Stealing the Herd

Miss Snooks was really awfully nice

And never wrote a poem

That was not really awfully nice

And fitted to a woman,

She therefore made no enemies

And gave no sad surprises

But went on being awfully nice

And took a lot of prizes.

—Stevie Smith

Stevie Smith’s poem is on my mind this week, because I just had a meeting with a New York producer about a musical for which I wrote book and lyrics. He told me that the lead character was “unlikeable” and “off-putting” and that it was impossible for him to care about what happened to her. Same feedback I got from a Broadway producer, and before that, from a top theater critic in the state where it was workshopped.

in Oliver Twist.

Photo by IMDB.

But enough about me. Let’s talk about male lead characters in musicals—the ones that make big bank. There’s that man with such a hideously deformed face he has to wear a mask. He has an out-of-control sexual obsession with an opera singer, stalking and abducting her. There is a carousel barker who is an alcoholic wife-beater and a thief. Oh, and what about the scam artist whose racket is selling nonexistent band instruments to innocent children? There is the pederastic older man, arguably also a pimp, who trains his band of street urchins in the art of picking pockets. The colonial plantation owner on the lam for committing murder who has fathered a couple of children with his native concubine—who was too much of a social inferior for him to marry. The patriarch who rejects his daughters for marrying without his permission. And, of course, the demonic barber who slits the throats of his customers.

But that’s real life, and this is theater. There is that “willing suspension of disbelief,” which for women in the audience translates into a willingness to believe that these onstage male stalkers, wife-beaters, slashers, etc. are nothing like their real-life counterparts. These men are not dangerous and scary. Well, okay… but scary in a good way. They burst into song, and so do their victims. Whatever the nature of their perpetrations, we understand them to be idiosyncratic dissipations custom-tailored to enhance our fascination and augment our empathy.

Well, you get the picture. No one has ever asked me if I found any of these male characters unlikeable or off-putting—or if I found it impossible to care about what happened to them. In fact, if they had, I would have answered in the negative. Not because I have not known and loved women who have been stalked, battered, pimped, sexually abused as children, exploited by colonialism, rejected by their fathers, and attacked with knives and razors. I have. And I have worked with these women, written for them, lobbied on their/my behalf, and loved them.

But that’s real life, and this is theater. There is that “willing suspension of disbelief,” which for women in the audience translates into a willingness to believe that these onstage male stalkers, wife-beaters, slashers, etc. are nothing like their real-life counterparts. These men are not dangerous and scary. Well, okay… but scary in a good way. They burst into song, and so do their victims. Whatever the nature of their perpetrations, we understand them to be idiosyncratic dissipations custom-tailored to enhance our fascination and augment our empathy. It goes without saying they had terrible childhoods.

Women are smart enough not to spoil our own fun by too literal an interrogation of our responses to these musicals, and only the most paranoid man-hater could read into them sinister ulterior motives.

Well, if throat-slashers and exploiters of children still warrant the patronage of Broadway producers and critics, then what horrendous atrocities has my character committed that have placed her beyond the pale of “likeability?” Fair enough. She cheated against her teammates in the 1932 Olympics. That’s it. Doesn’t beat anybody up, maim, or kill anybody.

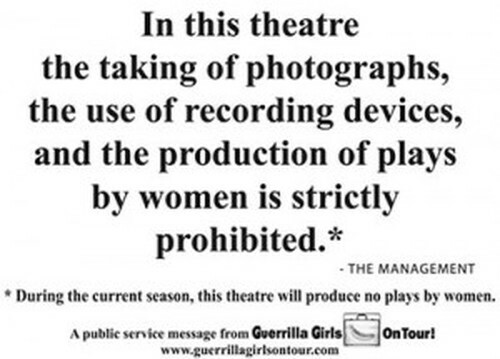

Photo by Pinterest.

It would appear that there exists a significant double standard for what is deemed acceptable behavior for male protagonists and female ones. Could this have some bearing on why women playwrights are so notoriously underrepresented on Broadway, and especially in musical theater?

People come to the theater for spectacle, for something larger than life. These male reprobates are certainly larger than life, and because of this, their narrative arcs can be huge. They are not excoriated for their hubris; it’s the very diving platform for the dramatic plunge we’ve paid to see. These men can be reformed, or they can sink deeper and ever-more-colorfully into the abyss of their depravity. Because of their flaws, criminality, perversions, vices, addictions, dementia, and so on, there can be a sweep to their trajectory and a catharsis or an exorcism for the audience. And when their personal arc meshes gears dramaturgically with the larger historical or sociological arc, such as the Pacific arena in World War II or the French Revolution, the result can be an epic musical.

