Push-Pull

Available Light and the Fringe Culture in Philadelphia

As a senior at Sarah Lawrence College in 2009, I watched a production of Lucinda Childs’ Radial Courses that had been set on students in the dance department by a member of Childs’ company and was attended by the choreographer (an alumna of the school) herself. The piece, which was first performed in 1976, is a deceptively simple quartet consisting of repeated runs, skips, and hops around a single circle of light. All choreography is set to a rhythm begun audibly by one dancer and kept consistent for the duration of the piece via the footfalls, movement patterns, and sheer determination of the ensemble. Radial Courses is otherwise performed in silence; coordinated changes in direction and sequence occur based on the running count each dancer is keeping in his or her head.

I remember being completely enthralled and not a little bewildered by the feat of mathematical precision and timing playing out in front of me. Radial Courses clocks in at less than fifteen minutes, and the department had organized a discussion with Childs to take place afterwards. Following the talkback was a second showing of the piece, performed by a different cast. The setup of the evening provided a rare opportunity to see inside a process more complicated than most, and gaining comprehension of physical systems that were governing the dance made watching the second performance satisfying in a way that, for me, heady post-performance discussions of concept and meaning rarely do.

For the sake of sanity the viewer needs to let go, at which point it becomes possible to accept and celebrate the larger concept, to be drawn into a benign trance, the same that holds the dancers happily captive.

I was thinking of that day while watching the opening performance of Available Light at the Drexel University Armory in Philadelphia. The production is in the middle of a multi-month, international tour, Philadelphia being only one of three stateside stops. Originally performed in 1983, the fifty-five minute Available Light was created after Childs had begun to actively work with music, a move that can be credited to her collaboration with composer Philip Glass in Robert Wilson’s legendary opera Einstein on the Beach, for which she choreographed and performed the leading role in 1976 before choreographing the entire production in 1984.

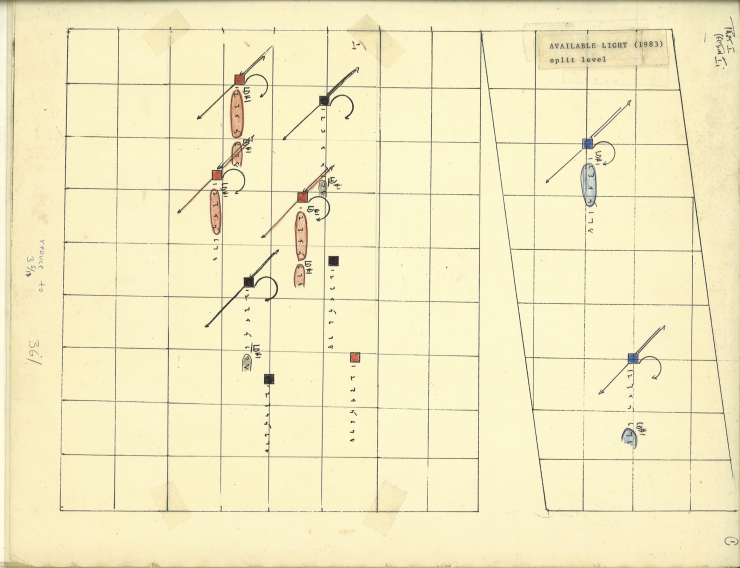

If Radial Courses is a study in precision and an example of a nascent original dance language, Available Light is a masterwork of Childs’ push-pull style—strenuous simplicity, controlled grace—and a display of her work with pattern and sequence at its most evocative. Eleven performers outfitted in black, white, or red (Ronaldus Shamask’s costumes have been given a modern upgrade in the Philadelphia production by Kasia Walicka Maimone—1980s baggy jumpsuits are traded for form-fitting fabric wrapped or tightly draped in diagonals across dancers’ bodies) execute short patterns of leaps, turns, and arabesques. Often sequences begin as unison duets that splinter and ripple through other members of the ensemble, or two dancers do the same combination in opposition, or one performer on ground level is doubled by another on the elevated section of the two-tiered stage. Rarely does anyone move alone, and when they did my heart was in my mouth thinking something had gone wrong. Tugging at a human need to find meaning and create order, the work is almost maddening, and, unlike my experience in college, there was no one to explain the secrets behind its relentless complexity. For the sake of sanity the viewer needs to let go, at which point it becomes possible to accept and celebrate the larger concept, to be drawn into a benign trance, the same that holds the dancers happily captive.

