Twelve Hours of Epic Tragedy with The Hypocrites

All Our Tragic, adapted and directed by Sean Graney and produced by The Hypocrites at the Den Theatre in Chicago, features all thirty-two surviving Greek tragedies by Aeschylus, Sophocles, and Euripides compiled into a single twelve-hour epic. The result is rather like a contemporary version of a Dionysian festival.

All Our Tragic asks what it means to live in society—what it means to act in relation to one another.

The epic includes seven intermissions of varying lengths and a vegan feast of Mediterranean food is served throughout. As Graney puts it, “When people eat together, and share ideas over food, they are more willing to digest, pun intended, each other’s ideas.” The breaks offer audience members a chance to reflect on and process the extended drama in manageable chunks. Audience members gather through the extended intermissions in clumps, making connections between story elements with strangers in line for food, and interpreting moments of the drama together.

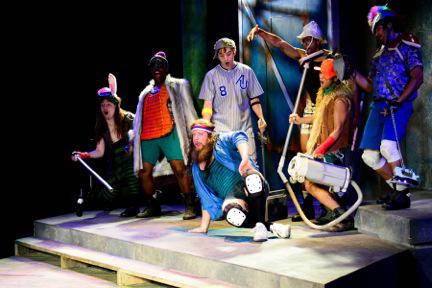

The piece dances between comedy and tragedy, intertwining moments of zany humor and irony with those of heightened language and serious themes. In sum total, All Our Tragic begins lighter and funnier and as the day progresses, grows darker and more serious. Graney remarks that in the extended process of workshopping and revising the show, he needed to walk a fine line to find the humor but keep the story progressing: “I think we need a laugh here, but I don’t want to sacrifice the story—so how can we get a laugh that helps tell the story?”

A map of how all thirty-two plays fit into the evening is drawn on one wall above the table of food. The audience sits alley style, in two sections of unequal size. On stage sits a large platform leading to an extended area of playing space. The upstage center edge of the platform features large sliding doors; at the opposite end stands a two-story structure with a balcony. The scenic design by Tom Burch creates a wealth of opportunity for dramatic entrances and exits. The scenery is painted weathered and old—as though it has survived the test of time.

All Our Tragic is structured in four parts, each engaging, in some way, the question: What does it mean for an individual to participate in a larger society?

Part I

Part I asks what it means to balance individual and collective needs— it looks at the consequences of actions, and this part includes the stories of Medea, called Médée (Dana Omar), and Phèdre (Christine Stulik). It is set in a mythic age of monsters and magic, and the central narrative is Herakles’ (Walter Briggs) journey to earn Prometheus’ (Geoff Button) approval as a hero worthy of freeing him. Herakles’ first heroic act is to save the Seven Sisters from forced marriage to a family of cannibal Cyclops. The Cyclops’ father, a spectacle-loving necromancer Eurystheus (Maximillian Lapine), vows his revenge on Herakles and curses the sisters to die in the order in which they were born.

Part II

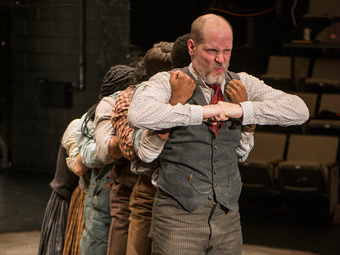

Part II examines the growing pains of a society that (in Part I), was comprised of loose tribes, but has now grown into large city-states requiring more formal governing structures. It focuses on Thebes, tracking the journey of Kreon (Ezekiel Sulkes)—an idealistic administrator with no ambition to rule—as his ideals come into conflict with problems far larger than he can control. He spends years attempting to write a constitution to codify justice in Thebes, but ultimately bends his own rules when he sentences his beloved niece Antigone to death. Through a narrative of interlocking stories (including The Bacchae, Oedipus, Seven Against Thebes, and Antigone), we watch Kreon become the kind of cruel ruler he never wanted to be.

