The Business of War Dancing

Exit12 Dance Company’s Aggressed and This is War

This week, HowlRound is partnering with New England Foundation for the Arts in advance of our convening—Art in the Service of Understanding: Bridging Artists, Military, Veterans, and Civilian Communities March 10—12. This convening was inspired by artists who created five new performance works with their collaborators in the military, healthcare and presenter communities, funded by NEFA’s National Dance and Theater Projects. This series asks: How can artists most effectively build relationships of trust as they engage in this work? What do military service members and veterans need to know to encourage them to work with artists? What do artists need to know about trauma in working with military and veterans’ communities?

When consulting with the group of advisors planning our convening, Roman Baca was the artist named most often as a key participant. NEFA is thrilled to have his voice in the conversation, both as a critical thinker and as an important dance maker with an Indigenous voice. —Jane Preston, NEFA

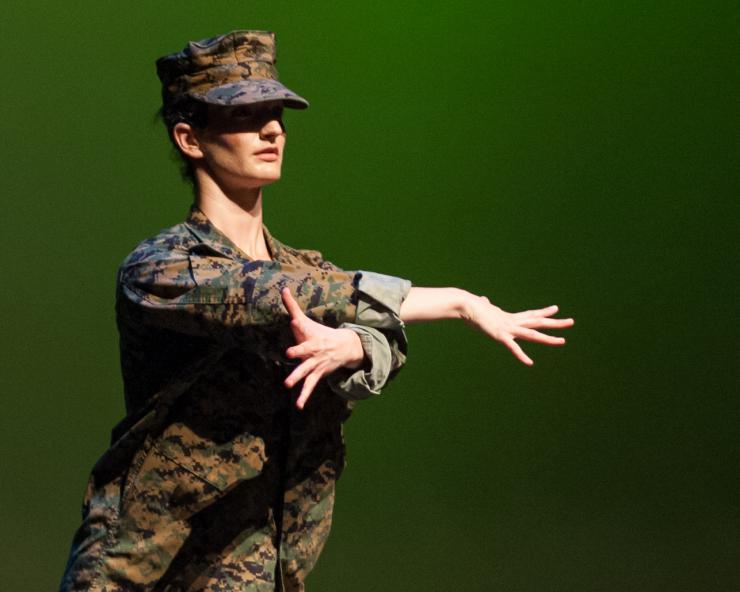

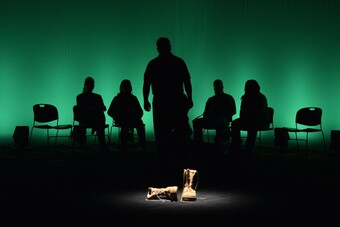

Exit12 Dance Company performed Aggressed and This is War at the Military Experience and the Arts Conference in Lawton, Oklahoma twice in 2015. On the same day, in the same program, back to back, the audience experienced two iterations of the work. It was a spontaneous experiment in order to spark discovery in the power of collaboration. The first iteration was the piece as it stands in the Exit12 repertoire, with the poetry of US Marine Iraq War Veteran William Michael Day, and the music of Raymond Daniel. The work is a physical illustration of Sgt. Day’s struggle with returning home after serving in combat. In Aggressed, the dancer is wearing a camouflage Marine blouse and cover, and is bathed in green light to evoke the color most attributed to combat patrol at night. In This is War, another dancer enters in a black collared, button up shirt covered in red light evoking the removal of the military uniform and the pained struggle of putting a life together post-military.

That night, before the second run of the work, American Indian, Oklahoma Flutist, and Vietnam Veteran Albert Gray Eagle stepped onto the edge of the stage, lifted a simple wooden flute to his lips and began to play. The lights for both Aggressed and This is War turned a soft blue and the dancers repeated their movements to Gray Eagle’s soft and haunting flute-playing.

Indigenous people from all over the globe have used dance for centuries as a way to prepare for battle, to share the burden of war, and to heal from combat.

As the Artistic Director of Exit12, I have pioneered the pairing of dance and war for the post-9/11 generation, but I testify that the unlikely combination is not a new idea. Indigenous people from all over the globe have used dance for centuries as a way to prepare for battle, to share the burden of war, and to heal from combat. In her dissertation on the Eastern Band Cherokee Veterans, Angela D. Ragan notes that the Eagle Tail Dance of the Cherokee was used for building up spirit and energy when danced before a battle during the mid-1700s. The same dance when performed after a battle, was to spread the painful experience of war amongst all the people, and to help the warriors heal. The Navajo War Dance was a war of its own according to Berard Haile in his book on the dance. Performed after combat, it was danced so the warriors could kill the ghosts of their vanquished enemies.

The Aggressed and This is War dances we perform today following the recent wars in Iraq and Afghanistan are performed for similar reasons. It is to share stories of our warriors, through narration and dance, so that audiences can bear a portion of the burden of the experience and carry on the history. It is also to kill the ghosts of enemies. Our generation’s ghosts, however, are the invisible wounds of war and the struggle of reintegration. Ghosts that can be vanquished by bodies moving across space to poems and music.

As I stood off stage watching the dance and listening to Gray Eagle, I was reminded of the decree that the Sioux elders gave Black Elk as they were pursued by the devastating forces of the United States Army in the Black Hills. Black Elk told the elders of a vision he had where the Sioux were no longer a disparate people, but had land to call their own, and enough sustenance to support their families. Instead of just telling the people, in order to give them a hopeful vision of the future, the elders commanded Black Elk to dance it for the people. They knew that it was easy for the people to see the pain and despair that lay in front of them. What wasn’t easy to see was the way beyond the darkness.

In a theatre in Lawton, Oklahoma, with a small wood flute, Albert Gray Eagle transformed a dance of anguish into a dance of hope. In doing so, he, the dancers, and the audience resurrected a timeworn ritual of sharing stories of war through narration, music, and dance—to provide a vision of the future that can heal the world.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here