on individual lives. It is no wonder that this epic theatre style emerged, as Living Newspapers were the invention of Hallie Flanagan, the director of the Federal Theater Project, who admired the theatrical experiments of Bertolt Brecht and Erwin Piscator, and believed passionately that a Federal Theater Project should participate, unflinchingly, in the civic discourse of the country.

What would a twenty-first century Living Newspaper about homelessness look like? Once the question was voiced, I was already at work.

How It Started in Chicago’s Uptown

The tangible act of completing a homework sheet and sliding it into a kid's folder for the next day can be monumentally gratifying when that kid is living in the chaotic whirlwind of a shelter. As I was tutoring kids at Cornerstone Community Outreach, I listened to their stories, and knew they had to get out into the world.

What would a twenty-first century Living Newspaper about homelessness look like? Once the question was voiced, I was already at work. The big-hearted, overextended shelter staff gave me a green light and I was at the soup kitchen. “Hey, I am doing a play about homelessness.” Each time, it seemed so naïve as to be ridiculous. Burning through embarrassment and fear, I made posters and set up shop in the dining room eager to start conversations. For days, nobody talked to me. Some didn’t want their families to know they were there. Some offered to talk for money. Some just didn’t want to talk—why should they? One man got right up in my face and sloppily spit “You don’t want my story! Give me a bottle of 151 and I’m dead.”

Then persistence won out and the tide turned. One day my phone rang. “I’m so interested in what you’re doing.” Richard had seen my poster. He had no home but he had “so much to give.” His urgency flooded me with a sense of responsibility.

Another day, I held a tape recorder while a young homeless mother held back tears, recounting her own childhood “in the system,” and the abstract concept of the “cycle of poverty” burst into life for me through her gritty determination to break out of it.

A small writing team (a couple of reporters from the Chicago Tribune, and a few Columbia College Chicago students) poured over the footage and wondered how to begin. It was wilderness without a map. Recognizing the shelter whirlwind, we adopted a La Ronde-like structure of interlocking scenes, giving us some traction to build characters and knock out scenes based on interviews and news clippings. A few months later, we planned an informal read through of our draft at the shelter. We were excited.

That night after dinner, shelter residents and staff sat in a small circle of chairs with our writing team, reading out loud. It was a complete disaster. And there were no holds barred in the critique: It was all too prissy, too after-school-special-ey. It had none of the energy of the world we were trying to understand. I wanted to give up.

That night cracked the project open. Without intending to, I had fallen into a lot of traps.

1. I didn’t learn from the flowchart: we collected stories assuming that when we put them together they would lead to a linear understanding of the way things work.

2. As with so many “outreach” projects, we tried to make something without listening hard enough or long enough—without taking the time to build relationships.

And the most important realization:

3. That I was clinging to an old way of doing things, and I needed to let it go. I needed to relinquish expert status. My theatrical cleverness was not going to solve this. But my humanity might.

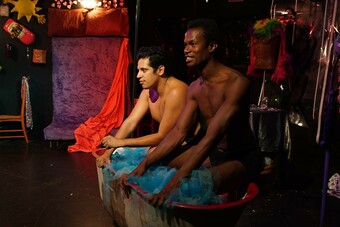

Back to the drawing board, the team got to work, collaborating much more closely with shelter staff and residents. Some residents joined the writing team, some performed on stage—a gritty model influenced by the work of Cornerstone Theater in Los Angeles, and notably divergent from the original 1930s scheme. The Living News Project web grew in every direction—more students and faculty, journalists, theatre artists of all kinds, activists and advocates, an ever-evolving, unwieldy passionate gang.

Field Notes and Three Invitations

Over the past three years, our work has been marked by six public readings and conversations, the script always fresh, “hot off the press.” Here are some field notes cataloguing discoveries and inquiries from the journey:

***

Stories don’t exist on their own, but in context. The story of the homeless woman having breakfast at the shelter exists in dialogue with the story of the neighbor down the street making coffee in their kitchen, or the alderman in the district office two blocks away trying to figure out how to get reelected, or the northside reporter trying to keep her job. It’s easy to fall into the mainstream media trap of taking stories as their own discreet meaning-making entities. But that isn’t real life. (click to view scene from SHELTER/CHICAGO)

What happens if we shift focus to the connections between the stories, instead of the stories themselves?

