Creating Diversity in Oklahoma’s Performing Arts

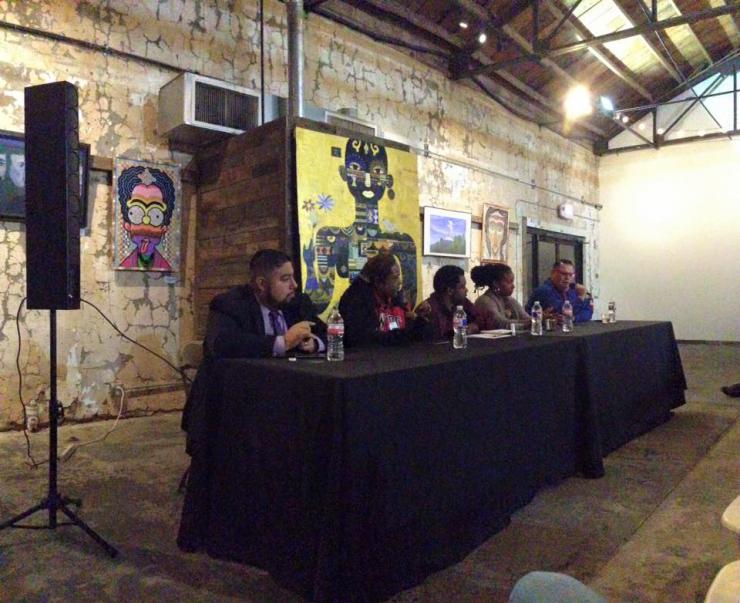

It is a beautiful time to be an artist of color when even in Central Oklahoma—the nation’s heartland and, Norman specifically, an unexpected cultural destination—there are sincere conversations transpiring over how to expand diversity in a seemingly white, homogeneous community. On November 12, I attended the inaugural “Diversity in the Arts” forum that, though particularly concentrated on the blossoming Visual Arts community, included actors, musicians, arts educators, and leaders speaking for their own niches. Having become accustomed to being one of few shades of brown present at any gathering in these parts, I was initially struck by cultural variety in attendance. This was not only reflected in the audience, but also in their formal panel, which included a Latino musician, an African American painter, an African American art professor, and a Native American artist/curator.

The evening began as a moderated panel discussion, but quickly evolved into a room-wide discussion with the more than one hundred attendees jumping in, asking questions, and offering implementable suggestions in the pursuit of a more diverse landscape for their community. It was beautiful.

The focus of this discourse centered on expanding the programming offered by the local arts council and the work displayed in their showcases. Many ideas were raised about presenting work from artists of unrepresented ethnic/cultural groups and even building a calendar that would ensure diverse representation. The puzzle this presented was, of course, identifying who these artists were before any discussion of hanging their art could begin. Though highlighting these unidentified artists is certainly the desired outcome, I feel that the approach as a whole is a bit misguided. The emphasis on the diversity of the “art on the walls” is imperative, but I maintain that the only way to achieve true parity, without “color quotas” or “ethnic slots,” is to shift that focus to developing a diverse group of people deciding what art should be on said wall. This holds true for the way we should program theatrical seasons.

Some of my first experiences producing theatre professionally were with a small company in Houston, TX—arguably one of the most multicultural cities in the United States. That artistic landscape includes a diverse range of theatres: from the historic Ensemble Theatre (highlighting the African American experience), Talento Bilingüe de Houston (focused on the Latino Arts experience), and the Shunya Theatre (providing a voice for the South Asian American experience), to the sundry seasons offered at the other seventy-five theatres in the metropolis.

The company I worked with was spearheaded by an African American Artistic Director and a diverse staff. The inherent outcome of these variegated voices contributing to every conversation, particularly on programming, was a diverse mix of ideas and plays brought to the table. This was not strategically organized or an intended goal, but the result of our varying ethnic and theatrical backgrounds. The purview of material in our individual libraries/mental catalogs drastically expanded the scope of reference for the company as a whole, making our creative pool that much more culturally multifarious.

Comparatively, in my time producing in Oklahoma and Southeastern Minnesota, I am usually one of the few faces of color “behind the table.” The work that I have made and seen seems to be almost ubiquitously by, with, and for white artists and audiences. These two observations cannot be unrelated.

Examining the demographic of these regions, I do find this to be understandable. But does understandable imply justifiable? Non-profit theatres walk a fine line in creating art that is representative of their audiences/community while remaining true to their legal status as educational entities, which—I purport—includes a responsibility to educate their audience with something new and, dare I say, different.

It would be unfair not to mention the many examples of “color-blind casting” I have seen; this is a good sign of progress. But how long can theatres sustain a reputation of inclusion by only including those who are different on the stage, rather than exploring new stories by the many creeds and colors that are emerging in this art form?

How long can theatres sustain a reputation of inclusion by only including those who are different on the stage, rather than exploring new stories by the many creeds and colors that are emerging in this art form?

In my eager optimism, I do not believe that a lack of inclusion implies decided exclusion. I do not believe that diverse programming doesn’t exist because our voices aren’t important to these theatres or even that they have a staunch desire to produce sameness. It must be, then, the product of a narrow scope of theatrical exposure, consistent among immutable artistic and executive staffs. When brainstorming new programs and analyzing suggestions for season consideration, the same types of plays and playwrights are brought to the table. So, the result is understandably restricted. Again though, does understandable imply justifiable?

How, then, do we expand the voices that join this producing conversation? In a recent tête-à-tête with an Oklahoma Arts leader, it was insisted that as long the middle-aged anglo demographic remains at the helm, it is our responsibility (the many “other” voices) to submit work from our cultural pockets to them: that they can, then, consider for production. The onus, she implied, is on us if we want to be produced. With respect to her and her genuine desire for the theatrical landscape to broaden, I cannot accept this approach as sufficient. Further, I detest the idea of “us” versus “them.” I prefer to think of all artists as a greater “we” and that, when we are collaborating with people from as many walks of life as can fit in the room, the greater “we” becomes much stronger. Romantic, I know. It is not my belief that in our personal lives or social settings we must have a diverse demographic of associates, but professionally, if we want our work to be at its strongest and most inclusive, we must! This must be our priority.

Without diverse artistic leaders and advisors, any theatre’s pursuit of diverse programming will become wracked with color quotas and host only a narrow pool of overly-produced writers of color, and the market, as a whole, will follow suit and suffer. Diversity cannot exist only in the product; it must be an integral part of the process. Initiatives should be made, not just to program “exotic” work, but to foster the multicultural leadership necessary to create ample representation and inclusion. The tenure for our understanding and blind acceptance has expired. The recognition of this need has been announced and widely agreed upon, thus the current status quo can no longer be justified. Only with artistic leaders and contributors of color will theatres and other producing arts organizations achieve the goal for which many claim to be striving.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here