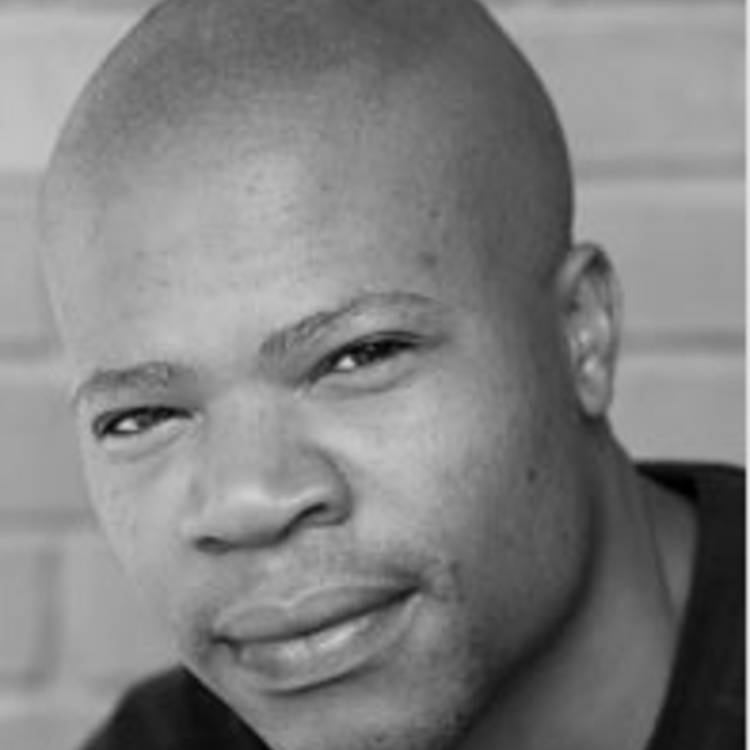

Interview with Thando Doni

This is the final interview in a series profiling Cape Town-based theatre artists and companies who presented work at the 42nd Annual National Arts Festival (NAF), held from 30 June through 10 July 2016 in Grahamstown, South Africa.

An eleven-day extravaganza of theatre, dance, music, fine art, and more, the NAF is the largest arts festival of its kind in the Southern Hemisphere and serves as a dynamic platform for both new and established artists from South Africa and around the world. It's my hope that these profiles will provide a tiny glimpse into the flourishing theatre ecology of South Africa and to the questions artists in the country are posing through their work.

To read the other interviews in this series, click here. And to read my review of the 2016 NAF, click here.

In his plays, theatremaker Thando Doni explores contemporary issues—both grand and intimate—through a stirring and potent physicality. Honed during his training at Cape Town’s internationally-acclaimed Magnet Theatre, Thando's blend of captivating physical storytelling and confident, sensitive direction has made him one of South Africa's most exciting directors. Working within the workshop (or “devising”) tradition that produced some of South Africa's rich theatre of resistance, Thando collaborates with performers to pose urgent questions about history, identity, language, and love. In his most recent play, Ubuze Bam, he worked with three ex-inmates to explore both the hope and despair inherent in their narratives of incarceration. And in his play Passages, Thando collaborated with a group of South African men to create a searching piece about rites of passage and masculinity. Thando often works in isiXhosa, and his plays explore the complexity of language, both spoken and embodied. His epic production, Ityala Lamawele (co-directed with Artscape Theatre Centre's Mandla Mbothwe), garnered a Silver Standard Bank Ovation Award after sold-out performances at this year's National Arts Festival. An adaptation of an isiXhosa novel by Samuel Edward Krune Mqhayi, the play tells the story of a dispute between two twins over their inheritance. Thando sees Ityala Lamawele as a “history lesson” that offers a way to celebrate and reclaim Xhosa traditions and legacies.

I sat down with Thando to hear more about Ityala Lamawele and to get a sense of his journey up to this point.

There's a saying: ‘Art chooses you, you don't choose art.’ I'm a firm believer in that. It chose me.

Paul Adolphsen: What is your earliest memory of theatre or performance?

Thando Doni: [In high school] we did this play and I had a lovely role, which I wasn't doing so well. So, the day before the performance, my director came to me and said: “Dude, you are not pulling it, so we have to give the role to someone else.” And they did. I had already invited my parents and friends to come and watch me do theatre. [My new role] was [as] an extra; I was just passing by. After that I said, “This will never happen to me again. It just won't.” And it hasn't! Which is lovely.

Paul: What made you want to pursue theatre as a career?

Thando: There's a saying: “Art chooses you, you don't choose art.” I'm a firm believer in that. It chose me. There has been a series of events leading up to where I am right now, and if I was someone else, I would have quit a long time ago. I had to go through auditions and people saying “no.” It wasn't easy or nice. So [theatre] chose me in the sense that it made me stay. By making me stay, [theatre] made me fall in love with it. Up until now there's nothing that makes me happier. It pisses me off when you do things [in rehearsal] and they don't come together. But at the end of the day, that moment when the curtains go up and the lights go down, that's the thing that keeps me going. Also, just stories, man. Just telling stories and hearing stories, and being present. That's the thing that keeps me going.

Paul: What was the first thing you did after school?

Thando: I did some small shows, some industrial theatre gigs. I only started directing later. The first piece I made after I finished at Magnet [Theatre’s training program] was about a young man wanting to become a man. Growing up, there comes a transition period where you become a man. If that transition period has come for you and people still perceive you as a boy, then it becomes a problem. This character had that problem. In the play he wants to prove to his family and to his community that he is a man. But he goes about it the wrong way: he starts committing crimes to put money on the table. The play asked: “Which crimes are accepted, and which crimes are not?” It depends on the cause. That was the piece for me. When do we see things as they are and what causes us to shift and be on the side of the perpetrator? That's the thing about theatre: it's about creating a platform where we can all speak about things and debate them. Not because we have answers. As long as we find a platform where we can speak about things, that's enough.

