Johanna

Facing Forward from Victim to Advocate

In 2007, Johanna Orozco made national news when she was shot in the face by her ex-boyfriend, Juan Ruiz, and miraculously survived the blast. Director and Playwright Tlaloc Rivas’ rendition of the story, is based on the Cleveland Plain Dealer’s award winning article series, “Facing Forward" by Rachel Dissell, and co-produced at Cleveland Public Theatre (CPT) with Teatro Publico de Cleveland an annex company of CPT launched in 2013. Teatro Publico is Cleveland’s first Latina/o acting troupe. Since its inception, the company has given a voice to a Cleveland population that is often unrecognized in the arts community. This world premiere bilingual play follows Johanna’s real life journey from abuse victim to survivor. The play features the stories of both Johanna’s survival and the advocacy of Rachel Dissell; a major player in speaking out against domestic violence in teenage relationships.

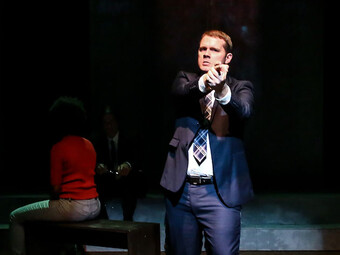

Johanna: Facing Forward gives a firsthand account of how easily abuse can manifest in relationships. Featuring a cast of newcomers from Teatro Publico’s growing company alongside local professionals, this ensemble tells a compelling tale of Johanna’s miraculous story. Stakes are high as the lights rise on Johanna (Tania Benites), standing center stage, begging her abuser to leave. Following a moment of silence, we hear a gunshot. Johanna falls slowly to the ground. Her Aunt rushes Johanna to the hospital while her distraught grandmother tries to hold her injured face together with a hand towel.

This resilient story sheds light on issues that are not commonly addressed. Abuse is far more common than it is credited and can exist anywhere, but it is all too often swept under the rug.

This is the jumping off point that leads the audience on a fast paced trek through the city of Cleveland. Beginning the night of the shooting; the play follows Johanna’s long recovery during her senior year of high school. Scene changes aided by the video projections of designer T. Paul Lowry quickly jump from past to present, and alternate from reality to dreamscapes, as flashback sequences unfold the story of Johanna’s relationship with Juan.

At first Johanna and Juan seem to have a typical teenage romance, full of adolescent emotional extremes. However, Juan’s feelings of insecurity and jealousy quickly morph into controlling and emotionally manipulative behavior. Their relationship soon exhibits a typical pattern of abuse—normalcy or calm, building tension, fights which lead to a major incident, physical violence, and eventually reconciliation followed by a honeymoon phase. The cycle repeats. The insidious nature of abuse is difficult to portray over the course of a two hour play; however Rivas manages to capture the formula with all its subtleties in the play’s first thirty minutes.

Using typical abuser tactics, Juan devalues Johanna’s self-worth; he criticizes her body and beauty, and convinces her that she is “nothing” without him. Johanna bears these hurtful words as hidden bruises. Juan’s abuse wears on Johanna—we witness her change from a happy, energetic, young woman to an exhausted, depressed teenager who isolates from her family and friends.

Like most victims of abuse, Johanna defends Juan’s behavior, despite knowing he is “sick.” She ignores the concerns of her family and friends, because she believes that she can help him get “better.” But Johanna discovers that she alone is not able to cure Juan of his abusive behavior. Instead he becomes more destructive and unstable, prompting Johanna to break up with him.

The real challenge is to teach another generation of artists what you know, what you’ve learned, yet allow them to make their own work. You have to be changed, be delighted by their vision, and then help them express it better.

The most dangerous time for a person is the moment they choose to leave their abuser. And as soon as Johanna leaves Juan, the danger is immediately apparent—Juan makes threatening phone calls, and stalks Johanna around her neighborhood. Next thing we know, Johanna is laying on a hospital bed answering the questions of a male police officer while simultaneously receiving a vaginal exam. She relates that Juan broke into her house during the night, held a knife to her throat, and sexually assaulted her. The uncomfortable scene of a vulnerable Johanna undergoing the rape-kit procedure needed for evidence, helps the audience to better understand the indirect shaming and humiliation that assault victims often experience. These interrogations often leave the victim feeling guilty, as if the attack was their own fault.

Although primarily focusing on abuse, Johanna: Facing Forward also sheds light on other women’s issues. We witness the prejudice that Rachel Dissell (Courtney Brown) faces as a female in the professional world of journalism. In multiple scenes with her editor, she is confronted with being “too emotionally involved in Johanna’s story,” and has a difficult time gaining her editor’s support on the piece. While writing the article, Rachel’s editor fights her every step of the way. However, Rachel is eventually congratulated for her convictions, only after The Dart Center of Journalism & Trauma recognizes her series. Rachel wins the 2008 Dart Award for excellence in covering traumatic events, and for sensitively and ethically reporting on trauma stories and their survivors.

In the second act, Rivas delves into the emotional toll of the abuse on both Johanna and her family. It opens with Johanna’s grandmother, praying in Spanish to the Virgin Mary, as her granddaughter undergoes a ten hour long reconstructive jaw surgery. After surgery, Johanna faces a difficult rehabilitation; she is overwhelmed by court dates, graduating high school on time, and interviews with the press. One of her great fears is that the media will use her story to paint the Latina/o community in a negative light. She stops all correspondence with Rachel. But as Johanna gains physical strength and emotional wellness she discovers the importance of being an advocate for herself and other victims of violence, and allows her story to be told. In the final moments of the play, the courageous Johanna faces Juan in court and gives a poetic personal statement to the judge:

All the things that once made me beautiful are gone. When I look into the mirror, I don’t see myself anymore, I see you...Take a good look at the scars on my face, because today I will disappear from your life. Now, from this day forward, I’m living my life free.

A journey worth seeing on stage, Johanna transforms from the powerless to the empowered over the course of the play. Her continued advocacy in teen violence issues has played a major role in the eventual change in Ohio protection laws to include minors. The power behind this play is the truth of its story. I remember when “that girl” from the “West side of town” was shot in the face. We shared the same graduation year, but at the time Johanna’s story had little to do with my own life. Today, however, I have to admit I am very affected by Johanna’s story; and Rivas’ retelling of it hits close to home for me. In recent years, I have seen abuse cycles first hand; as close female friends of mine remain in physically and emotionally abusive relationships.

This resilient story sheds light on issues that are not commonly addressed. Abuse is far more common than it is credited and can exist anywhere, but it is all too often swept under the rug. I believe dramaturg Megan Monaghan Rivas says it best in the playbill, when she states, “As powerful as Johanna’s story is, it’s the story of a solution that came together after an attack.” The lack of laws and awareness training for the prevention of teenage domestic violence, and general violence against women is a problem that existed long before Johanna and Juan. It is important to note that Johanna’s story is only known because she survived her assailant’s attack. Prior to Johanna’s unique tale of survival, many girls inside and outside of her community were not as lucky. Director Rivas shows us that violence against women is ever present even in 2015. In using Johanna’s story, Rivas raises awareness and reminds the audience that social change should happen before someone’s life is forever complicated or destroyed.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here