Still Smarting

Women, Shakespeare, and Processing Emotion

A Tuesday night in New York City. An open workshop in a bright white room. A woman finishes her soliloquy and turns to face her audience, expectant for their feedback. One man leans forward, smiling kindly, and begins: “Laura, you’re so smart…” Her heart sinks to her toes. She tries to modulate the look of irritation that sweeps across her face. Because, as she has heard a thousand times, what follows after is that dreadful word: “But.”

A Smart Little Girl with No Heart

Blame it on the Method or on Meisner, but in recent decades, the American approach to acting has been more experiential than intellectual. “Get out of your head, into your space and await the invisible stranger,” as acting teacher and theatre educator Viola Spolin purportedly said. Or as Sanford Meisner advised in his book On Acting: “Act before you think—your instincts are more honest than your thoughts…The text is your greatest enemy.”

What then is a Shakespearean to do? Many actors are drawn to Shakespeare’s rich text and dense metaphors precisely because he challenges the intellect. The Shakespearean actor is attracted to the technical training that verse demands: she studies the minutia of scansion and line endings with the same thrill an opera singer gives to Italian vowel placement. Rosalind’s intellectual landscape is just as intriguing as her emotional one. Indeed, as Stanislavski expressed in Creating A Role, “In the language of an actor, to know is synonymous with to feel.”

Borrowing from the English tradition, Shakespearean actors are encouraged to “speak as fast as they think.” That is, not to draw out a single line of text with masturbatory emotional pauses, such as the Reduced Shakespeare Company famously spoofed in their rendition of “To be or not to be,” but rather to have thought, speech, and the resulting emotion occur simultaneously: the head, as it were, informing the heart. In this case, Shakespearean text is not the enemy; it is the key.

[W]omen still face a gender bias when receiving feedback in the theatre…two out of every five women are subjected to critique that pits their intelligence against their emotional availability. A critique… that is rarely, if ever, levelled at the men.

No wonder then that so many women flock to the Bard’s work! Whether taking on Juliet’s lingual maturity, or Paulina’s biting condemnations, Shakespeare has provided a wealth of roles for women to play. Even his male roles are fair game, when productions open themselves to cross-gender casting, realizing that Cassius or Prospero might be played just as well by a woman, and from a woman’s unique perspective. There’s a reason Sarah Bernhardt could play the Melancholy Dane.

Despite this, women still face a gender bias when receiving feedback in the theatre. Just as Kieran Snyder found in her 2014 article in Fortune Magazine, that women in technology were regularly criticized as “too abrasive” when they expressed an opinion, so in my own experience on both sides of the table, I find approximately two out of every five women are subjected to critique that pits their intelligence against their emotional availability. A critique, it should be noted, that is rarely, if ever, levelled at the men. For example, I had the opportunity to watch two actors, a man and a woman, receive feedback on their exploration of the Dauphin’s speech from King John. The man first approached the piece from a place of caution. He was thanked for his work, and then encouraged to “let loose,” which apparently meant a considerable amount of sound and fury.

When the woman performed the same speech, she approached the piece with an easy confidence, leaning back on her hips, and baiting her scene partner. Immediately, she was told that she was “so smart, but” that she lacked emotional connection and vulnerability. As Isabel Kruse, an Australian actor and director living in New York confided to me afterwards:

In this context, you’re so smart, but…is direct code for, ‘I do not believe you are actually experiencing the level of emotion I deem to be appropriate for the story you are telling.’ When a woman is seen to express intelligently, the immediate presumption is that she is no longer experiencing emotionally, and that is perceived as a divorcement from her experience.

O, I Am Cut to the Brains!

How, then, do women process emotion? Freud was only expressing the historical biases of his time when he declared that women’s mental complaints were due to “hysteria.” Unfortunately, despite advances in the women’s movement, we are still too often subjected to that trope in Western drama. Women are “emotional,” “weak,” and “unfathomable.” Any woman who doesn’t live down to such archetypes may be dismissed as “cold,” “manipulative,” or even “mannish.”

