Theatre History Episode # 32

Seret Scott Looks Back on the Free Southern Theater

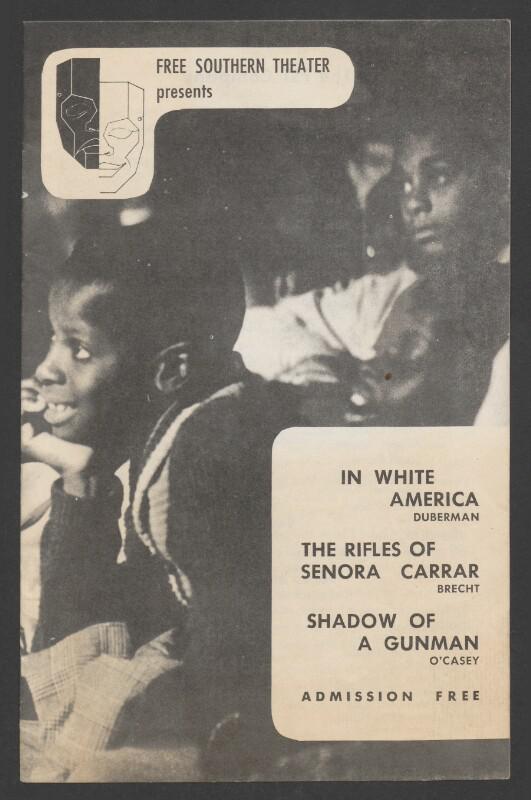

The Free Southern Theater was one of the most important activist theatres in the United States, bringing politically- and socially-engaged theatre to poor African American communities in the South throughout the 1960s and 1970s. One of the performers who joined the Theater was Seret Scott, who went on to play key roles on Broadway in My Sister, My Sister and for colored girls who have considered suicide/when the rainbow is enuf. Her memories of engaging with the Free Southern Theater’s audiences offer new suggestions for how theatre activists can engage with the economically-disadvantaged and politically-marginalized.

From the Judy Richardson Papers at Duke University Libraries.

Links:

- Learn more about the Free Southern Theater.

- Read Michael Moore’s 2013 HowlRound essay reflecting on the legacy of the Free Southern Theater.

- Find out more about Seret’s career on and Off-Broadway, as well as her work as a director.

You can subscribe to this series via Apple iTunes, Google Play Music, or RSS Feed or just click on the link below to listen:

Transcript:

Michael Lueger: The Theatre History Podcast is supported by HowlRound, a knowledge commons by and for the theatre community. It's available on iTunes and HowlRound.com.

Hi, and welcome to the Theatre History Podcast. I'm Mike Lueger. Theatre has long been a tool for those working to bring about social and political change and one important example from recent American History is the Free Southern Theater. Today we're speaking with Seret Scott a veteran of the Free Southern Theater. Her acting career has included roles in the Broadway productions of My Sister, My Sister and For Colored Girls Who Have Considered Suicide/When the Rainbow Was Enuf. Since 1991, she's been exclusively writing and directing. Seret thank you so much for joining us.

Seret Scott: It's my pleasure, thank you.

Michael: Can you tell us what the Free Southern Theater was? What was its purpose?

Seret: The purpose of the Free Southern Theater at that time, was to articulate and acknowledge the experiences of southern African Americans who- from this point on I'll say Black Americans, because that's what we were calling ourselves at the time. It was to make them aware of what was actually going on in the government and with policy, with laws, with anything that had to do with education, anything that had to do with. That they were being left out of that kind of system and systematically left out of that. The Free Southern Theater was a tool, a creative tool, to teach the people that we performed for about what it is or what it is that they are expected to have as American citizens and were denied in some way. So, sometimes we did scripted plays, sometimes we did improvisations. Actually, more actually we did improvisations based on whatever the politics of that particular community happened to be.

