Making the Residency Work for You

Robert O’Hara, Playwright-in-Residence at Woolly Mammoth Theatre Company

Commons Producer Ronee Penoi interviews Robert O’Hara, Playwright-in-Residence at Woolly Mammoth Theatre Company, Washington, DC.

Ronee Penoi: You have a fruitful history with Woolly Mammoth both as a director and playwright. Your first encounter with Woolly was when Danai Gurira and Nikkole Salter’s play In the Continuum (which you directed) toured to Woolly. Then, your play Antebellum had its world premiere at Woolly, as did Bootycandy, which you also directed. In 2011 you became a Woolly Company Member. I’m curious about your relationship and synergy with Woolly as an artist prior to the residency.

Robert O’Hara: Howard [Shalwitz] and I have always been circling each other—he’s been a fan of my work since my first play. In terms of the first produced play of mine that Howard did, it was Antebellum. It was a wonderful experience. Immediately after that they asked me about something else. They had liked Bootycandy, which was a series of short pieces that I had written. They came upon this crazy idea about having it be a through-line play. It was literally twelve different short plays I had written over a decade that had nothing to do with each other. And so Howard and Miriam [Weisfeld] called me and said, “We really like Bootycandy, and we were wondering if there were certain characters that felt like they deserved to be dealt with more.” And I was like, “I have no idea what you’re talking about, these are twelve scenes that have nothing to do with each other.” But they said, “Well, take a look.” So I took a look and I was like “Oh, you’re right.” I rewrote it, but what they did was amazing. They committed to doing a production a year out and said: whatever you write we’ll produce at the end of the season. So we did Bootycandy and then they called and they asked me if I wanted to be a company member. And at the same time they said, “We would love to commission you for a new play.” They were doing this Free the Beast campaign. So they said, “We want you to be the first playwright who is a company member and the first Free the Beast commission.” That became Zombie: The American. Then they asked me to put forward some names for this Mellon thing. And I said, “What is it?” “It’s the first of its kind, it’s going to be three years, full salary, and whatever.” And I’m like “... how about me?”

Ronee: That’s great!

Robert: So that began this sort of crazy journey with Mellon and the Woolly. I’ve been a director here, I’ve been a writer here, I’ve written and directed my work, I’ve allowed other people to direct my work, and I’ve just directed other people’s work. And I’m directing another Mellon grantee, Peter Nachtrieb. It’s like a second home. No one really does what Woolly does and no one would let me do what I do but Woolly. And encourage me to do what I do but Woolly. So it’s absolutely an artistic home for me.

Ronee: You’ve had a fantastic relationship with Woolly for some time, but I remember you had concerns about the residency going in. What were they?

Robert: My main concern was that I had no intention of moving to DC. I’m in a long-term relationship and I just bought a condo in Brooklyn, and I was not making my partner move to DC, and I’m certainly not going to move to DC for three years and then get up and go somewhere else. And also I’m a director. And so my concerns were how much time would I have to be in residency in DC and will they allow me to continue my directing career. Otherwise, I wouldn’t do it. So we structured the residency around who I am. And quite frankly, one doesn’t have to be in residency to write a play. This is not solely about playwriting, this is about embedding the playwright in the building.

It turns out that Howard is very open about allowing people to have new ideas about things. And he has been here for thirty-five years, so there’s no marking his territory. There is no territory but Howard Shalwitz territory. Usually playwrights are not on the staff of the building. I wanted them to know that I wasn’t just going to be sitting around and being polite and that I would actually speak my mind and be who I am. And my job ends in two years now, so why not speak my mind?

I wanted to actually be active in certain things and there were certain things I didn’t want to do. I’m not going to be that “every man,” be involved in every aspect of the theatre. I write for a living, so I don’t like to have to write a bunch of stuff for a grant or what have you. My work is put in front of people all the time, so I’m not someone that wants to go in front of communities and be in front of people. Let my work do that. So it was important that they knew that the things I wanted to do I wanted to do, and the things I didn’t want to do I didn’t want to do. And we made that very clear.

My work is put in front of people all the time, so I’m not someone that wants to go in front of communities and be in front of people. Let my work do that.

Ronee: Could you talk a bit more about some of the many hats you have been wearing during your residency so far, and what some of the highlights have been?

Robert: Right when I started there was this need to make a season announcement. For some reason Howard said, “Robert should do it!” And I’m like, “What are you talking about?” And he said, “You should produce the whole thing and put it together and make an evening of it. Make it something different than what we normally do.”

In order to produce anything in the building you have to know most of the people that are involved in the day to day in order to get things done. It was like really being thrown in the mix immediately. And it was something that needed to be exciting. So I produced the season launch presentation. I got all the people, all the playwrights that could to come in, and came up with a script, and got a host, and got actors to present scenes from the plays—it was a lot of logistics. It was a little bit risqué, because that’s who I am, but also it was different than just the artistic director up on stage saying this is what we’re doing next season. There was a lot of tongue and cheek and that was exciting and fun, and immediately when it was done they were like, “So, you’re going to do this next year” and I was like, “Uh, no.”

