Theatre History Podcast # 16

Exploring the Surprising—and Disturbing—Origins of “Jingle Bells” with Kyna Hamill

We all know the classic Christmas song “Jingle Bells” —or at least we think that we do. Dr. Kyna Hamill of Boston University has been looking into the origins of this beloved holiday classic, and what she’s discovered about its creator and its first known public performance may cause us to look at the song in a rather different light.

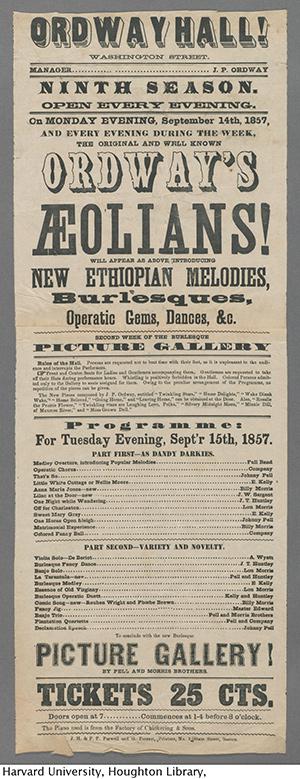

included "One Horse Open Sleigh," the song that we've come to

know as "Jingle Bells." Image via Harvard University's Houghton

Library, Harvard Theatre Collection, American Minstrel Show

Collection.

You can subscribe to this series via Apple iTunes, Google Play Music, or RSS Feed or just click on the link below to listen:

(An old recording of Jingle Bells plays)

Man: Hello, there! There comes the sleigh. Whoa ho, now Bonaparte,You could hang your hat on it there, darling. Say, Mabel, where is that lunch basket?

Mabel: Why, I think I'm sitting on it!

Man: Oh, you think you're sitting on it, do you? Well you know you're sitting on it.

Mabel: Yeah, you put that lunch basket under of the seat, will you?

Man: Now, driver, I want you to stop at the very first road house you come to, understand?

Driver: Very good.

(Old Recording of Jingle Bells ends)

Michael Lueger: Hi. Welcome to the Theatre History Podcast. It's December and we're talking about a well-known holiday classic, "Jingle Bells", but the story behind the song isn't quite what you might expect. Our guest today is Dr. Kyna Hamill. She's a senior lecturer at Boston University and the editor of They Fight, classical to contemporary stage fight seats. Kyna, thank you so much for joining us.

Dr. Kyna Hamill: Hi, Michael.

Michael: How did you get into the history of the song "Jingle Bells", and what has the research process been?

Kyna: I've worn a couple of hats while doing research on this. It really started by me being a volunteer at our local historical society. I live in Medford. Every Sunday I'm a reference researcher and I help people who have questions about anything to do with Medford history. Every Christmas, every December, we very often got a phone call from a media outlet who were interested in the story of "Jingle Bells".

If you go to High Street on Medford, there's a plaque that makes that claim that "Jingle Bells" was written there in 1850, but the thing is that Savannah, Georgia has a very similar plaque that makes the same claims. It sort of became a media story. People really interested in this division, where was it written? Where was it written? Every Christmas—and I can go back to about 1984 in the records—the story gets rehashed almost yearly to the point that the mayors of Medford and Savannah were writing some pretty angry letters to each other. We have all of those in the vertical files of the Historical Society.

I have done a couple of media interviews about it. I am now apologetic to some of the information I gave, because it was based on what was in the vertical file. I'm a theatre historian. I went to Tufts to the Tufts PhD program. The nineteenth century was not really my field so I started to get back to some of my roots from classes I took at Tufts. My area is really the seventeenth century. I started to look at asking a different question, not where was it written, but where might have it first been performed. That was a much more fruitful question and that is what led me to some new discoveries about the song.

Michael: Let's talk about the song itself. You—In some early articles it's been characterized as the Thanksgiving drinking song about drag racing which is not exactly how we tend to think of "Jingle Bells." Is that true? What's the story behind the actual content of this holiday classic?

Kyna: Okay, so in the vertical file, we have a lot of articles from past stories that have been done that claim that it was Medford, that claim that it was based on sleigh riding songs—Excuse me, sleigh riding races that were done in Medford along Salem Street. Anybody who's local would know where that might've been. I went through the news clippings and just tried correlate all the different points that seemed realistic. That's usually the way that I answered the question. I'm realizing the error in that because a lot of them were media stories. It was all seasonal.

