An Interview with Morgen Stevens-Garmon, Theatre Archivist at the Museum of the City of New York

How did theatre become the way it is today? This blog series will look at aspects of our present-day theatre that we take for granted and explore where they came from. It will also feature interviews with theatre archivists about their work and how it relates to new theatrical productions.

Michael Lueger: How did you get your current job?

Morgen Stevens-Garmon: I’ve always been interested in theatre. I’ve always wanted to be a participant in some way. I took a few years off after graduating college—I went to the University of Arizona in Tucson. I knew that I liked thinking about theatre and I liked talking about theatre. So I went back to school and got a Master’s in Theatre History from CUNY Hunter College. And while I was there, my thesis turned out to be about this play called Peculiar Sam, or the Underground Railroad by Pauline Elizabeth Hopkins. She was an African-American woman, who later in life wrote novels and wrote for magazines. When she was in her early 20s, she wrote this play that was performed in Boston during the 1870s. I looked into this play and realized that after its first big publishing, no one knew this play existed, or that she wrote it. There were extent copies kept by a librarian at Fisk University. When I went to high school, I happened to live across the street from Fisk University. So, I went back to Nashville and looked at Pauline Elizabeth Hopkins’ papers.

I looked at her handwritten draft of the script, and that really inspired me to look at archives as a possible profession. I wasn’t super keen on the idea of getting a PhD because I wasn’t sure that I wanted to be a professor. But I did like the idea of helping scholars in some way; I really liked the idea of pointing them to various resources and saying, “Look! This is here. If you want to talk about it, or if you want to think about it or if you want to use it, please do.”

I went to Pratt Institute in New York; part of the reason why I picked Pratt was that they offered a class called “Performing Arts Librarianship.” Coming out of school in 2009, it was really hard to think about getting any kind of job anywhere. So, I did what a lot of archivists have to do, which is taking a lot of short-term, grant-funded jobs. And then I got a job at the Museum of the City of New York, on their digital project. I was looking for a more permanent, more stable job and the theatre curator at the museum was retiring. So I put my name down to be his replacement. I interviewed for the job, and got offered the job, and took over the job in July of 2010.

Michael: How does working in a museum differ from working in libraries?

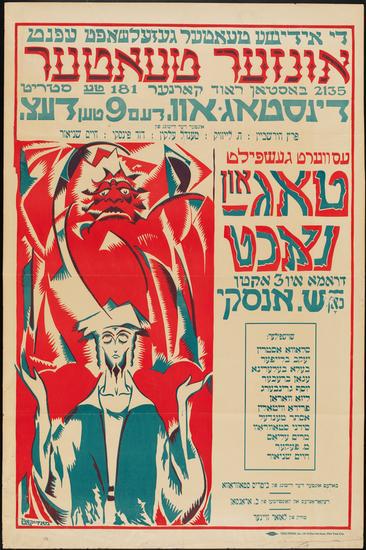

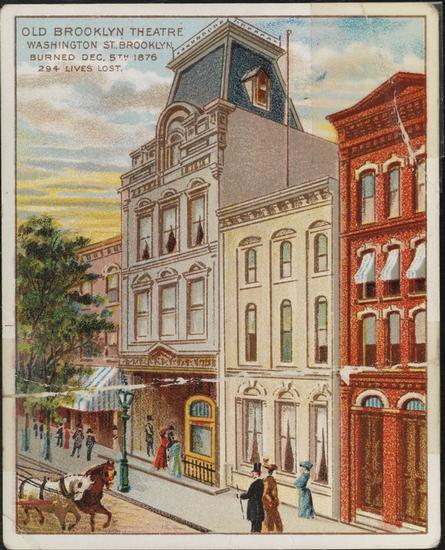

Morgen: You know we’re a little bit unique in America as far as a theatre collection existing in a museum context. There are only a couple of other places in the country where they have that. Our primary users are the staff and curators associated with the museum. The goal, or the mission of the collection is to support the activities of the museum, which includes exhibitions, public programs, family programs, and things of that nature. We open the museum up to outside researchers; and scholars are certainly welcome to come and access the collection. We’ve also created the digital portal so that people can access this information from the comfort of their own home. For a long time, the Theatre Collection wasn’t necessarily described, or known in many circles. One of my major challenges has been to get the word out about the fact that the Theatre Collection exists.

