What IS a Feminist Play Anyway?

What Is vs. What Should Be

What does it mean to describe a play as feminist? What are you looking for when you put out a call for feminist scripts? This series is an exploration of possible answers from different angles by WITonline, a project of the League of Professional Theatre Women.

What is: too often, women are not assessed as fully human people. What should be: our humanity and personhood should be so obvious that this whole discussion would be considered absurd.

A playwright can depict the world as it is, the world as it could be, or worlds entirely fantastical. It is a fundamental artistic choice—the first choice a writer makes, perhaps. Where are we? What are the rules in the world of the play? Whether I’m writing a play, reading it, or sitting in the audience watching, that chosen world tells me everything. And I’m asking now: does the play’s world make a difference in how feminist (or not) the piece is, or can be?

Our reactions to women—as creators, as actors, as characters, to their presence and to their absence—are swift and strong. Getting under our assumptions is part of determining what is a feminist play.

We all have our subjective responses as we sit in the theatre. Are these characters familiar to us or are they different? Do we identify with the central premise of the play or does it baffle or offend us? We make these judgments so quickly and unconsciously sometimes that it can take some unpacking to recognize our own preferences and assumptions. Our reactions to women—as creators, as actors, as characters, to their presence and to their absence—are swift and strong. Getting under our assumptions is part of determining what is a feminist play.

Sandra A. Daley-Sharif is one of New York theatre’s Swiss Army knives. A playwright, actress, director, dramaturg, Co-Artistic Director of Liberation Theatre Company and OBIE winning producer for Harlem 9, she not only makes her own artistic choices but sees a huge range of work from affiliated writers. “The answer for me is in writing fully fleshed out, dimensional women. That in itself is a feminist play. Women as protagonists. Women as they truly are in all their forms. Even a stripper, a hooker, a drug-abusing mother can be the lead in a feminist play, as long as she is honored and depicted with the full complexity of her life. Why!? So they/we can be affirmed as real and as human.”

In Honour, a surprisingly fun play by Dipti Mehta, the daughter of a woman sold into the sex trade confronts the stark fact that her mother is in the process of auctioning off her virginity. The girl wants to be a doctor, wants to have a boyfriend, wants to live on her own terms—but that’s not what happens. She is indeed sold off, but her mother arranges for her to experience a much more lucrative, safe, and comfortable experience of prostitution than she herself did.

Why surprisingly fun? Because playwright Mehta, who also plays all the roles in this solo drama, has made her characters alive, fashion-conscious, intelligent, tough, musical, engaged, mercenary, shrewd, idealistic, and prone to impossible crushes: human. The world of the play is not feminist, but Mehta’s perspective clearly is.

Says Mehta, “I wanted to look for humanity in this world. In the play, I didn’t want anybody to be the Bad Guy. I think every character is human, they’re just trying to live.” It’s a full world, it’s a lively world, it’s about the very relatable ambition of a parent to provide a better life for her child. But despite the beautiful costumes and dancing and music, Honour also very real and ultimately rather depressing. Mehta’s theatrical choices allow us to look at a reality we may want to turn away from, to see and hear these women (and men) as full people.

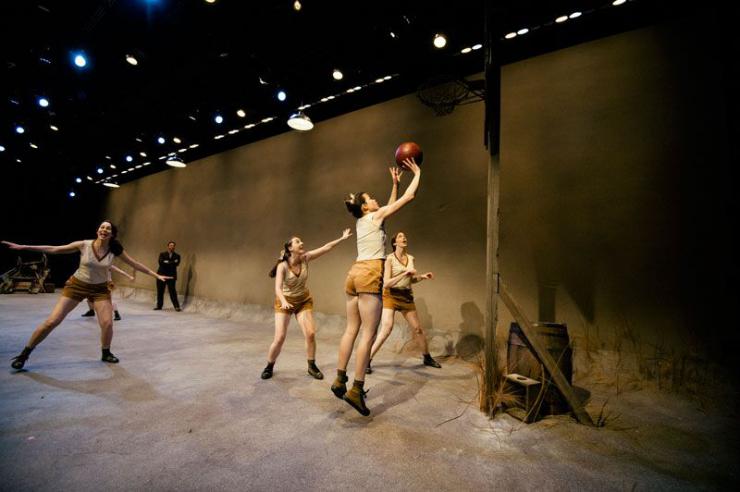

Plays written in the past—what gets referred to as “the canon”—all too often have few roles for women, and those roles can rarely be described as feminist. Meg Miroshnik is one playwright who is mining the narrow roles of women in society for theatrical punch that illuminates the present. “The past is about the present for me. In the period pieces, the constrictions are explicit and legislated; in the present, they're subconscious and socialized. The period setting throws the problem into relief and makes it more visible in the present, I think. For instance, in thinking about Lady Tattoo, I was inspired by an anecdote about Winston Churchill's mother, Jenny, sporting a snake tattoo around her wrist. That felt so shockingly contemporary. Similarly, I started writing The Tall Girls after reading about how incredibly popular girls' and women's basketball was from the time the game was invented in 1891 until it was all but stamped out in the 1930s.”

So wherever or whenever a play is set, whatever kind of people inhabit this world, there is room for a feminist perspective, as unconventional or doctrinaire as a playwright chooses. Whatever a feminist play is, it’s not about shutting doors and declaring “you can’t talk about that.” Historical play, science fiction, any class, any race, experimental or straight-forward, there is no formula for a feminist play because there is no formula for how to be human.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here