Cartography of Flood Plains

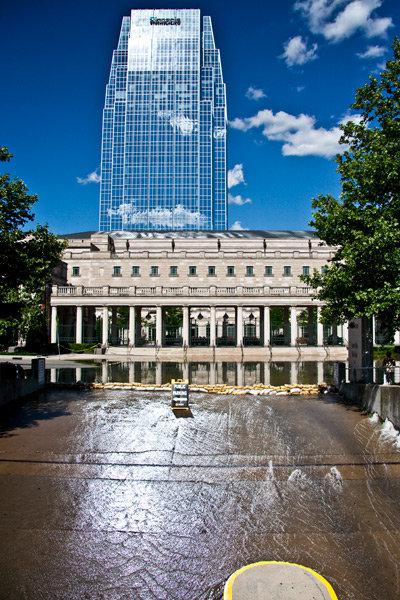

Nashville, Tennessee is well known as the Music City, but the rest of the performing arts scene doesn't get much attention. This series highlights Nashville’s lively artistic community, built on a foundation of interdisciplinary collaboration. In this “It City,” artists are paving a way forward for live performance while wrestling with an economic boom and rapidly changing needs for representation on our stages. In 2010, Nashville experienced a severe flood that took twenty-six lives regionally and caused billions of dollars in property damage. Like an unwanted baptism, this flood also marked the beginning of the city's incredible growth. Audra Almond-Harvey, a respected poet, performer, and administrator, reflects on this flood as a personal turning point and encourages us to consider what repairs we still need to make for our community.—Daniel Jones, series curator

The rains fall heavily in Nashville, when they do. No one carries umbrellas, really, we just rush through puddles pooling in parking lots on the way to the car and then show up a bit clammy to our next meeting. We chat briefly about how the 440 loop is impossible all the time but more so during a storm, and then we move on to business.

It’s easy for some to forget the rising waters.

One night in 2010, I sat with my small child and my dog, in my house in Nashville’s urban core, as the rains just kept coming. The dams almost didn’t hold, and the waters slowly rose to swell past the banks of the rivers and streams, flooding the streets over a matter of days, almost swallowing us. I saved water in my tub just in case and found all of our flashlights and batteries for when the power went out. My neighbors knocked on the door, making sure we had water to drink—you wouldn’t think you would have to worry about dehydration in a flood—and let me know that they were sandbagging up near the water treatment plant but that I should stay put so that my child and I were safe. “We’ll make sure you know if you need to evacuate.”

Eventually the waters receded, and it was time to restore. We topped up on our tetanus shots and then joined in the efforts to muck out our neighbors’ houses. One day, as I sorted through soggy photographs drawn from a moldy box in a stranger’s basement for the pictures that survived, I remember thinking to myself, All this was here all along, all the things we thought we couldn’t part with. It was here before the waters rose.

Immediately after the 2010 flood, less than a mile from where the waters crested, you could find people watering their lawns while the rest of us endured water shortages. And even though we all knew better, as we began our cleanup efforts, getting rid of scores of old things, we still largely ignored the impact that our vast and sweeping renovations would have on the most under-invested of our people.

Waters of a different sort have been slowly rising in this town for years. I mean, hundreds of years. I mean, if you don’t regularly have to reroute down backroads to avoid these floodwaters spilling out high enough to reach the undercarriage of your car, then I know from what parts of town you likely hail. The most recent descriptor for this seeping flow is gentrification. We’ve called it by many names in the past. Separate but equal, for one. Some of us are able to go about our days without a hint of damp. Others might need waders just to get to the grocery store.

To some people—like those who favored their own cleanliness over their neighbors’ need of water to drink, and those who tore down the old to make room for the new, seemingly with little thought—the rising torrents of discrimination and segregation that still roll through our hills are only slowly encroaching, rarely causing even a small delay. I believe what colors this view is a lack of proximity to the individuals in our city who are most affected. Many have already left us for elsewhere, escaping to avoid being taken under, and we have most likely already forgotten the stories they told.

What is a city without its creators? Those cranes dotting the skyline can’t build or repair a culture.

And we move on, without regularly taking stock of the changes that have been wrought as we shift around to make room for new players and stop talking about those who left us behind.

Overall, the resource pool for artists has certainly increased since the flood. But the talent drains we suffer and the rapid shifting of our city’s landscape transforms our collective identity so rapidly that by the time a movement or moment is identified we’ve forgotten how it began. Sometimes we still have to do our best to make a lot with only a little. Considering these challenges, it is certainly understandable that we regularly face the temptation to become insular in both our focus and our programming. But to make real and necessary change, we must be aware of our strengths, despite our continued lack. We must take stock of our influence, of all the creative power we own that cannot be truly represented in dollar signs alone. Of what we can accomplish together.

What is a city without its creators? Those cranes dotting the skyline can’t build or repair a culture.

All we were asking ourselves ten years ago, even five years ago was, “Will anyone show up?” But now we have audiences. The most obscure performances are presented at venues around town to standing-room-only crowds. People press in towards the stage, they ask questions after the performance, they throw themselves into the improvisational and immersive programming we thought we’d have to drag them through. They want to learn more about our sources of inspiration, they catch the subtle undercurrents that we used to have to spell out in our press releases and programs and then reference again in the poster just to be sure.