And what I mean by that is if we got into a small rural community in Mississippi that had been ongoing boycott of the white stores downtown, because either they wouldn't serve blacks or they would do certain things like make you stand there while they served all the white customers. No matter how long you had been there and when someone else walked in the door. So, what we would do is go in and do an improvisations based on your right and what it is that you can expect to have happen. Sometimes, we were able to express those things through communicating with them, with when I say them I'm talking about our audiences, in just talkback or whatever. I hate to use the word talkback, because that wasn't exactly the way it happened. But most of the time it was through this sort of creative way of doing things and that would be the improvisations and plays and all.

And we worked not so much in theatres, as a matter of fact, I don't remember actually playing a theatre even a small grass roots theatre. We worked mostly in churches, backyards, parking lots, cotton fields on the edge of dirt roads. We'd just set up our equipment and do an improvisation about something going on in that community. And our audiences were mostly sharecroppers and tenant farmers, migrants and all when we were in those rural communities, but every now and then we'd do something right in New Orleans where the theatre was actually based. And we had a little small space there and sometimes we could do something on a university campus in one of their small theatres.

Michael: This sounds... I can't imagine what this experience must have been like. But, it sounds intense in terms of the amount of travel; you mention the number of different scripted and improvised works that you're performing. What was this experience like for you personally?

Seret: For me, to put it in perspective, Dr. King was assassinated in April 1968 as everybody knows and I was at NYU at that time and it was pretty difficult for me after his assassination. Now, one of the things that happened just serendipitous was that Gilbert Moses, who was one of the original founders of the Free Southern Theater happened to be at NYU in the School of Arts with me at that time. He was a grad student, I was a freshman undergrad or something. And he had already established the Free Southern Theater, it had some political difficulties right within itself. Meaning, not everyone was on board about how the Free Southern should have operated at that time. So, it dissolved for a brief period and that was the period when he, Gilbert, came to NYU to come to school and I met him and when Dr. King was killed he said he was going back to reestablish the Free Southern. And I said I absolutely wanted to go down to do that with him and the rest of the organizations that had come together in a bit of a way of trying to figure out what to do next.

So, I did, I went down in January of 1969. I was a young, young person and just out of school, like I said the university. And I didn't know much about anything, meaning I understood that there were things happening in the south. It was on the news, that was one of the incredible things about the sixties, seventies, that everything that was happening in the Civil Rights Movement pretty much you saw on the news that night. Everything that was happening in Vietnam you saw on the news as well, so there was no real blackout. You kind of knew what was happening and when I got there. When you're young it's all gonna be all right. You have no fear of anything, so that was kind of what was going on with me. But, I quickly began to understand how much I did not know. Meaning, I met nine year olds who grew up in Mississippi or Louisiana, which are the two states we mostly concentrated on. And they understood things that I just never had to understand. I mean, they knew how to move through their society in a way that did not put them at risk. I could go further on that; just moving from one place to another without being hurt or ... it was always that possibility down there at the time.

I have to say that because I had left a college, a university, to go south did not necessarily mean that I was accepted by the people that we were working with. One of the things that is really important to put on the table is that I remember one of my specific experiences. This is in a really rural part of Mississippi, we were setting up to do the show or improve and people for real sometimes we would call -there were all kinds of names for us, because many of the people had never seen television. Can you believe that? They had never seen television, much less a live performance. The best that live performance would have been would have been in the church or something or a speech from some civil rights person that was outdoors. So, they didn't quite have a word for us. An actor did not enter the world for them.

But, I remember one day we were setting up. And setting up simply meant that we had a couple of platforms- I think there were three platforms, actually. They were six or eight inches tall and I don't know maybe four to six feet long and we would put them up anywhere in the cotton fields. And we sometimes had lights and sometimes we didn't.

But, these young girls were standing there looking at me and talking to me, because I was to many of them I looked much the same as they did in terms of how old I was. And they were talking to me about New York and about Washington DC, which is where I'm originally from. And they were just asking questions and I mentioned I had been at the university in New York and that I had left to come down to work with the group and to work with people like them. And there was a silence and one young girl said, "You left a college to come down here and be with us to do this? I would do anything to be able to go to school." And she was about eleven, she was maybe between eleven and thirteen and she had maybe a second grade education, because she was working in the cotton fields or the any kind of crop fields or even tobacco fields almost all the time. She was the daughter of probably a sharecropper. And it just sort of struck home that whatever I thought I was doing that is exactly what they wanted to be doing and that is to go to school.

