How R.Evolución Latina is Reinventing the Bard

I remember it clearly: I was in the fourth grade and my literature teacher had just assigned us Hamlet. With no previous knowledge of the Bard’s work, we were asked to read the play and prepare for an exam. Even though I knew what the individual words meant, I couldn’t make sense of anything in the tale of the tragic Danish prince because the structure of the sentences seemed almost extraterrestrial. I made my way through the play over a few weeks, knowing only that I knew nothing about what I’d read. Much to my surprise, someone suggested that Hamlet was nothing if not a more violent, serious version of The Lion King, and it was only then that things clicked.

My experience of being force-fed Shakespeare because it was the “right thing” to teach isn’t unique. In fact, many people distance themselves from his plays because of the resentment they harbor from the way in which Shakespeare is taught in elementary or high school. We all reach a point where we know of Shakespeare, rather than know Shakespeare. When Luis Salgado, founder of R.Evolución Latina, teamed up with collaborators from the Public Theater, SITI Company, and Pregones Theater/PRTT, for To Be or Not to Be...A Shakespearean Experience, he knew he wanted to provide participants with a different way of learning the Bard’s work. “I studied Romeo and Juliet when I was in school,” explains Salgado, “and English wasn’t as easy for me. I remember my teacher made me read it out loud and it was so scary to read words I didn’t understand.”

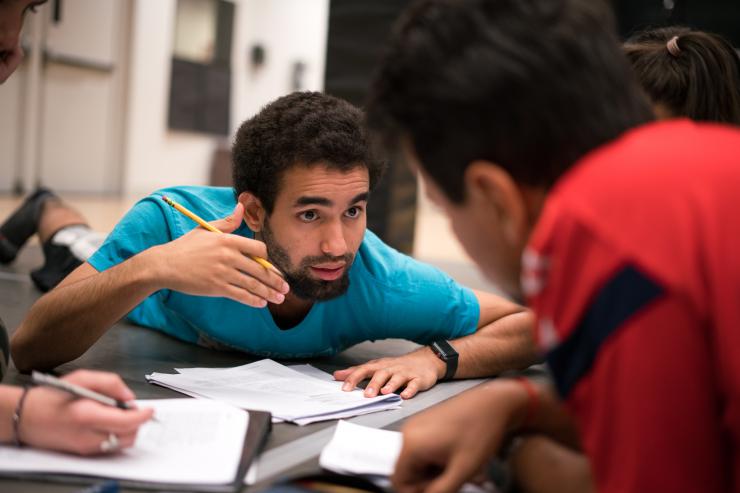

This didn’t prevent Salgado from going into the arts, and as a director/choreographer/performer he has worked to create defined paths for future Latinx performers. With To Be or Not to Be, Salgado wanted to celebrate Latinx artists through the words of Shakespeare, by devising a theatrical piece that filtered the Bard’s works through music, dance, and acting. For his ensemble, Salgado recruited a multicultural cast that featured established performers along with newcomers from all over Latin America, who came to New York City on a scholarship to be a part of the workshop. After a few weeks of rehearsals, where the artists each learned new ways of exploring Shakespeare’s words, working with choreographers, directors, and performance instructors, they put on a show that ran for a few performances in the spring of 2018 at the Harlem School of the Arts. The show incorporated dance, sonnets, and songs, and was performed in Spanish, English, and French, among other languages. Salgado’s purpose was to highlight Latinx talent while creating a piece that celebrates our influence in the United States.

For performer Ismael Castillo, the workshop was almost utopian. “This show is an example of how the world could be. There are people from all over, and we’re getting together to create a piece of art,” Castillo says. The twenty-two year old first encountered Shakespeare in high school and liked how he used words. “I wasn’t very good with schoolwork back then,” Castillo adds, laughing, but in the R.Evolución Latina workshop he discovered how he could use the Bard as a tool for his own work. Castillo is a lyricist, and even though he’s not as comfortable in Spanish as he is in English, he saw how Shakespeare’s words elicit different emotions depending on the language. “The contrast is really interesting,” he explains. “Shakespeare by itself is its own language, so it’s wonderful to see people say his words in their own languages.”

We all reach a point where we know of Shakespeare, rather than know Shakespeare.

In the workshop, Salgado emphasized how language affects the way Shakespeare is perceived. “[Shakespeare] seems [to be] a very high bar in terms of the language and meaning of the words, so there’s a misconception that his plays have to be done in a certain way,” Salgado says. “What works with our students is showing them how to use Shakespeare as a tool, how to use verbs, what to do with iambic pentameter. And, most of all, teaching them to get close to Shakespeare, giving them ownership over his work.” Salgado confesses the first time he truly understood the magnitude of the Bard was when he saw Baz Luhrmann’s modern-day adaptation of Romeo and Juliet, which showed him not to be afraid of Shakespearean language.