Working artists in Nashville are as often found discussing infrastructure, affordable housing, transit, food deserts, cultural erosion, and systemic disparities just as we are found exploring our characters’ backstories or the metaphors we’re playing with in our choreography. A great bit of the work examining these issues and their many layers is happening in contemporary art spaces. Artists like Joe Love, Thaxton Waters (I wish attendance at his Art History Class and Lifestyle Lounge could be required for all artists moving to Nashville), and Kristen Chapman Gibbons have been working for years to build connections between genres and to offer opportunities for artists of all kinds in Nashville, and post-flood, have contributed to the organizing and educating of our arts communities. While no longer extant, the People’s Branch Theatre regularly produced confrontational work in their ten-year run, and many of their former artists are now leading efforts to improve our scene today in a variety of venues. Local director Jon Royal has been active in Nashville for twelve years and has advocated for more opportunities for performers of color throughout his career. Leaders like Vali Forrister, Cathy Street, and Jessika Malone have been holding space for thought-provoking and new interpretations of classic works, works written by new playwrights, and immersive and non-traditional performances, all of which previously struggled to find a home in Nashville.

Connections across genres are proving invaluable to us all. One example is in the dance community, which has grown so vibrantly that they craft well-choreographed engagements with multiple genres, including theatre. I work in an interdisciplinary arts space, helping artists from the dance and theatre community join with visual, literary, and musical artists, and we were only able to get our plans off the ground because of the support of visual artists like Lain York. I sat down with Lain in 2011 at the (recently-closed) Provence in Hillsboro Village and took copious notes while he generously gave me the beginnings of a roadmap for how to make a home for artists in this city; he and his co-conspirators have been working to provide strategy for sustaining and supporting the arts since the days of the Fugitive Art Center, back in the early 2000s. And I can’t imagine what our arts community would even look like without tireless literary arts champions like Stephanie Pruitt, who has worked for years to ensure that artists know their own stories and tell them frankly and justly.

But we are nowhere near done with examining the important questions affecting contemporary artists in Nashville of all genres. Our next great undertaking will be exploring how we might continue to forge paths for the experimental and exploratory work we have yet to even consider, whilst building connections with the people in our city who might find that they would love to be patrons—if they only knew why. But if we continue forward without comprehensively dismantling the inequalities that still plague us—racial and gender disparities, lack of access to a living wage, oppression against all minorities—what will any of our artistic work even mean?

I was one of the newcomers once, one of those folks who carried my Southern identity in a shaky grip. I said I wasn’t one of those people from the South; I hid behind my continental accent and metropolitan fashion. A white-passing person of color struggling to keep all my facades together while also trying to craft work that was meaningful. Though I do believe I have contributed to the progress we have made, it is also true that until I comprehended how many artists had gone before me, mapped the grounds they had gained and lost, and took ownership of my own issues with identity, I could only hope to bring change.

If we continue forward without comprehensively dismantling the inequalities that still plague us—racial and gender disparities, lack of access to a living wage, oppression against all minorities—what will any of our artistic work even mean?

My love for this city is not blind. It is characterized by open-eyed awareness: there is much work left to be done to address our shaky infrastructure, both literally (I’m not even going to start on the current transit debate) and figuratively.

If the only query we still have is “Will they show up,” we may as well quit now. That has been solved. We can retire and spend our time sipping cocktails on 12 South, telling our anecdotes about how it was, enjoying the light warming our faces on sunny days.

The questions must go deeper. We need to be far more precise. Perhaps we could begin with “How will we remain here” and “How will we sustain here.” Or, “Who and what have we forgotten” and “Whom have we spoken over” and even “What stories did we give up telling because we could not forecast the tickets sales for them.” These questions are imperative not only here in Nashville, but in all places in which the creative class is poised to direct the future growth of their cities and towns.

The waters are still rising. Relics from the conflicts and traumas we have stored in dark closets and basements—because they were too messy to deal with before—will only be more wearisome to face later if we continue to leave our histories to decay. After the waters receded in Nashville in 2010, the tribulations were not over. No one tells you how hard it is to clean up and rebuild after; flood waters don’t just make everything wet. Strewn debris, fallen trees, broken buildings, sewage waste in the streets—the restoration went on for a long, long time. And yet, right now in Nashville, we are building new residential and commercial developments on flood plains. How quickly we forgot how high the water rose.

We must be aware of the marks we are leaving. If we remain ignorant of our impact, we will only create things, possibly beautiful things, but they will live for only a moment and then disappear into the collections of stuff we do not really need but would hate to give away. Perhaps they will surface again, the next time it floods.

Wherever you create, learn from our history. The cleanup and restoration that must follow many years of racial and gender inequality and oppression will be extensive. It will last long after your passion for change gives you grace for daily aggravations. None of us can complete this work on our own. But should artists join with those who have gone before us—the makers, thinkers, and creators who have kept our stories, survived these traumas, and learned how to rebuild—we will be able to speak louder and with more vigor than the voices who would prefer to whitewash our history and disregard the lessons learned. Perhaps we can rebuild and restore our culture from within.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here