Photo courtesy of Carolyn Gage.

Plays with female protagonists are handicapped before the pen ever hits the paper. And it’s an ingenious form of discrimination. Nobody is barring the work of female playwrights. In fact, these days, there is a veritable Greek chorus of critics and producers lamenting our lack of representation in commercial theater. They want to help us. They share their wisdom with us when we present them with our work. And that wisdom includes what they know personally and professionally about “likeable” heroines. What they know, and what I am learning, is that “likeable” means feminine. Even if the protagonist is the world’s greatest sharpshooter, she must still throw a match to get her man and take a number that says “I enjoy being a girl.”

What these helpful critics and producers are not critiquing is the implications of their association of likeability with femininity. What happens to the narrative arc, so dramatic with those deeply flawed male characters, when it is applied to a “likeable” female protagonist? She can travel all the way from “likeable” to “more likeable.” Her dramatic arc becomes a dramatic arc-ette, ladylike and petite, like the half-moons of her perfectly manicured nails. One is reminded of Dorothy Parker’s review of Kate Hepburn: “a striking performance that ran the gamut of emotions, from A to B.”

Photo courtesy of Carolyn Gage.

Ironically, in my musical, the unlikeable female lead complains about a similar double standard in the 1930 rules for women’s basketball:

What do I mean? I mean we’re not allowed to play full court, that’s what I mean. Wegotta stop on this center line like it’s a game of “Mother May I” or something. And this business about “travelin’ with the ball?” Three bounces and pass? You don’t see no rule like that in the boys’ game. They get to have the ball as long as they want and go with it as far as they want. Why don’t they come right out with it and tie our shoelaces together? And then people have the nerve to say that girls’ basketball ain’t as interesting to watch, because there ain’t no star players, and that’s ‘cause girls ain’t no athletes. Like to see the boys get to be star players with all that stop-and-start shit.

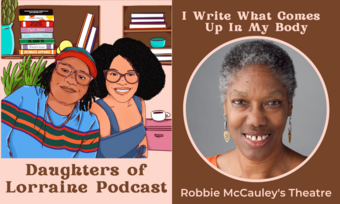

But I haven’t been entirely forthcoming about my musical. The lead character is a butch. There, I said it. And that’s actually why she cheats against her teammates. It’s the 1930s, and these other girls will go on to have husbands and babies, but the working-class butch, with her Adam’s apple and rippling muscles, is facing a lifetime of marginalized spinsterhood and low-paid women’s work… unless she can figure out a way to become the greatest athlete in the world.

And that’s not going to happen by being nice. She is rejected by her mother. She is bullied and ridiculed in high school. She is lesbian-baited by the media. They revoke her amateur status after the Olympics, and they revoke it again when she takes up golf. The catch, of course, is that are no professional sports for women in that era. For my protagonist her choices are clear: “Get tough or die.” She chose to get tough, and that is why I wrote the musical.

I need that kind of role model, because I, too, am up against a boys’ club. I, too, am needing the emergence of a professional producing organization for women to enable our financial and artistic autonomy in a field where dependence on male producers has resulted in our permanent status as amateurs or tokens. I believe that the Disney princesses, for all their multicultural permutations, tell a limited story and one that is largely dependent on magic, coincidence, and luck. I believe there is a powerful untold story in the lives of butch women. It is a story packed with self-determination, analysis and strategy, the identifying of enemies and the locating of allies.

I am coming to understand that it is the power of that story that is what is actually so “off-putting” and “unlikeable.” It is a feral story in a world of sexual colonization. The chorus line of fishnet hose and high heel shoes does not hold up on the same stage with a chorus of butch athletes, dressed to maximize human potential. These are mutually exclusive universes. And when two women end up together, how can we tell which one is the princess… and, even scarier, what are the implications for heterosexual romantic narratives when neither of them are “the girl?” If masculinity can be a normal female attribute, where does that leave men? The lesbian butch strips away the mystique surrounding male power, unveiling the privilege that it masks.

This is how it works. This is how it worked in the sports world in the 1930s and how it works in theater today. You can’t build muscle and worry about femininity at the same time, and being an exceptional individual is not enough to change the game. The game changes when a critical mass of exceptional individuals pool our assets, raising our own money to name our own terms. Until that day, my philosophy is this: as long as they will hang me for stealing a chicken, why shouldn’t I steal a horse? And when I write about the lesbian butch, I take the whole herd.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here