I also was the sort of in-house line producer, if you will, for Appropriate by Branden Jacobs-Jenkins. I knew the director and the playwright and I had a relationship with them both. It was a play that was in flux when it was here, because it was having several different productions in the same season, so the playwright was writing for various productions, two of which, including our own, that Liesl [Tommy] would be directing. And it was a big play. And it was a play written with clear relationships to older plays, so there was a lot going on, and a lot of different personalities to handle. So Howard made this part of my residency, that I would take up the artistic director role for at least one project every season. So Appropriate was it, from production meetings, to previews, and through opening. And it was quite wonderful. Also going to Humana last year and going to the TCG conference last year as a representative of Woolly was quite exciting , and I was a representative to NNPN for Woolly.

Ronee: You’re really embedded in the team. It’s not that you’re just part of these conversations, there’s an incredible amount of trust, respect, and leadership too. Could you speak a little about what it’s like to lead and be embedded in an institutional framework as opposed to your personal framework as an artist.

Robert: One of the things that I was not used to was the whole staff meeting. Because I’m on the senior staff I also meet with the senior staff. In my own personal leadership when we have a staff meeting, I’m the leader in a way, even if it’s a production meeting, someone may be running it, but ultimately the decisions begin and end with what I’m interested in or not. So most personalities have to figure out how to work with me. But when you’re in an institution there are regular meetings and these meetings may have to do with things that are not directly or personally involved with your day to day life. When you’re directing people are expecting you to have an opinion about everything. I think that in institutional leadership, I’ve learned that you’re the person to listen to other people’s suggestions and amalgamate them.

Ronee: Let’s turn to season planning. You talked in a macro way about what leadership means in the institutional framework. In season planning there’s an added artistic dimension too. There are also a lot of artists Woolly is getting to know better and deeper through you. But your role in that is different than it would be just as an artist saying, “Hey! Here’s my friend who wrote a play.”

Robert: Right. There are certain plays that I like that I don’t think should be done at Woolly, or don’t think are right for Woolly. And there are certain plays that I don’t like, and I do think would be good for Woolly, good for other people to see. Some plays I want to direct, some plays I wish I had written, some plays I am writing, so all those things are wrapped up in season planning.

Ronee: Do you think that your experience of the residency has changed the way that you write and direct with Woolly or other theatres?

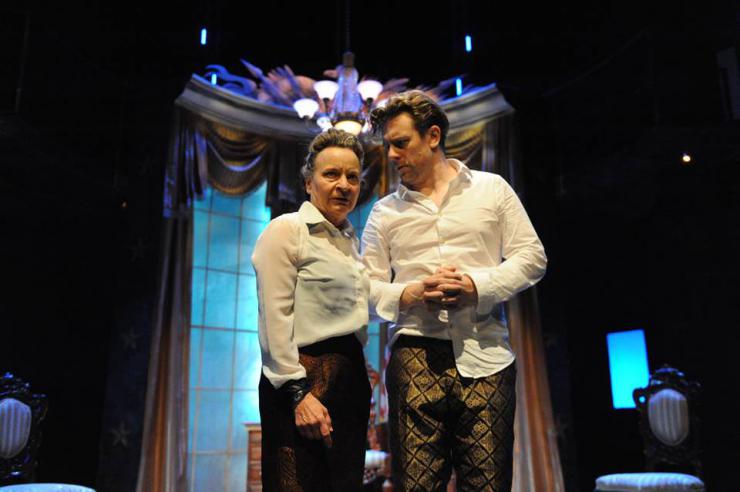

Robert: It’s been interesting because we’re doing a play called Marie Antoinette by David Adjmi. It was a play that I really wanted to direct at Woolly. But I’m directing Peter Sinn Nachtrieb’s play Totalitarians at the end of this season. And we’re opening with David’s play, so I can’t actually direct the last play and expect to be offered to direct the opening play. So Steppenwolf calls and says we would love for you to direct something here, what do you want to direct? After a lot of back and forth, I say, Marie Antoinette. So, they started reading Marie Antoinette. Being in season planning has allowed me to actually read and also be aware of what’s out there. I see a lot of plays. What I don’t see are the plays that are not done. So although David Adjmi’s play had been done in New York, there are a ton of other plays that now I am aware of. I have what’s in the pipeline in front of me. Any play that anyone has written that has a significant backing in terms of agency or reputation or talent, we have and will read. In terms of my own writing, plays are exciting to me and engage my own writing. It doesn’t change what I’m going to write, but it does allow me to see what the trends are in people’s writing and what’s lacking—and also what’s being done to death.