Part III

Through the lens of the Trojan War, Part III asks how individuals define and treat “the other.” It begins with a group of soldiers fighting each other, restless and frighteningly aggressive after three years of waiting for a wind to carry them to war in Troy. Up until this moment, on stage combat has been comedic and cartoon-like; now the sequences grow scarier and more realistic. At the beginning of the war, enemies shake hands and treat each other with respect; by the end, they bash in the skulls of each others’ children.

The story of Achilles’ son, Neoptolemus (Ezekiel Sulkes) echoes the earlier transformation of Kreon (also played by Sulkes). Neoptolemus is a sweet, if slightly awkward, teenage boy who must learn to lie and kill to defend his father’s honor. In this warrior society, becoming a man also requires sacrificing the accepted moral code. Neoptolemus murders the Trojan princess Polyxena (Erin Barlow) in cold blood. Odyssa (Tien Dolman), a female variation on Odysseus, comments sagely at the fall of Troy that if the Trojan heroes Aeneas and Hector had marched a wooden lion through the gates of Athens, the story would be exactly the same (save the reversal of roles).

Rashaad Hall, Kevin Matthew Reyes and Danny Martinez.

Photo courtesy of Dani Snyder-Young.

Part IV

Part IV examines the role of free will in the cycle of revenge. It retells the fall of the house of Atreus, combining the homecoming of Menelaus (Ryan Bourque) and Helen (Emily Casey) with the more familiar story of Clytemnestra (Tien Dolman), Agamemnon (Walter Briggs), Elektra (Lindsay Gavel), and Orestes (Geoff Button). This bloody story plays out, but at the end, it begins to break down. Near the end of his journey, Orestes is exhausted, pursued by unseen furies. He begins to go mad as people he thought were dead are revealed alive.

Orestes tries to save Hermione (Erin Barlow) from an ill-fated marriage to Neoptolemus. When he arrives to intervene, Orestes finds Neoptolemus recreating the fall of Troy for “therapeutic purposes,” repeating the earlier scene, and the moment he decides to kill Polyxena. Everyone is confused—Erin Barlow plays both Polyxena and Hermione so Orestes (and the audience) doesn’t know which character she is. We are eleven hours in, the narrative is looping back on itself; the experience of disorientation reinforces the stage action. Finally Barlow removes her black Polyxena wig to reveal Hermione’s blond hair—Hermione has been playing Polyxena as a means of helping her new husband Neoptolemus heal. Hermione has taken control of her own narrative.

A chorus of three women who have been accompanying the evening with song enter to clean the stage and find Orestes alone. “You can leave at any time,” one of them points out, “The door is right there.” The full ensemble enters, wearing street clothes, and each is introduced by the names of their characters as they lay peacefully down onstage, either dead or asleep.

At the end of the bloody chronicle, Orestes is the only character left alive. He surveys the ensemble, wakes Tien Dorman, and has her put on Clytemnestra’s dress. The two re-play a variation on their final scene together in which Orestes does not kill her. He forgives himself, and in so doing, ends his flight from the invisible (perhaps non-existent) furies. The lighting shifts to reveal rusted out patches of orange covering the set. It’s as if the old world had caught a plague, now lifting.

In excising his furies (and free will), Orestes ends the cycle of violence.

All Our Tragic asks what it means to live in society—what it means to act in relation to one another.

After the curtain call, Graney asks:

After we’ve lived through this twelve-hour event with each other, what is our responsibility? Do we have a responsibility? If so, what is it? What questions should we ask ourselves? How should we look at the people we sat next to, and should we give strangers the benefit of the doubt?

Graney hopes audience members will find connections to each other through the experience of the event, and that the common bond felt by audience members is one we should, perhaps, share with all humans.

All Our Tragic is a marathon for the artists and the audience alike. The communal experience opens up opportunities for dialogue and critical reflection that can’t often occur at this depth without the commitment and physical exhaustion made manifest through this epic day of theater.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here