Summer’s Lease

Shakespeare’s Monopoly on the Magic of Free Outdoor Theatre

A woman in a purple gown made lyrical confessions to the audience from behind a fairy-light strewn rosebush. Her speech was in a language I didn’t know and felt to me at that age (five?) the way Italian opera feels to me now: a swelling in the breast that defies the brain, that forces the mind to quiet. No longer able to sit upright on the picnic blanket, I lay my head in my mother’s lap and drifted off as the play went on without me. I could not say where or when the performance was, nor even for sure if it was Midsummer Night’s Dream (certainly we have seen Midsummer many times while picnicking since), but the moment between sleep and attention remains a vivid childhood memory. The impossibility that the story had come to life in a garden that we had somehow stumbled upon (I was too young to know about PR) enchanted me. I had seen plays before, but there were always tickets, wait times, programs, and rows of seats between me and the actors. Here was a story I could (almost) touch!

This August, as I sat waiting for Commonwealth Shakespeare Company’s Love’s Labour’s Lost to begin, marveling at the art-deco inspired, emerald cathedral and moveable shrubbery Scott Bradley designed to serve as castle/university/forest, a mother led her two daughters—perhaps four and seven—to an unoccupied patch of grass at the front of the stage. It appeared they had not been planning to come, but wanted to see what would happen when the enthusiastic volunteers ended their informational banter and the lights went up. It’s very common to see children at outdoor Shakespeare productions, but it was interesting to consider how many people might have sat down not because they’re Bard-o-files like me, but simply because a free show was about to begin. That anyone could stumble onto such a high quality, vivid, engaging production inspires me to believe that even in this time of ill-advised megamillion dollar sequels (Ben Hur, Jason Bourne, etc.) and bigotry-spewing presidential candidates, art can provide an equal playing field, if only for an hour or two. Democracy and beauty win when “high art” is given away like plucked dandelions to whoever happens by.

Boston could use more opportunities to laugh at its own erudition and scholastic aptitude.

Recently, the poet Douglas Kearney, whose contemporary librettos reach the “common man,” remarked to me that opera was the Las Vegas of its day, and I immediately thought of Shakespeare as a parallel. How strange to think that the popular entertainment of Elizabethan England, where everyday people would jostle at the lip of the stage, eating or tossing apples, finding an un-scrutinized moment to touch a lover, has long been viewed as an elitist cultural marker. The density of the Bard’s poetry has often distanced Americans from the true bawdiness, humor, and palpable humanity so alive in his work. Commonwealth Shakepeare’s long-time, fantastic artistic director, Steven Maler writes, “During Shakespeare’s time, theatre was a part of everyone’s life; but today theatre and the arts in general, can feel unattainable due to soaring ticket prices.”

