Theatre History Podcast #52

Remembering Argentina’s Traumatic Past Through Theatre with Dr. Noe Montez

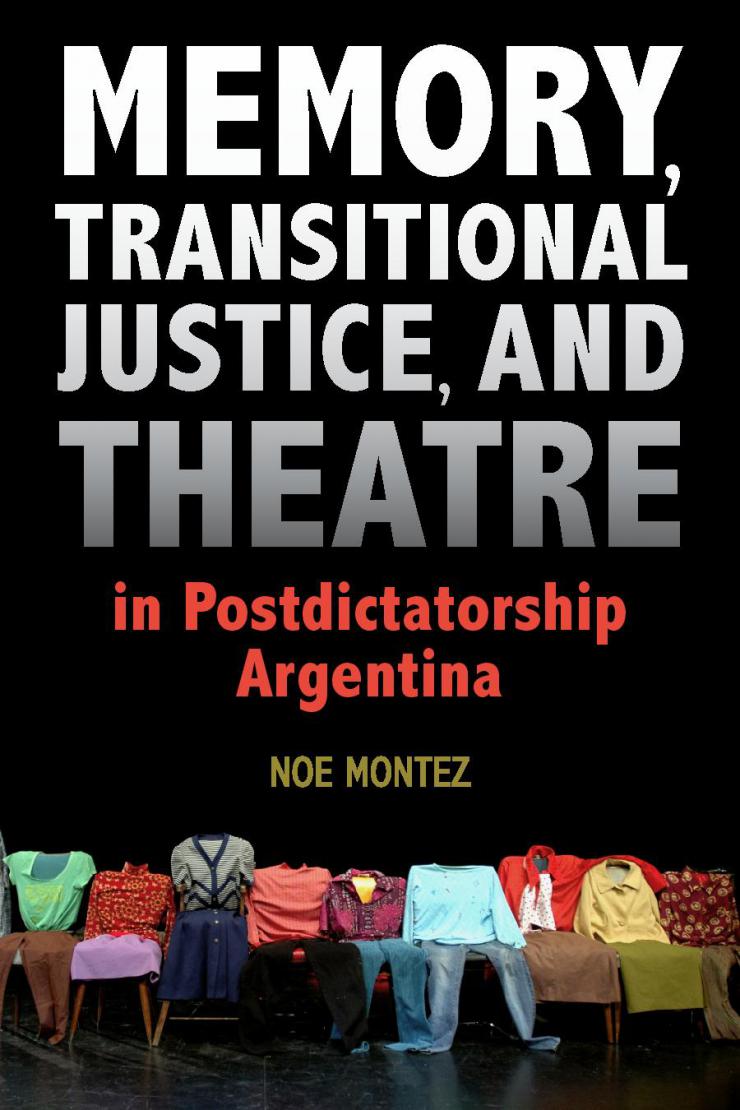

History can be a contentious subject, especially when it comes to determining how and what we remember. That’s especially true in Argentina, which is still trying to come to terms with the legacy of its period of military rule in the 1970s and 80s, which resulted in the deaths of tens of thousands of citizens. Theatre has been an especially important way for Argentinians to remember and reflect upon this dark era, a process which Dr. Noe Montez of Tufts University explores in his new book, Memory, Transitional Justice, and Theatre in Postdictatorship Argentina. Noe joins us to talk about his book, and about how Argentina’s theatres have served as an important part of the nation’s collective memory.

Links:

- Visit Noe’s author page at Southern Illinois University Press to learn more about the book.

- Watch footage from Lola Arias’s Mi vida despues on YouTube and learn more about it on her website.

- See footage from Federico Leòn’s Yo en el futuro.

- Watch a part of Mariano Pensotti’s El pasado es un animal grotesco.

- Learn more about the Theatre for Identity Festival at their official website.

Additional Reading:

- Exorcising History: Argentine Theater Under Dictatorship, by Jean Graham-Jones, explores theatre produced during the period of dictatorship in the 1970s and 80s.

- Theatre, Performance, and Memory Politics in Argentina, by Brenda Werth, examines how theatre and the politics of memory have intersected in post-dictatorships Argentina.

- Queering Acts of Mourning in the Aftermath of Argentina’s Dictatorship: The Performances of Blood, by Cecilia Sosa, looks at how violence in Argentina led to a new sense of togetherness.

- The script for Marcelo Bertuccio’s Señora, esposa, niña, y joven dese lejos is available online in Spanish.

Transcript:

Michael Lueger: The Theatre History Podcast is supported by HowlRound, a knowledge commons by and for the theatre community. It's available on iTunes and howlround.com.

Hi and welcome to the Theatre History Podcast. I'm Mike Lueger. How do we use theatre to remember the past? Can a performance make us rethink a historical event that we thought we understood? Those are two crucial questions that have marked theatre in Argentina over the past two decades. Today, we're joined by Dr. Noe Montez, whose new book, Memory, Transitional Justice, and Theatre in Postdictatorship Argentina, wrestles with these questions in the context of the country's recent history.