Ronee: Do you think your process of working on Zombie or Totalitarians in particular has been any different because of the residency?

Robert: It’s been different in that I’m in residence.

Ronee: Right, you’re here!

Robert: Right! So I have to find time to write. I can’t write in these offices. So what has to happen is I have to say I’m not coming to Woolly, I’m going to stay in New York and write, and that is going to be part of my residency. I’m going to go and scout shows in the evening, which I do all the time.

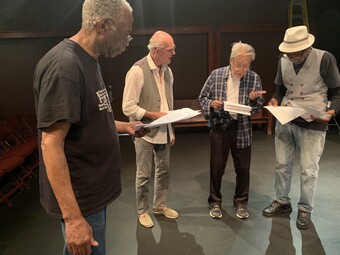

And now notes are given to me by people who I’ve sat in a room with for a year talking about other people’s plays. One of the joys is that they’re not strangers. We’re not afraid to just get to the point and be honest with each other, we’re not walking around ego and they’re not afraid that I’m going to fall apart or think that they’re overreaching. And this is a commission, so it’s not only a play that I’ve written, but it’s a play they’re paying for and that they have committed to doing, which so rarely happens. It rarely happens that a theatre commissions you and they do the play. Usually what happens is they commission you and then they give you all these hoops to jump through and then they decide not to do the play. But regardless, you have to jump through hoops. I don’t have to jump through any hoops here, the hoops have been removed—they’re doing this play. Whatever I decide to do, it will end up on that stage. And that’s a liberating feeling for a playwright.

Ronee: It’s been kind of an interesting pro that you haven’t been living here in DC full time. Not just for you, but for Woolly. I think it’s a bright spot for other people to potentially think about. You think “in residence” and it’s loaded with “you are there always,” but this part-time model has been tremendously successful.

Robert: What’s exciting about my residency is that I’m here when I need to be here. I’m never here just hanging out because I’m in residence. There are particular projects in which I’m involved, and I organize my time to be here for those projects. It also tells the building that I’m an artist, I’m not an administrator. Even though I’m in an administrative position, I’m an artist. There’s just something exciting about going into a building in which creative work is being done. And the people acknowledge you as a creative force in the building. As opposed to most of the time as an artist people go in buildings hoping that someone will give us a chance...

Ronee: —or permission—

Robert: —or permission to be an artist. And I don’t have to walk into Woolly and ask for permission to be who I am. That’s exciting.

Ronee: If someone were considering a residency, what would you want them to know or what would be important for them to think about before diving in?

Robert: You have to think about the flexibility of the residency. And in thinking about that flexibility, think about the goals of the residency. This is not a writing residency. I’m going to be here for three years and write this many plays and then you either do them or not do them. It’s “I’m going to be involved in your institution in a creative way and in an administrative way and I’m going to be who I am and you use me as best you can, because I’m certainly going to use you as best I can to grow as an artist and as an individual.”

Decide whether it is a city and an institution that you actually want to be inside of. If I was in an institution in which my engagement with Howard was limited or I was basically put in a department and kept in that department, I’d have a problem with that. If the artistic director is on the other side of the building in a suite of rooms having private meetings with people, then that says something about what your experience will be. Take a look at the architecture of the actual building that you’re supposed to be in residence and see if that is something you want to be in residence with. It’s going to be a place where you’re going to live mentally and emotionally. Then the length of the residency is important. Theatre seasons don’t happen in a year. Our seasons happen over two years, fall to spring. I would say that residencies should happen over a season as opposed to a year. And I think also, being brutally honest, nothing is worse than being in a residency for three years and saying to yourself what did I think I was doing? Why am I still here? How can I get out of this? Leave time for yourself as an artist, because you’re not going to come to this building and write, you’re not going to have privacy. You want to build into your residency space for you to maintain yourself as an artist; you just don’t disappear into a room or into a space or to a residency—you come back out—and you’re like, whoa, what have I done.

Ronee: You’ve thrown in sharp focus how rare it is to find two people—in this case, you and Howard—who are willing to be honest and specific about what will work for both of you.

You want to build into your residency space for you to maintain yourself as an artist; you just don’t disappear into a room or into a space or to a residency—you come back out—and you’re like, whoa, what have I done.

Robert: When you’re negotiating something you have to be prepared to leave the room, you have to have a point where you go, well, if I don’t get this, than I can’t do this. Otherwise, you’re not really doing it for yourself, and you’re going to make yourself miserable. My host city would be New York, but there’s no theatre in New York that I have the same sort of relationship that I do with Woolly, who have said to me twice now, we’re going to do whatever you write in this slot. That goes a long way for an artist. Especially at the age I’m at. I can’t reintroduce myself to you every time I meet you. And at Woolly I don’t have to.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here