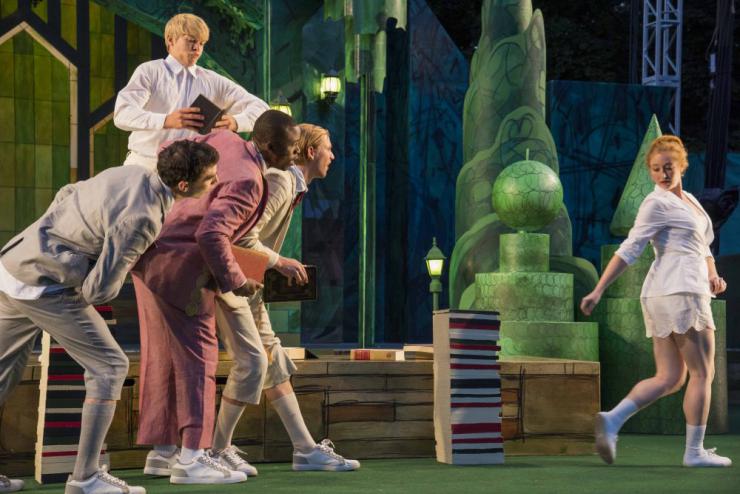

The Commonwealth Shakespeare Company is a beacon of hope that springs up each summer on the beloved Boston Common, reminding us that art is for the people. Maler manages to marry Shakespeare’s complexity with its original crowd pleasing value. Every year, the company delivers a high-energy, visually beautiful, easy to listen to Shakespearean treasure. Each year, the grass teems with Bostonians and tourists excited for the performance (Maler quotes upwards of 75,000 audience members per summer!). This year was no different. I was wowed by the nuance and pizzazz the actors brought—and very glad to see some new faces, including the ferocious, zippy Obehi Janice (Rosaline), the eloquent Jason Bowen (Berowne), and powerhouse Dalton Davis (Longaville). I was impressed by the acrobatic choreography and dynamic blocking: the opening movement piece introduced us to our three princely students, Berowne, Longaville, and Dumain (Nash Hightower) by placing them in a balancing act (literally!) between stacks of tomes and flirtatious female students. This sense of fun and physicality propelled the production. In a later scene, Bowen perched on a pole watching Davis, then Hightower and finally Justin Blancharre (King of Navarre) shoot around the stage until finding an equally precarious hiding spot. Here was Shakespeare with all the pop of a new musical—Hamilton be damned! No one could see this Love’s Labour’s Lost and not enjoy themselves.

Setting the play in a university context, with uniforms, sweater vests, textbooks, and graduation gowns (costumes by Nancy Leary) felt relevant and important in that it poked fun at Boston’s dominant characteristic: academia. Fred Sullivan Jr. as the bombastic Holofernes evinced a love of his own linguistic cleverness that could not but mock many a long-winded teacher. As a city so ruled and inhabited by education, Boston could use more opportunities to laugh at its own erudition and scholastic aptitude, and what better time than summer? The irony of using Shakespeare, considered classical and a bit arcane, to poke fun at the classical and arcane, leant a tongue-in-cheek good humor to the production.

While I am endlessly grateful for the high quality, devoted work the Commonwealth Shakespeare Company produces, I also wonder why Shakespeare monopolizes our summer theatre. Shakespeare and Company out of Lenox, Massachusetts has been performing outdoors every summer for decades, but this season you can see other contemporary works alongside the usual classics (they’re tackling Twelfth Night and The Merchant of Venice); Aphra Behn, a near contemporary of Shakespeare’s, is a focus, with her play Emperor of the Moon and Liz Duffy’s hilarious 1960s meets 1660s Or, about Behn’s life both showing. Many small/community theatres have also taken to producing competing outdoor Midsummer Night’s Dream and Much Ado about Nothing productions. It is so often true that the same plays are chosen season after season in order to fill seats. The theatre scene sometimes feels to me like a collection of cover bands taking turns performing the Top Ten, with Broadway determining what plays in regional Theatres. There’s a natural human tendency to want to follow the leader. With its unbeatable quality, Commonwealth Shakespeare could be thought of as the Broadway of Boston’s outdoor theatre. Theatres must have name recognition in order to make ends meet, but I wonder why when offering a show for free, more theatres don’t try something entirely new and challenging.

'High art' is given away like plucked dandelions to whoever happens by.

It is precisely the electricity of Maler’s Love’s Labours Lost and its derision of stodgy academia that inform my question to the fringe companies and community theatres of the Boston area: if your audience goes to only one production a year, what would you show them? The mother I mentioned earlier disappeared with her children during intermission, leaving me curious about her contact with drama throughout the year. Do we give her Shakespeare because even after four hundred years he is the best we have? As great as he is, I don’t think this can be the only answer. If you were to break the rules of summer theatre, to rebel as Berowne does against the code he swore to, what might you create with, within, for your community?

The Apollinaire Theatre Company performed Lorca’s Blood Wedding by Chelsea’s waterfront in 2015 (in English and Spanish!), and Somerville’s Theatre at First just finished a run of The Spanish Tragedy by Thomas Kid in Tufts Park, but the outdoor performance remains dominated by Shakespeare and by classical work. The magic of Shakespeare’s woods are palpable and unfailing. When the stunning Jennifer Ellis (Princess of France) leads her ladies in a charade at their hideaway in the forest outside of the castle, a fairy tale lives in our own public space. And as performers, we all want our chance to be Titania strolling through a garden on a July night. I certainly don’t want that magic to end or for Shakespeare to stop being performed. And whether the verdant pockets of Massachusetts fill with new works or compete again to have the most original fairies, I look forward to July/August 2017 when once again Commonwealth Shakespeare transforms the Boston Common into a place of magic, community, and generosity.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here