Noe is an associate professor in the Department of Drama and Dance at Tufts University where he's the Director of Theatre and Performance Studies PhD program. He's also currently serving as the co-editor of the journal, Theatre Topics. Noe, thank you so much for joining us.

Noe Montez: Thanks for having me today, Mike. I look forward to the conversation.

Michael: Tell us about the historical background to your book. What are some of the issues that Argentinian theatre has been wrestling with for the last few decades?

Noe: Sure. So, I'm going to take you back to the end of the nineteenth century and do a long way around to where I started. Theatre's always been one of the principle cultural ways of understanding what it means to be Argentine. Buenos Aires is a remarkably large theatre producing city. On any given weekend, you can see several hundred productions in bars, in theatres, other public and private spaces.

Dating back to the end of the nineteenth century, early twentieth century, as European immigrants were coming to Argentina in search of economic opportunities, the theatre has been a space that's tried to connect with and engage with working and middle class audiences to speak to issues concerning their own interests. From 1900 to 1923, for example, the number of theatre attendees quintupled from 1.5 million attendees to 7.3 million.

So, it's important to start by contextualizing Argentina in the twentieth century as a place that's deeply connected to its theatre. During the dictatorship, which was a period from 1976 to 1983, there were a number of political and cultural pressures placed in the Argentine theatre. In short, the number of plays produced by Argentine nationals in Buenos Aires' major theatres began to diminish. At some of the nation's largest schools and educational institutions, the coursework designed to promote contemporary Argentine plays started to fall away and more and more European touring companies began to come into the Argentine vernacular.

It was a time of theatrical crisis, and this coincided with a dictatorship that restricted what Argentines could publicly do or say. I think most people are familiar with this dictatorship under the auspices of the term "dirty war", which is a term that a lot of contemporary scholars contest the usage of. But during that time, over 30,000 Argentines were kidnapped and disappeared. In the aftermath of that dictatorship and in its waning years, several theatre artists began to think about how they could use their spaces to reengage with society in a number of issues.

But consistently in the now thirty-five years since the end of that dictatorship, theatre artists have thought about Argentina's transitional justice practices and memory practices in the years following that period and how they could engage with human rights organizations and other human rights efforts to advocate on behalf of policies in favor of commemorating and repairing the tensions that have existed in the nation.

Michael: Yeah. Can you tell us a little bit more about that concept of transitional justice and maybe in some ways, how it relates more closely to the theatre of Argentina?

Noe: So, transitional justice in sum is a multifaceted practice that combines legislative action, judicial measures, and for the sake of this project, cultural production as a response to political outrage and as a way to call for accountability after a period of authoritarian violence or other restraints on human rights.

There's not a series of clear policies as to what the best measure to produce transitional justice are. But Argentina has long been seen as a leader in post-dictatorship transitional justice throughout South America in comparison to spaces like Chile, like Uruguay, like Brazil. Following the dictatorship, there was a period in which there was a public memory commission convened to essentially get a sense of the full scope of the atrocities of the dictatorship. That convening had to close earlier than people would have liked and the justice process got stalled due to a number of political and military tensions that emerged shortly after those first years of the dictatorship.

For a good fifteen to twenty years, there were political efforts designed to promote a sense of forgetting or moving past the atrocities of the dictatorship, even though human rights organizations like the Mothers of the Plaza de la Mayo, who many of your listeners may be familiar with for the white handkerchiefs they wear over their heads, marching in the plazas of Mayo in Buenos Aires. There are a number of human rights groups like them who have been advocating on behalf of rights to ensure that people can gain full access to information about their biological heredity or information about what might have happened to people who were disappeared in this period.

As a strategy for helping the public to continue keeping these issues fresh in their mind, there were occasions when it served human rights organizations to collaborate with theatre makers as a way of ensuring that that discourse stayed in public circulation. Sometimes there were theatre artists who, even without the close connection to human rights organizations, felt as though they needed to create dramatic works that could engage with the post-dictatorship feelings at particular historical moments in Argentina's recent post-dictatorship period.

Michael: Speaking of important historical moments in Argentina's history, this dictatorship ultimately fell and, at least in part, it seems, because of its defeat by the United Kingdom in the war over Las Malvinas, which English speakers may know as the Falkland Islands. This seems like a very complicated and painful event. I'm wondering how theatre makers in Argentina have engaged with it.

Noe: So, Argentina has a deep connection to the Malvinas that dates back hundreds of years. Argentina claims that they have rights to the island and that the islands are a part of Argentina. So much so that it permeates every aspect of cultural life. Even though the islands are separated from mainly Argentina by several hundred miles, for instance, they still appear on national maps or their weather still gets covered by national weather people.