What I most realized was the sentimentality that's associated with the song, both from Medford and Savannah. The Thanksgiving drunken sleigh ride songs was an article that somebody wrote. A couple other people picked up on it. It's very possible that it became that but that's not how it was first performed. I think that part of the interesting thing about the historiography of this song is how it's been recycled as a seasonal story and it's really kind of biased the historiography of the song be becoming a sentimental, kind of romanticized story in local history. Both Savannah and Medford have done that and now I'm learning it's even possible that Troy, New York has done that because the writer also lived there as well.

Michael: Can we talk about the writer, James Lord Pierpont, bit of a character.

Kyna: James Lord Pierpont was born in Boston in 1822. He was the fifth of six children. He was the fifth son of Reverend John Pierpont Sr. John Pierpont Sr. is himself a really interesting figure. He's actually the grandfather of JP Morgan, as in the banking magnet. Therefore that places James Lord Pierpont as the uncle of JP Morgan. Just to step aside and say that a lot of the papers that I looked at were at the Morgan Museum in New York. That was really helpful, a lot of letters between James and his father, a lot of letters between James and his brother and other people as well.

He is an interesting figure. He was born in Boston. He did live in Medford. He did live in Troy. He did live in Savannah, and went back and forth between them. He can also be found in Florida. He lived out the rest of his life in Florida. He can be found in San Francisco during the Gold Rush and actually during some of the San Francisco fires.

He's just, to me, a really fascinating figure who represents a nineteenth century man who grew up in the north in the United states, eventually ends up down in Savannah married to the daughter of the mayor of Savannah, and ends up fighting for the confederate cause and ends up pretty much fighting on the other side of where his father was in terms of the war.

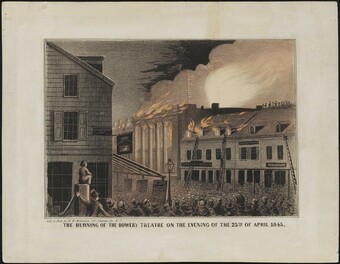

In the meantime, he's always looking for work. I've got him down with quite a few different professions. Sometimes he'd last two weeks at a job and he'd have to start something else. As a composer, you can trace about twelve songs that's written by him, all of them minstrel music at minstrel halls in New York but especially at this particular minstrel hall in Boston called Ordway Hall which operated from about 1850 to 1858 on Washington Street.

Michael: Yes, and this is one of the interesting things that pops up early on in your research, it seems, this debate over where and when Pierpont wrote the song. As you mentioned, it eventually led you to studying minstrel shows in the 1850. What was the original theory about when and where this was written? Then perhaps having answered that, what did you find out about where it was actually first performed?

Kyna: The question of where it was first performed brings us to a particular tavern in Medford. He apparently found a piano and wrote out a merry little ditty. It sounded very happy. That's where it was written.

Savannah makes the claim that it was probably written during this time as an organist for the church that his brother was minister of down in Savannah. These are dead parts. They don't really go anywhere. It's either Savannah or it's Medford, but it can't be both.

As I said, I asked a different question. I asked where was it first performed. It really was not that hard. I looked at the sheet music, which was published. The first time it was published was 1857. It's published as "One Horse Open Sleigh." The sheet music is dedicated to a man named John Ordway. John Ordway ran this minstrel music hall on Boston on Washington Street. In the old Products house there's a plaque there as well very close to the CBS there. You can go down and see the plaque.

This minstrel hall actually premiered a number of James' songs beginning in 1852. He's well known to have written a number of minstrel songs, but for some reason the "Jingle Bells" song, it was re-copyrighted in 1859 as "Jingle Bells, or the One Horse Open Sleigh", has really slipped through the cracks of it being part of the minstrel tradition. I think it's part of this romanticized history of the song. For example, in 1946, there's an article that comes out in the Boston Globe. The Boston Globe Archives has this. It's really the first time that somebody makes the claim that James Pierpont wrote the song and James Pierpont came from Medford.