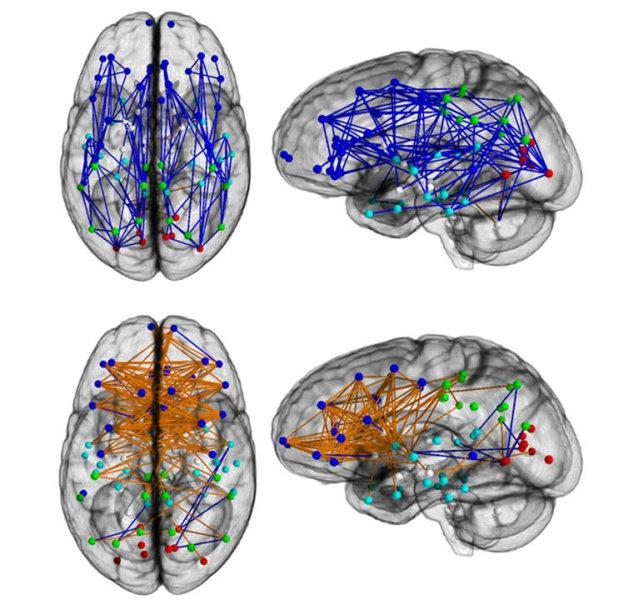

Yet this is not the experience for women from the inside out. Fortunately, recent advances in neuroscience have begun to corroborate what women always knew: that much like a Shakespearean actor, women experience intellect, emotion, and action concurrently. In two studies published in 2015, one from the University of Basel, Switzerland, and another from the University of Montreal, Canada, it was discovered that when exposed to negative stimuli, male and female brains processed that information differently. It should be noted that the subjects of the following studies all identified themselves as male or female. It should be further noted that while these studies seemed to find a difference along cisgender lines, scientists agree that the following discoveries are generally but not definitively true along gender lines. In men, the information was either sent to the dorsomedial prefrontal cortex (dmPFC), the part of the brain associated with decision making, or else was deemed irrelevant and promptly ignored, in what might be called a “fight or flight,” or more accurately, “fix or ditch” pattern.

In women, however, that same negative stimuli was sent primarily to the amygdala, the part of the brain that deals with memories tied to strong emotion. In the experiments, when both sexes were asked to recall what they had seen, it was no surprise then when women were overwhelmingly more capable of recalling images. In the Basel study, where subjects had been shown positive, negative, and neutral images, it was also proved that far from dwelling solely on the negative stimuli, female subjects tended to recall positive images in higher numbers: a fact that may be part of a healthy woman’s coping technique to stress. A coping pattern that is generally called “tend and befriend” among neuroscientists.

Further, a 2013 study from the University of Pennsylvania, discovered that while male brains had greater connectivity within hemispheres (back to front; emotion to action), female brains had greater connectivity across hemispheres (right to left; intuition to intelligence). To put this another way, men tended to react to what was directly in front of them, while women tended to make multiple connections combining various sense memories. For an example of this, look no further than comic Iliza Schlesinger’s brilliant #whatsmymiddlename.

This dichotomy is visible in the speeches of Romeo vs. Juliet. At the point of crisis, Romeo remains fixated on the idea of “banishment,” waxing poetical on the subject for 48 lines, moving immediately from weeping to railing to wishing for death. Compare this with Juliet’s approach to an impossible situation. While we are told, repeatedly, that Romeo is “There on the ground, with his own tears made drunk,” when we finally meet with Juliet, far from the Nurse’s report that her lady is “Blubbering and weeping,” Juliet instead launches into a complicated web of contingency plans. If the Friar’s poison does not work, she has brought a knife. If she wakes too soon, how will she react? Juliet is fearful, yet facing that fear alone. Rather than leaping into action, Juliet asks the completely practical question: “What if this mixture do not work at all?” A line which, when spoken intelligently, is also humorous.

Humor, which it turns out, may be the key coping mechanism for “smart girls” from Verona, Italy to Verona Beach.

The Cold Never Bothered Me, Anyway

Far from praising a woman’s ability to control her actions—even to laugh in the face of strong emotion, Western literature has blamed such “smart” women for being “cold” or “coy,” “calculating,” or “concealing”—when in fact, the word we should attribute to such women is “healthy.”

A 2008 study sponsored by the Pfizer/Society for Women’s Health Research discovered that while men essentially “act first, think later,” women tended to use coping strategies that changed their emotional response to the stressor first, before acting. Because women process negative stimuli through the memory centers, they are at greater risk for anxiety, depression, and PTSD since each cumulative stimulus exacerbates the same part of the mind. Healthy women, therefore, might use positive reframing techniques—such as laughter or changing the narrative—which would then become a habitual response for all subsequent negative situations.