The movement has balletic elements—classically held arms, an overall precision and beauty of line—but with none of ballet’s lushness or sentimentality. There are certainly no masculine or feminine vestiges of romanticism. In a time of (good) sensitivity around issues of gender fluidity and equality, it is exciting to see a piece in which all performers are presented as equal without that equality feeling like a radical or political choice.

Enhancing the choreographic work on all sides is Frank Gehry’s two-story stage, heavy with iron trusses and a chain link backdrop, and John Adams’ hypnotic, synth-filled musical score. Available Light is remarkable for being the collaborative product of a trio before they all became superstars in their respective fields.

Gehry, now a titan in the world of architecture thanks to his sculptural, winged designs for the Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao, the Walt Disney Concert Hall in Los Angeles, and many other works, was less-than revered in design circles early in his career, according to Sydney Pollack’s documentary Sketches of Frank Gehry. Artists, Gehry says, were the only ones responding to his idiosyncratic, anti-establishment impulses. While his swooping aesthetic may at first glance seem at odds with Childs’ mathematical inclinations, it’s easy to forget that the translation of such shapes into concrete and glass takes more forethought and math than most other endeavors. Gehry has always gravitated towards industrial materials—the building blocks of industry and design, just as Childs has dug deep into the pedestrian roots of movement.

“The synthesizer is a very pure instrument; everything it does is technically pure...synthesized sound can be so pure that it very quickly becomes tiresome,” John Adams says of his primary instrument for “Light Over Water,” the piece he was commissioned to create as the soundtrack for Available Light. To texturize the synthetic sounds, Adams added recordings of live brass instruments, an almost-pure tone, but natural and therefore nuanced. The result is at once ambient and dramatic. The dancers have clearly locked into a deeper level of communication with the music; though there are some rhythmic passages, the majority of Childs’ intentional, precise choreography is accompanied by long, broad musical phrases that leave the dancers looking like perfectly in sync magicians.

Gehry has always gravitated towards industrial materials—the building blocks of industry and design, just as Childs has dug deep into the pedestrian roots of movement.

Available Light is one of the productions in the “FringeArts Curated” portion of the Philadelphia Fringe Festival—a series of national and international works happening alongside the open-access fringe event—and as such occupies a unique position in the fabric of the city’s performance scene. No single organization oversees the conduct of the many fringe festivals in the United States and abroad, and no one code defines “fringe” philosophy. Such boundaries would be decidedly “anti-fringe.” Websites like the United States Association of Fringe Festivals and World Fringe highlight the importance of financial accessibility to festivals for artists and audiences, and a general focus on original performance. In a fringe setting, Amy Smith, co-director of Headlong Dance Theater, values work that “asks audience members to do things, pieces that take place outside of a theatrical venue, pieces that don’t live firmly in a traditional genre, pieces that ask questions about the audience-performer relationship.”

As the World Fringe website points out, Fringe festivals have a history of popping up alongside and in response to more institutionalized events. In Philadelphia, where FringeArts now has its own venue and year-round programming under the “fringe” moniker, the organization seems to represent both the establishment and the cutting-edge. Philadelphia artist Megan Bridge makes the interesting point that the proximity of the city to New York creates a culture of competition, which fuels a quest for “excellence” defined by comparison. She told funders that continuing to work with her local dancers after being asked to cast New York and European talent was an “ethical and political stance.” Her grant application was denied.

An automatic hierarchy is formed by having curated and fully funded work alongside a fringe festival bursting with over 1,000 self-produced performances, especially if the line between curated and not is often the line between local and not. Available Light’s powerful impact is not lessened by the fact that it may not fit everyone’s definition of a fringe show. The production’s higher ticket price and traditional setting does not take away its position as a landmark in the history of performance and collaboration, and I for one feel incredibly lucky to have been in the audience. I would be excited, too, to see such attention and care given to finding the next performance luminary within the dynamic ranks of Philadelphia’s local artists.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here