The thing is that he's associated with writing in the Steven Foster tradition. That's a really nice way of saying that he's writing blackface minstrel songs. Even though he writes all these other songs, Jingle Bells does not get put in the category of being a minstrel song, so it seems really obvious that this song might have been in that tradition. It didn't take long before the fantastic Harvard Theatre Collection, which has digitized all of their minstrel music and minstrel playbill collection- I went there and I went online.

In 1857, two days before the song was copyrighted, there it is. "One Horse Open Sleigh" being performed September 14 or 15, 1857 and along with another song, "The White Cottage," that he also wrote. That makes two of his songs were being performed. Now, that's the earliest I found it being performed. I don't see it any other sources. I have never been able to find it in any other hall, any other place.

I think because Ordway supported James' songwriting career—as I said he started doing music there in 1852—it's very natural that that might've been the very first performance of this song. It continued to be performed throughout the season and then eventually you can find it showing up in New York and Philadelphia, and then it eventually makes its way to song anthologies. That's the first performance of "Jingle Bells."

Michael: I wonder if you could maybe explain a little bit more about the song works in the context of a minstrel show. Like you said, this is originally seen as being in the line of Steven Foster or closely associated with minstrel shows. I think for many of us, it might be a little surprising to hear that a performance style that we have some pretty negative associations with, understandably, would feature a song like Jingle Bells.

Kyna: Again, I think there's all these reasons why this song has slipped through the cracks of its historiography in the minstrel catalog. It doesn't have what Eric Lott's great book, Love and Theft, talks about, this dialect. It doesn't have a lot of words that imply racialized dialect, but it was listed on the playbill as being under the dandy darky section of that evening performance.

It may not have this racialized dialect but there's a lot of lines that have a legacy that are associated with his legacy of minstrel. For example, the performer that did it, his name was Johnny Powell, originally from New York and made its way to Boston in 1854. He was known for singing a song called "The Laughing Darky", again, another very stereotyped racialized way of depicting blacks, that white men in blackface would do, "The Laughing Darky."

Let's just way that in a line like dashing through the snow, in a one-horse open sleigh, over the fields we go, laughing all the way, ha ha ha. Imagine that you have a character like Johnny Powell, known for singing his song called the "The Laughing Darky," is reading a line like that. For an audience who went regularly to the minstrel songs, to the minstrel theatre, to see him perform a line like that would have perhaps just made reference to his own catalog of songs.

There's a number of situations like that throughout the song. I think there's a line. A day or two ago, this is first three. We don't sing these verses very much. A day or two ago, the story I must tell, I went out on the snow, and on my back I feel. A gent was riding by in a one horse open sleigh. He laughed as there I sprawling lie but quickly drove away.

Again, imagine a white man in blackface performing a racialized dandy and singing a song about somebody coming up to them and then not helping them in the snow. I might be reading a little bit into this, but I don't think so. I think this is where you have to put on the theatre history hat and think about the say that it would've been performed, the person who performed it, and the catalog of music that that person regularly sang in that same music hall.

Michael: Another aspect of this that you pointed out in a couple of interviews that you've given is the fact that the song is a pretty commercial proposition. It sure bears some similarities to other contemporary songs and obviously it's something written for performance. It's something that earns Pierpont some money.

Kyna: Yes, so as I mentioned, Pierpont is always out of work. He's pretty creative in the way that he comes up with work. His letters speak of him doing all kinds of things, from making dresses to running a shop in San Francisco to working at a dairy. It goes on and on and on, all the different things that he did. I think that making songs with Ordway at Ordway Hall, there were a couple of songs that were already in the catalog before 1857, a song called "The Merry Sleigh Ride", which was sometimes written as "De Darky Sleigh Ride Party."

Again, a racialized dialect and this has a jingle chorus which goes something like jingle, jingle, clear the way, tis the merry, merry sleigh. Listen to my song as we play along. A lot of these sleighing songs are singing about sleighing, singing about singing about sleighing, and perhaps inviting people to sing along.

Now, I'm not entirely sure about that because Ordway Hall was quite a conservative performance hall. He actually lists in the playbills don’t stamp your feet, so I'm not entirely sure whether people were singing along but the performer was singing about singing about sleigh songs. A number of the sleigh songs were like that. There was one called the "Buckley Sleighing Song," which also has a jingle chorus. There's a number of them that you could find.