One discussion with a friend, Bernard Brandt, yielded this anecdote:

It has been my fortune to have wed two very smart women. It has also been my misfortune to have watched them both die of cancer. My experience is therefore limited, but my experience has been that smart women seldom break, approach the break with patience and good humor. When they do break, like Rodin's Carytid, they still try to bear the load which is crushing them.

Looking once more to Shakespeare’s women, we find this same quality of humor among his most intelligent heroines. Rosalind all but usurps the Fool’s place in As You Like It, Beatrice can match wits with Benedick in Much Ado About Nothing, and Portia from The Merchant of Venice concocts a practical joke on her lover to test his fidelity. Conversely, Lady Macbeth, no mental slouch, cracks fewer jokes than her husband, until her mind cracks, too.

Why Can’t a Woman Be Like a Man?

Mr. Brandt’s words gives us hope that through time it is possible for men and women to understand each other better. This is particularly encouraging since, according to a 2013 study from the LWL University Hospital in Bochum, Germany, men may legitimately have difficulty discerning a woman’s emotional state without obvious archetypal markers. Ms. Kruse’s analysis of the “You’re so smart, but…” statement acting as code for, “I am having difficulty understanding your emotion” is therefore neurologically spot on.

In the national conversation about diversification and representation, the smart woman’s inner monologue remains largely unheard. And if silenced, then not understood. And if not understood, then dismissed.

Ms. Kruse further notes,

For too many men, feelings aren't valid unless they are visible, and once visible are called hysteria…The woman’s effort to process—literally think through on Shakespearean text—is interpreted as a distancing effort between the woman and her emotional experience, rather than the truthful expression of it.

However, it may also be argued that even though Shakespeare gave us some intelligent heroines, Western drama is woefully lacking the outward expression of a “smart” woman’s inner monologue. Lin-Manuel Miranda’s “Satisfied” from Hamilton may prove of assistance here, since the song energetically breaks down Angelica Schuyler’s emotional calculus as she literally remembers the series of instantaneous decisions that led her to relinquish Alexander Hamilton’s heart.

But Angelica Schuyler’s smart dissection of romance remains a rarity on the stage. In the national conversation about diversification and representation, the smart woman’s inner monologue remains largely unheard. And if silenced, then not understood. And if not understood, then dismissed.

O, For a Muse of Fire!

A Saturday night in New York City. A group of actors gathered in a third floor apartment; a bottle of wine between them, and a new script in blank verse glowing on their iPhones. A woman reads a soliloquy: the Lady of Shallot impatiently waiting atop a battlement. Her language and imagery whirl, as do her thoughts. She speaks of ambition and envy, not with Macbethian melodrama but with humor, pain, and hope.

Since this is a reading, and not an actor’s workshop, the feedback is directed towards the playwright. The question arises: “What, if anything in the script, should not be changed?” Male and female actors universally point to the Lady’s soliloquy. That, keep that. Keep that “smart” someone. But she makes jokes about her own pain, someone points out. That’s because that’s how we think, a woman answers.

Like anything, the archetype of the smart woman requires representation and recognition in order to flourish in the theatre. It requires playwrights—particularly those who write in verse or heightened language—to share their intelligent female protagonist’s inner monologue with all its quirks, distress, grace, and good humor. Similarly, it behooves directors, educators and others to train themselves to recognize how a healthily-minded woman actually interacts with her thoughts, emotions, and actions. And then, rather than steering an actor away from her intellect, to celebrate it. So that when a woman concludes a truthful speech, what she may hear is: “Thank you for being so smart."

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here

Thank you for this article; you have articulated the entirety of my acting conservatory experience. The incessant feedback of "too smart, in your head, thinking to much" has driven me to pursue a PhD in the neurological underpinnings of acting (while still performing). This article helps bring to light the subtle, undermining sexism that I and so many of my actress friends have spoken of and experienced in regards to intellect and emotion; I am so grateful to you for brining the issue to a wider audience!

I love this and will be sharing it widely! It chimes with my personal experience in 'emotional' conversation with men as well as in performance. Thank you!