How do we make sure that people become part of this world on stage and understand what we are speaking about by listening with their eyes? How do we make sure that the senses are a language in themselves?

Paul: All your plays that I’ve seen have been in isiXhosa. Why have you decided to work mainly in that language?

Thando: [My use of language] is a very personal thing. We grew up feeling that our language [isiXhosa] is not as good as English. Our parents sent us to school to learn how to speak “proper” English. The moment that people start realizing that their mother tongue is as important as every other language, we can start moving forward. We have been robbed of that pride, of saying that we can stand here and do work in our own language. A lot of the theatre being done here is in English. As a performer or a director, you have to understand English in order to get employment. But we live in a country that speaks eleven languages. It’s weird for me to live in such a country and see that the work we do is only English. It doesn't make sense. But I don't want, by speaking our own language [i.e. isiXhosa], to exclude others that don't speak the language. And so, in most of my work, the language is not only spoken but the language is also in the body. I'm physically trained so I believe a lot in body language, and how the body speaks—that is universal. How do we make sure that people become part of this world [on stage] and understand what we are speaking about by listening with their eyes? How do we make sure that the senses are a language in themselves? I like for a certain image or certain word to mean many different things, so that you can relate to it in your own way and I can relate to it in mine. I want to create a space that allows for that. And once you've done that, it just becomes too beautiful, man.

Paul: Let's transition to talking about the shows you're bringing to Grahamstown. What made you want to adapt Ityala Lamawele?

Thando: It's a classic. It's one of those stories we grew up with. It's one of those stories that we claim. It brings certain memories which sit in a place that is quite delicate and sensitive. It's a Xhosa story about our customs, our history, and our kings. It's also a history lesson for me. There is so much Western influence in what we do and what we see. How do we remind ourselves of where we've been, where we come from, and where we want to go? You go back to the basics, the roots. [Ityala Lamawele] speaks of our kings, our customs, our clans; [through that] we can begin to understand the people who lived before us and how they have influenced us now. If I had to adapt anything, it had to be [Ityala Lamawele]. Luckily I have a chance now [with the play] to go back and find pride in our history. Whenever we remember our history, we think about apartheid. But for most of our history, we had beautiful things and memories; we had beautiful people to celebrate, like kings and queens, elders, and witch doctors. We are forgetting these people who made marks in our lives. The only things we can think about are the bad things that happened in history. I'm not saying it's time to move on. It's not time to move on. But it's time to put in other memories as well. So we can balance things.

Paul: Could you briefly tell me what the story is about?

Thando: The show is about two twins. They are born on the same day. In the Xhosa culture the first-born becomes the heir to his father's wealth. [In Ityala Lamawele] the first twin [puts] his hand [outside his mother's womb]. To show that he is older, the family cuts off a finger. But then the hand goes back [into the womb] and the other twin is born. This twin does not have a cut hand. Then the other [twin] with the cut hand is born. So the question is: who's the eldest? [The play follows] the dispute [over this question]. The Xhosa elders get called to come and solve the issue since the people of the village don't know who the eldest twin is. They finally find an elder to come and solve the dispute. He [provides] the solution right at the end: you are old because of how you behave, not because of when you are born. He says that behavior tells us who we are.

Paul: How did you and co-director Mandla Mbothwe approach adapting this story?

Thando: I wrote the script. But you can only go so far with a script. The next thing was just to put it on the floor. Mandla and I devise things. Even if we have a script, we'll still devise the story with the actors so that we can get different perspectives. What came out [of the devising process] was beautiful. We started playing with songs, playing with movements, monologues, gestures, and idioms. We took things from old Xhosa rituals to see how they fit into the story. It was quite a fun process.

Paul: Let's talk about Ubuze Bam, the piece you made with ex-inmates. How did that project come about?

Thando: Young in Prison [YIP] and Theatre Arts Admin Collective [in Cape Town] called me in to work on a new project. YIP is an organization that works with ex-offenders. They wanted to create a play as part of the workshops and programs they offer. It was quite a tough process.

Paul: You were working with men who have never performed before, right?

Thando: All of them had never seen a play before, let alone performed. So here I am saying, on the first day of rehearsals, “Gents, we're going to do a play.” And then I needed to explain what a “play” is.

Paul: How did you work with that challenge?

Thando: There's one thing I believe in no matter where I am or who I'm working with or what story I'm telling: the story always tells us how it needs to be told. In [Ubuze Bam] I let the story speak to me. I would sit at rehearsals and say, “Chaps, tell me your stories. What do you want to say? What is the thing you feel that the world should know about you?” They would tell their stories, and we would talk about how to tell them onstage. Then I would give them a task to go in the corner for thirty minutes and then come perform the story. Then things come—you get signs. And from those signs, you take it from there. At the end of the day you're sitting with all these individual stories that just need to be combined and made into one thing. But [Ubuze Bam] is a different project because while it is a theatre show, it's much bigger than that because it speaks to people and their traumas. Of course, theatre does that, but these are people that society looks at differently. When people look at them, they don't see them as actors. They see them as ex-convicts. So how do you put them on stage so that people can just see them purely for who they are? You don't want people to come to the show and say, “Some things could have been done better if only they were trained actors.” You want people to receive what they are given without judgement.

Paul: What is your hope for South African theatre in ten years? What would you like to see then that you don't see now?

Thando: A space in theatre that is not divided. A space where we all get opportunities. A system that allows young people to come in and do what they want. Eyes and audiences that can take in different things. Theatre that pays.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here