In 1957 when "One Horse Open Sleigh/Jingle Bells" comes out, it features the same narrative. You've got let's go out and sleigh. Let's sing about doing it. Let's get some pretty girl. It might be an upset. Then there's the jingle chorus that goes along with it. He's capitalizing on what I say is sleigh song for having a moment in the middle of the nineteenth century, especially in the northern cities of Boston, New York, and you can find it in Philadelphia as well, all of them in minstrel halls.

Michael: How do you we arrive at the version of "Jingle Bells" that we know today, or perhaps how do we put it into the context that we now associate it with today?

Kyna: It shows up in a number of college parlor and parlor anthologies. These are anthologies that borrow from parlor music but also the minstrel tradition, just songs that have good tunes that glee clubs and all kinds of different people interested in piano music and parlor music would put together. It can be found in the 1880s in these kinds of anthologies. Until recently, I couldn't really find what happened to the song between the middle of the nineteenth century and these parlor anthologies.

I've actually recently been given a collection of playbills from boy's choirs, some Catholic boy's choirs that were performing all over Boston in the 1860s, and they're singing "One Horse Open Sleigh." It's certainly being performed pretty regularly. I don't think these boys would have been doing it in blackface so therefore, it's a popular enough song that it's being performed in various different amateur and professional contexts.

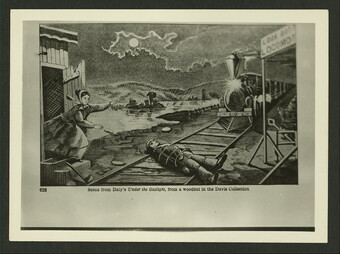

By the time it makes it to the anthologies in the 1880s, and especially at the turn of the century, when you have the Edison Quartet performing it and recording it for the first time, it's really starting to move slowly away from the minstrel tradition, as many of the songs did and slowly make its way into a much more tradition around the holidays. By the time we get to the 1920s it's pretty rooted, and you can see this individual cultural as well. It's rooted in the tradition of the Currier and Ives of the happy sleighing couples that are sleighing through the snow, and in a very romanticized way.

I have a lot more research to do to really figure out at what point does it become the Christmas song that it does. I think that's really mid twentieth century, but there's a really interesting—It's interesting to trace the path how this music gets parities and transformed into this minstrel tradition, into a Christmas tradition.

Michael: I should not that you've got a peer reviewed article coming out in theatre survey in 2017. In terms of this scholarly conclusion, you do have one of those coming up within the next few months. Yes?

Kyna: I do and what I try to do in the article is give a context to the sleighing as an activity, sleighing as an activity that therefore becomes sleighing as a topic in music, as a topic in stories, and in poetry, and then looking at how the visual culture follows this tradition of sleighing. I particularly visual culture that follows slaves who come from the south and come into the north and place them in the context of winter sports and winter activities and start to burlesque basically black bodies in the snow, which in some ways I think is a part of the tradition of the black- It comes from the tradition of the minstrel shows.

It's a complicated history and I had to look from the article. It was way too long. There's still so much to be said. I think it's just so important to put it into context, to put the minstrel tradition into context. To put it in context not just as a theatrical tradition but for example, in Boston specially where Ordway Hall, how Ordway Hall was situated as a middle class entertainment for factory workers and immigrants, and how blacks were actually allowed to go to these performers until 1858, when all of a sudden they weren't. There's just so much to say and put into context around the song, that I think it's been really interesting.

Michael: We'll host some visual links and show notes to material from the Harvard Theatre Collection related to minstrel shows, some other material about Kyna's research on "Jingle Bells", and a link to that recording that she mentioned, "Sleigh Ride Party", the first known recording of what we've now come to know as "Jingle Bells." Kyna, thank you so much.

Kyna: Thanks, Michael. Thanks for taking the time.

Michael: If you'd like to continue today's conversation, please visit HowlRound dot come and follow HowlRound and At Theatre History on Twitter. A big thank you to the staff at HowlRound to make this show possible. Our theme music is the Black Crook Gallant, which comes to us courtesy of the New York Public Library Libretto Project and Adam Roberts. Thanks as well to Tim Cress who designed our logo, and finally thank you for listening.

(Old Recording of Jingle Bells plays again)

Mabel: Good night, Johnny. I've had a lovely time.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here