Michael: It strikes me that apart from the social and political backdrop to all that you and the Free Southern Theater were doing, there's also this, from what you're describing, there's also this process of building bridges between your world, as you mentioned, leaving NYU, coming down and speaking with these young working who are working in the cotton fields. How did audiences respond to your performances and do you think it affected them in a particular way?

Seret: First of all, we were presenting information to them that they were perhaps getting from some of the civil rights workers that were passing through. But, for the most part they were not getting in a way, maybe, that they quite understood. The audiences would, especially when we were performing outside in some setup venue like in a parking lot or whatever, they would either sit on the ground or stand around. Our shows, if you want to call them that, weren't very long. And they would stand or sit on the ground or sit on something like a crate or basket or something that was around. And they would watch in a way that did not give us any idea of what they feeling or thinking. They would just sort of watch. And every now and then they would just speak back or do something that let you know they were actually very engaged.

I remember I was doing, one of the pieces I was doing, was a two character play that was written by Gilbert and I was playing an old, old lady and my husband was an old, old man and we'd been sharecroppers and/or migrants all our lives. And I was berating him in the play about never having taken a stand and that was what the piece was about. It was short and during the whole time of the play, or at least several pages of it, I am supposed to be opening a jar. And I'm so busy berating my husband that I don't get the jar open and I'm just squirming and trying to get this jar open. And then the nicest gentleman of about, I don't know, sixty five with bib overalls on and all who was sitting there. He just got up and he walked right up on the platform and he took the jar, and of course, the top wasn't on hard or anything or tight it was just part of the play. But anyway, he took the jar and he opened it and he handed it back to me and he said, "Oh, it wasn't even on that tight." And then he sat back down and waited for the, whatever we were, to start again and nobody in the audience though anything different.

It wasn't like people said, "Oh, you can't walk up on stage." It was fine I couldn't get the jar open and we were performing something, so you just go in and you help out the person who's up there doing it. And that happened often where they would just come up on stage and pick up a prop or stand there and look out. And just because they didn't have any problems with that or anything and we were very used to it. It was actually kind of wonderful. I guess you call it interactive today.

Michael: Sounds like this is such an important experience and after your work with Free Southern Theater you go on to prominent Broadway productions, writing and directing as I mentioned in the intro. But, I'm curious how this experience stayed with you, how it influenced you both personally and in terms of your art, your professional career.

Seret: In terms of influencing me, I don't know that I ever left that Free Southern experience. I always found my way back to theatre that I thought was political, that was activist, that made you have to think or put something else in your thought process. That gave you a different way of looking at whatever was going on and a different way of dealing with it. So, it wasn't always just one on one or some sort of conversation that creatively there was some other way of working on anything that you wanted to say to express.

And, especially after the Free Southern Theater when I got back, one of the things that happened was one of the plays we did down there- Slave Ship, which was written by then Leroi Jones, was a huge hit down there even though it was almost no money involved and it was a limited sort of way of doing the whole thing. The theatre company called Chelsea Theater Center at Brooklyn Academy of Music, somebody from that went down and saw the show, and brought that show up and of course they did a professional job of producing it. So, I did that and that show went on to Europe and it was a huge, huge event to put the Free Southern Theater on the map. But, after that when we came back, I got involved with a lot of things like, anti Vietnam protest theatre, prison theatre going in to Sing Sing and Standford Hill and Rikers doing plays that gape inmates in different way of looking at what was going on in their lives.