So, the dictatorship was already beginning to decline in its powers. As a last gasp to galvanize public support on their behalf, they decided to embark on a military endeavor against the United Kingdom to try to take the islands away. Now, at that same time, the UK was governed by Margaret Thatcher and she was looking to cement her own power throughout the United Kingdom. Thatcher used the full force of the British navy and British military to essentially make short work of the Argentine military during the course of this conflict.

That brought about a much hastier end to the dictatorship. But the Malvinas still play a significant role in Argentine cultural life and presidents since the end of the dictatorship have long felt as though they have attention of trying to remember the war efforts of the men who fought and died in conflict while trying to evade the fact that these men were working under military officers who were very much a part of the power structure that enforced the dictatorship.

So, what you see happening as one instance that I talk about in my book is on the 30th anniversary of the Malvinas War, and this is true at a number of major milestone anniversaries. There are a number of elements of cultural production that emerged. On that thirtieth anniversary, it just so happens that there were several plays grounded in thinking about the aftereffects of the Malvinas War and the Malvinas' legacy as a seminal moment in Argentine history. Some of these plays try to create a cultural overview, almost functioning as a sort of documentary theatre. Other plays try to tell specific stories about individual soldiers and their relationships with each other or their relationships with the family members that they left behind.

Even still, others try to engage with more quotidian aspects of the soldiers' everyday experiences. In doing so, these plays really get at the tensions that exist around how Argentines think about the Malvinas War. They want to remember the soldiers, the plays want to think about Argentina's history and its claim to possession of the islands, but they also want to escape having to think about the ways that the dictatorship pushed the nation into a war that it didn't need to venture into.

Michael: You say that a lot of Argentinian theatre has focused on debates about how the country's citizens remember its past. What kinds of historical narratives are these artists pushing back against and how do they go about doing that?

Noe: In the ’90s under the presidency of Carlos Menem. One of the major ideas that emerged from his presidency is the need to move beyond thinking about the atrocities of the dictatorship so that Argentina could focus on a number of things, predominately accumulating capital and ensuring that the nation's economy continued to develop in a strong and robust way.

Menem wasn't particularly successful at ensuring the longterm sustainability of the economy, but that's a little bit of a tangent away from the specific question. But basically, Argentine theatre artists began to use a number of aesthetic techniques ranging from multi-textual and multi-referential collages to allegories that draw on familiar stories in Argentine national history as well as other tales that Argentines might be familiar with to absurdist productions that think about the very nature of identity.

Not as a way of directly contesting Memem's words, but as a way of encouraging Argentine audiences to think about how the process of creating memory as complex and multifaceted, drawing from a number of experiences that a person lives and feels within their daily life as well as a number of cultural references and historical narratives that are imposed on a person through hegemonic forces like a government and counter-hegemonic forces that might emerge in culture in other ways. So, there were a number of plays that began to think about this idea of memory and the ways that it's contested and constructed in order to complicate the audience's understanding of what they heard from their government.

Michael: Yes. Who are some of these artists whose work engages with that legacy with dealing with the dictatorship and its aftereffects?

Noe: So, one of the groups that I think about throughout the book is El Periférico de Objectos. They're an object theatre group using mannequins, puppets, figurines ranging from six inches tall to six feet tall to think about memory. I write about a production of Hamletmachine, in which looking at the Hamlet narrative as mediated by Heiner Müller using bits and pieces of Shakespeare's text as well as a number of other sources to think about strategies for resisting authoritarian messaging or authoritarian bodies that might try to control a particular way of knowing or understanding a text.

So, in the same way that Heiner Müller draws from Shakespeare to create this fragmented and difficult to follow narrative sometimes, El Periférico de Objectos are using puppets and the fragmented storytelling of Müller's script to really think about how control is imposed upon bodies. Artistically, they are controlling and manipulating the puppets and mannequins and other figurines onstage to engage in remarkable acts of cruelty, cruelty that can sometimes be very difficult to watch for an audience member. But the audience is mindful that they are seeing objects that have no control over their own movement or agency, being manipulated by human forces and, in seeing that, make connections between ways that authoritarian governments manipulate the body public.

So, another production that I think is really compelling from the late ’90s is a production by a playwright named Marcelo Bertuccio. It's called Señora, Esposa, Niña y Joven desde Lejos. So, Mother, Wife, Daughter, and Young Man from Afar. The play takes place in virtual stillness. It just features three women largely sitting in chairs in a row staring directly at the audience. The three women are engaging with their memories of the titular young man who disappeared during the dictatorship in their own ways of knowing and remembering him.