“Fear” is a word that shows up often in my conversations with several of the participants in the workshop, who often associate “not being good enough” with who they think can or should do Shakespearean works. Through techniques including the Suzuki acting method, the instructors hoped students would be able to connect to the text using their own life experience. Eduardo Uribe, a Colombian dancer, explains, “One of the things [we did was] a contemporary dance piece with Gabriela García, which [had] one of the sonnets recited over a melody.” On top of the melody, García had her students memorize spoken dialogues as they moved, which made it easier for dancers to retain the text. For Uribe, who was familiar with using muscle memory to learn steps, memorizing the Shakespearean texts was a breeze, as “each step [was] linked to a word or a phrase in the sonnet.” Uribe also adds: “I was surprised to realize how much a dancer could learn from Shakespeare, especially because now I’m noticing how many musicals are based on his work. Without us realizing it, we watch Shakespeare’s influence all over. There’s no way of hiding from him.”

Adriana Coronado also comes from a dance background, which means she hadn’t had direct contact with Shakespearean plays. “The complexity and rhythm of Shakespeare’s words is a great food for movement,” she explains.

His words inspire movement naturally. I’m a contemporary dancer, so I [was] able to connect to the depth of his text through movement. It’s harder to draw complex movements from simple texts, so Shakespeare [gave us] a treasure chest of inspiration. In modern dance we learn about Martha Graham and José Limón, who draw movement from within, and there are Shakespearean texts that help you precisely connect with this visceral feeling.

For performer Krystal Pou, who comes from the Dominican Republic, Shakespeare revealed himself through music. “You need to find the rhythm in the words,” she suggests. “I [assigned] a beat to a line, and when I [walked] down the street I [remembered] the beat, and the words [came] along. Or you [could] also create melodies and assign them to words, that way whenever you think of the melody the words appear.” Castillo similarly used words to grasp the depth of the sonnets. “As a writer, it helped me to sit and break down the words. Shakespeare is a lot—the page looks like a lot of text—but in the process of writing you get to see each word individually, rather than a piece in a huge page of text,” he explains with excitement. “There are words in Henry V where you can see how he uses a single syllable to attack what comes next, you get that connection to his words just by writing them.”

‘Without us realizing it, we watch Shakespeare’s influence all over. There’s no way of hiding from him.’—Eduardo Uribe

For Igor Correa, who hails from Venezuela, a key to unlocking the power of the texts was to turn them into a game. “Imagine going to a party and setting a rule that everyone has to speak Spanish only,” he explains. “You can try that with Shakespeare too. Repeat the monologues one hundred times if you must, talk to other cast members in iambic pentameter.... Once you learn the rules you want to play it all the time.”

Salgado recalls how his singing teacher used to tell him to “see more,” and he followed her advice by taking in as much theatre as he could whenever he traveled. In London he saw a circus version of Romeo and Juliet that involved acrobats and trapeze artists, as well as a version of Macbeth that he recalls as “taking place right in hell.” The importance of mentorship is at the center of R.Evolucion Latina’s mission, especially since many of the students later return to their home countries and are able to share what they learned with their classmates back home.

Even those who are a bit skeptical of Shakespeare—like Uribe, who states that he respects him but doesn’t like him—have found important tools in the workshop. “The way in which we work with the text here has made Shakespeare feel more urgent to me,” Uribe says. “I used to think it was very boring material, but Luis has taught me how to love the text because I get to experience it through things I’m passionate about like singing and dancing.”

For one of the performers, the workshop arrived at a truly perfect time. Pou was at an existential crossroads. “One Monday I was feeling quite hopeless about my career, so I decided to skip dance class and seek solace in a warm plate of mofongo at a local restaurant,” she explained. “I thought mofongo and a beer would help me deal with my sadness.” To her surprise, Salgado was sitting at the table next to hers. She recognized him because he knew her sister—having taught her at a workshop in the past—so Pou approached him, telling him that seeing him there filled her with hope. Salgado asked her what she was interested in working on, and if she had a Shakespeare monologue ready to go. Pou went home, taped her monologue, and sent it to him, and she made it into the program. While Pou used to be self-conscious about her accent, the workshop helped her realize that language shouldn’t be a barrier. “I don’t feel lost anymore,” she adds. “I now know who I am as an artist.”

The performances were warmly received by audiences who praised them for being reminders that the United States is a country where walls should be torn, not put up. They were Shakespeare done in an innovative way, by a group of talented performers, some of whom were making their professional debut. Judging from the audiences’ reaction after the show, the experience might even have been revelatory for some; leaving the theatre after a performance, a little boy made his way to the exit reciting “ser o no ser”—“to be or not to be” en español.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here