I was involved with marches and that was just part of what it was that I felt most comfortable with. But, at the same time, because I had been at a university and all, I did do straight professional Off- Broadway plays. And My Sister, My Sister, which is what I mentioned earlier, was a play that started at Hartford Stage and then moved in and eventually was on Broadway. It was the story of a young child, young girl who was mentally and sexually abused. And it was the first time mental health issues had been dealt with in theatre when it came to black children. So, it was a huge, for me, it gave me a lot of exposure. Which meant that I was able to work on all kinds of other projects, professional projects after that, because I was the young girl in My Sister, My Sister. And I think I did For Colored Girls on Broadway shortly after that. And since then I did act for a long period of time, maybe twenty years, I don't know. Then there's directing, sort of happened kind of out of the blue, and I became very much involved with in and that's what I've been doing exclusively for about twenty five, twenty six years now.

Michael: Moving a bit beyond your own personal, professional achievements, I wonder looking back on your experience. Do you have any conclusions that you drew about activist theatre more generally, what it needs to do, how it needs to relate to its audience? Any sort of lessons that you would impart from your time with the Free Southern Theater?

Seret: Yes, I guess I do. I don't know that I gave it that kind of thought, but I find that activism now sometimes has been polished. And has been given a stamp of approval and I don't know that it allows the people that are doing the work, and the people watching, it allows them to understand how far something can go to make some changes. So, street theatre back then what we would call happenings and what now you call them flash mobs and all when things just start to happen. But, the flash mobs I'm finding, and perhaps it's not always that way, but they're always about something social if someone's like, "Let everybody get together, because I'm gonna ask my girlfriend to marry me." And you have this flash mob thing happen and all.

Whereas, I remember doing much street theatre where we would actually get out there and set up something right there on the street corner and really attack a problem or attack something that was in the mail, in the news. And, I don't find that happening anymore partly because I think there's more of a crackdown on that sort of thing. You get too many people, a public assembly, I guess is what I'm saying, and you get too many people and the police move you along. Also, it's much more dangerous now- it's interesting, it's more dangerous now that people may decide they don't like what they're hearing and people will shoot you. Where that wasn't necessarily happening in the sixties and seventies when we were on the street doing this sort of thing.

And I think there's so much disagreement about what people actually believe in or want to support. The country pretty much rallied around the anti-war protest of Vietnam for a whole lot of reasons. You had the people who were going to war and who were drafted and all, but then you had this tremendous amount of people against the war. And also, it was a draft war, which made it even worse, because young people had no choice. Young men had no choice about things. We were kind of able to find our audience.

Now, I almost...I didn't do it, but I almost went down to Occupy Wall Street, because that's kind of my thing. But, the thing that happened with Occupy Wall Street, for me, was I never knew what message to take away from that. From what they were doing. There were too many messages. And, at least, again, from my point of view, there were too many messages. And, I think that's why they weren't able to sustain themselves that well.

Activists Theatre nowadays has to be driven by people who almost have no other agenda. And the reason why is because it is so involved. Not that we weren't having those same things at that time, but now will all kinds of social media things get to be so far to one side or the other. So, you have Black Lives Matter and I can read about what they're doing on the one hand and then I can read why other people say this is a terrible group or terrible organization. And you didn't quite have that much knowledge, back and forth knowledge, back in the day as they say. So, you find things that are not- you made up your mind and you were able to go on and act on that. And nowadays, it just leaves people in the middle. I think that Black Lives Matter has great potential. I don't know that just active protest in the streets of just marching and or, I don't know that is actually moving the effort and the ideas as far as they need to go.

I do think some sort of creative influence, which I'm finding is happening more and more, would be very helpful for getting the attention they need from more than people who just see it as a single protest or this is what these people are yelling and screaming about. And I think that theatre and art and music and all can do that. It seems like that's moving more in that direction.

Michael Lueger: We'll post additional information about the Free Southern Theater as well as additional information about Seret in the show notes. Seret, thank you so much for joining us.

Seret: Thank you. I hope I said things that illuminate the Free Southern and how I can look up Activist Theater.

Michael Lueger: If you'd like to continue today's conversation, please visit HowlRound.com and follow HowlRound and @theaterhistory on Twitter. A big thank you to the staff at HowlRound who make this show possible. Our theme music is The Black Crook Gallop, which comes to us courtesy of the New York Public Library Libretto project and Adam Roberts. Thanks as well to Tim Crest who designed our logo. And finally, thank you for listening.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here