***

We’re critiquing the media. Shouldn’t we interview journalists? Can we interview the ward alderman? Neighbors?

***

A journalist told me that there is a tacit understanding that exists, an unspoken conversation: “We (journalists) don’t print news about homelessness because you (the public) don’t want to read it. If we simply don't print it, you don’t have to read it. We all relinquish responsibility.” Can we examine that, and bring it to the light of day?

***

If it’s a media circus we need a juggler.

***

What are our responsibilities to each other—citizens and journalists? A journalist told me her job is to “give people a reason to care.”

***

Any city dweller knows the moment on the street when we are asked for money. It’s a complicated unspoken conversation each of us has every day. What happens in that moment? How can we unpack it? What assumptions fuel us? What patterns have we created? Can we interrupt them?

***

Does this work matter? One night, I was scared to approach a man at the shelter because he looked tough—he was wearing a lot of leather, and had what I read as a “don't talk to me” vibe. He was sitting apart from the others. When I pushed passed my own fears, I found out that Lucky loved the idea of the play. The next morning, he called me on my cell phone to say he'd be at rehearsal that night. After watching the whole thing stonefaced, Lucky smiled widely, “thought provoking!” The next night he came with his guitar and joined the band, rehearsing and shining in the performance at the shelter. Afterwards, pumped with adrenalin, he hugged me with gusto, “I’m having a blast!” Lucky didn’t show up for the big performance the next night at the Chicago Cultural Center. I saw him at the shelter a few days later: same corner, same vibe. “Shit happens,” he told me.

***

We borrowed the original Living Newspaper device of the “Voice of the Living News,” as a narrator of sorts. It’s so 1930s. How should the voice of the media exist in a twenty-first century Living Newspaper? Can the news be just one voice? And can we tweet in the theatre?

***

SHELTER/CHICAGO had a surprising unintended consequence when I realized that the process itself could serve as a pedagogical roadmap to investigate the news and open civic dialogue. I developed and taught a course for journalism and theatre students to examine original Living Newspaper scripts and their artistic antecedents, investigate and report stories, study traditions of storytelling, and create and perform a public reading of their work, “Surviving the American Dream.” The discovery: The Living News Project process works. And it is replicable without ever being predictable.

***

SHELTER/CHICAGO should be act one with a community dialogue functioning as act two (not a post-play discussion about the work, but a dialogue about homelessness in the city.) In April 2014, we began to see how that could work when SHELTER/CHICAGO became the opening half of a larger event called “Written Off?” sponsored by the Illinois Humanities Council, and the Chicago Coalition for the Homeless, and aired on CAN-TV. How can we follow up on the strands of conversation that night? Was this a “final product”? Where does process give way to product? Does it? Should it? Perhaps this process/product equation doesn’t work for this project?

***

If The Living News Project doesn’t fit notions of “product” and “process” in traditional ways, what will that mean for its future?

***

Three Invitations

If the Living News Project doesn’t fit the mold of an institutional “outreach” or “service” project, how and where can it exist? These ideas for future pathways are open invitations waiting to be answered:

1. Continue the dialogue about homelessness, and make it a national conversation. SHELTER/CHICAGO could be the start of a national network of conversations about the epidemic of homelessness in America. SHELTER/ST. PETE or SHELTER/FLINT next?

2. College residencies. The Living News Project can centralize “the news” in the college experience. Its process and experimental curriculum adds up to an offering for students to engage the news with fresh eyes, using an unsentimental, community-based approach. Was “Surviving the American Dream” the first in a series?

3. New topics. Using the structures and process, should we start developing new scripts? It could be GUNS/CHICAGO next, for example. What about news affecting a smaller city, or a small town? How would The Living News Project work in Portland, Maine? In St. Augustine, Florida?

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here

The Living News is inspiring!

I got great support for this project from 3Arts, an organization that works hard and well to sustain and promote Chicago artists: https://3arts.org