But at critical moments in the play, the lights are drawn completely and all we hear is the disembodied voice of the young man trying to communicate his life experiences. Throughout the play, he develops this linguistic malfunction so that he's no longer able to articulate his memories. In fact, even the very word "memory" begins to escape his vernacular. His final monologue largely consists of a bunch of consonant sounds and guttural efforts to try to make a meaningful language emerge. But ultimately, nothing substantive is communicated.

Again, it's the sort of play where the audience is made to see how the process of memory becomes more slippery over time, not only for that young man trying to communicate experiences, but for a family who remembers different elements about their son, husband, or father and the ways that those memories conflict with or are in competition with one another.

Following this period in the ’90s, early 2000s, there's another generation of artists who emerge, begin thinking about the process of documenting the archive. One of the artists who I find most compelling is a woman named Lola Arias. The work that she's produced that has circulated most widely in the international theatre festival circuit is a play called Mi Vida Después, or my life after. For this production, she's found six children of people who were connected to Argentina's dictatorial past in some way, some as military officers, some as the disappeared.

She's worked with them to collaborate on a quasi-documentary piece that draws from the parents' personal artifacts or from their life experiences as a way to communicate the traces of memory or traces of historical knowledge that get left behind and passed down to generations who have to try to mediate it and make sense of it in some way.

Michael: I'm most curious about a festival known as the Theatre for Identity Festival. Can you tell us more about that?

Noe: So, the Mothers of the Plaza de la Mayo get a lot of attention within human rights discourse and popular engagement with the post-dictatorship in Argentina. But there's another human rights group known as the Grandmothers of the Plaza de la Mayo who are equally worthy of consideration and conversation. They've advocated for forensic technologies that enable children and now young adults to find out through DNA testing whether they are the descendants of the disappeared.

So, in the early 2000s, many of the children of the disappeared biologically would have reached the age when they were college students. They're moving into young adulthood. The grandmothers wanted to get public word out about their testing practices and about the process of knowing one's biological identity and why that was so important. So, they engaged in a number of festivals, some of which were music, sports, modern art, etc. to try to get the word out about the importance of knowing biological identity.

But one of their most successful adventures was a festival known as the Theatre for Identity festival. What began as one play turned into multiyear, multi-play festival that's still running in Argentina annually to this date. The idea is that a number of playwrights during the first festival, as it was a combination of some of the nation's most venerated playwrights as well as some younger playwrights who would later find themselves staged in the nation's largest theatres and achieve commercial success, but they were invited to self-produce short pieces, fifteen to twenty minutes sometimes, that spoke to issues of identity.

Some of them are very deeply connected to the grandmothers' cause and think about biological identity and connection to the dictatorship. Others think about identity in a more broadly conceived way. But this is one instance where a human rights organization has partnered with theatre artists to create a really meaningful intervention on behalf of their particular cause. Even today, just yesterday, the Grandmothers of the Plaza de Mayo announced that the 126th grandchild had, through DNA testing, found out that he was indeed the immediate descendant of parents who were disappeared during dictatorship.

Michael: Yes. It sounds like this is still very much an ongoing process. I know this is the Theatre History Podcast, but this is very much Argentina's present as well, isn't it?

Noe: That's absolutely right. Just in the last week, Thanksgiving week, since I don't know when this will be publicly posted, several Argentine military officers, nearly fifty, were convicted of dictatorship-related crimes and sentenced to terms that ranged from just shy of a decade to life sentences. There are still many more trials connected to dictatorship-related crimes that are still happening in Argentina to this very day and that will be happening for the foreseeable future.

Michael: What lessons does Argentina offer us when it comes to theatre's ability to remember the past and get us to reconsider what we think we know about our history?

Noe: So, I think where the Argentine theatre is particularly instructive is in challenging efforts to try to present official national historical narratives about past events. There's a tendency, particularly after moments of significant historical and cultural trauma, for a particular way of knowing what this event was like, to begin to circulate among the nation's citizens. That ranges from how these historical moments are taught in schools to how they are talked about or not talked about within particular public spheres.

The Argentine theatre has been willing to challenge narratives, particularly in instances when they work to undermine the human rights process or work to forget the very real human bodies that were disappeared during this dictatorial moment in Argentina's past.

Michael: We'll post links in our show notes that will let you learn more about Noe's book as well as the Argentinian artists and theatrical works that we've mentioned in this episode. Noe, thank you so much for a thought provoking conversation on history and theatre in Argentina.

Noe: Thanks so much for having me, Mike.

Michael: If you'd like to continue today's conversation, please visit howlround.com and follow HowlRound and @theatrehistory on Twitter and Facebook. You can also visit our website at theatrehistorypodcast.net where you can find links to all of our episodes. You can email your questions and comments about the show to [email protected]. A big thank you to the staff at HowlRound who make this show possible. Our theme music is The Black Crook Gallop, which comes to us courtesy of the New York Public Library Libretto project and Adam Roberts. Thanks as well to Tim Kress, who designed our logo. Finally, thank you for listening

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here