Personally, I’m really interested in plays that were very popular fifty, seventy-five, and 100 years ago, but are never done now. I like looking at why that’s the case and finding ways to connect today’s museum audience with the audiences that enjoyed those productions in the early twentieth-century.

Michael: How does the Theatre Collection relate to what’s happening in contemporary NYC theatre?

Morgen: It’s something that we talk about here. I have conversations with my supervisor, and my colleagues about it because we haven’t been collecting since I’ve been here. And part of the reason that we haven’t been collecting is that we’ve been under a collecting moratorium for the entire museum. The Museum has been under full-scale renovation, which gives us the opportunity to do assessments of the collection and take a really good look at what’s in the collection, which hasn’t necessarily been done.

The first curator, May Davenport Seymour, was here for over thirty years. She came from an acting family and she was hugely connected to the theatre world. She took a lot of material, pretty much indiscriminately, from my perspective. If she had criteria that were more discerning, I don’t know it. It was also the same time that theatre was recognized as something that could be collected and accessed by scholars. So, there was a lot of crossover between collections, but there wasn’t necessarily a “You take this, I’ll take this” sort of conversation.

I have to fix that and I have to think about what is reasonable for the Museum to take stewardship of when we have limited space and resources? There are already institutions like the Performing Arts Library that are more set up for scholars.

Michael: What collections do you want people to know about?

Morgen: The collection itself is primarily focused on Broadway theatre, and I think we’ve excellently traced musical theatre. We have a large collection from Harry Bache Smith of musicals from the 1890s well into the 1900s. We also have the papers of George M. Cohan, who produced early twentieth-century musicals. Then, we have papers from Betty Comden and Adolph Green, Howard Dietz, and Mary Martin. There are many different ways in which you could trace the evolution of musical theatre—a very American, made in New York art form. So, I think that’s a real strength for this collection.

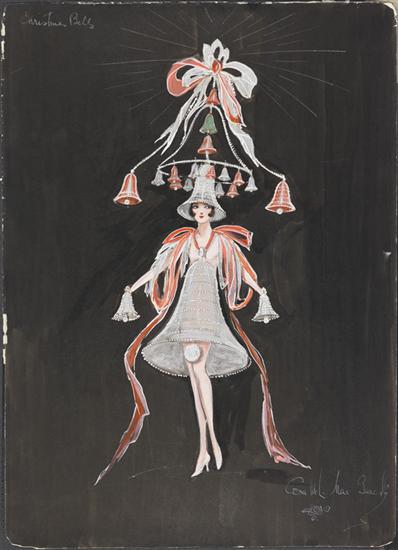

I also think that our design renderings are a real strength as well. We have large collections by costume designers Alvin Colt and Miles White. These are unique designs that are colorful and include swatches. We have renderings from a lot of designers from the 1920s, who created pretty outrageous and fun Follies costumes.

Michael: What would you like to see in terms of artistic collaboration using Museum materials?

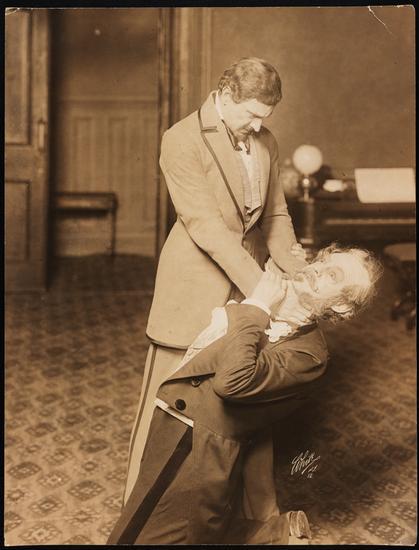

Morgen: Personally, I’m really interested in plays that were very popular fifty, seventy-five, and 100 years ago, but are never done now. I like looking at why that’s the case and finding ways to connect today’s museum audience with the audiences that enjoyed those productions in the early twentieth-century. Off the top of my head, the plays of Clyde Fitch come to mind because they were immensely popular back then and are now never done. I’m interested in looking at that and how we’ve changed. What has changed in why things are popular? What hasn’t changed in how we consider good theatre?

To see more of the Museum of the City of New York’s theatre-related treasures, check out their online Collections Portal here.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here