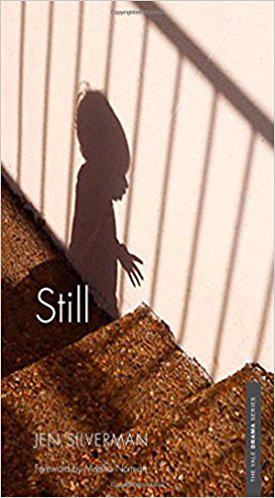

Still

A Conversation About Collaboration

In the spring of 2010, I was in my second year of an MFA at the Iowa Playwrights Workshop when Loyce Arthur, Head of Design, approached me and said, rather mysteriously, “There’s someone I’d like you to meet. She has a story.” Saying to a playwright that someone “has a story” is like saying to a junkie that someone has a mountain of refined crack cocaine, so within a few days, Lisa Heineman and I were sitting across from each other in the downtown Java House. Lisa spoke very clearly and plainly. My first impression of her was of a kind of fearlessness. She told me that she had recently had a stillbirth, that her dead son was nicknamed Thor, that her experience had underscored for her how invisible stillborn babies are to a culture that is already squeamish about death. She was sick of the silence and was writing a memoir, but theater had caught her eye. What she wanted was to see stillbirth and its ramifications explored on a stage. At first I thought Lisa was asking for my suggestions on how to write a play. At some point, I realized that we were discussing my writing a play. What followed was a collaboration that lasted two years, became a friendship, saw the creation of my play Still, and reached a culmination of sorts in April, when Lisa saw Still read in front of an audience for the first time in Iowa City. In the aftermath, Lisa and I take a moment to ask each other questions about the process of our collaboration—what we expected, what we found, and what was made.

JEN SILVERMAN: Can you talk about your stillbirth and your relationship with Thor?

LISA HENIEMAN: My stillbirth came as a complete surprise—everything was fine, it was a full-term healthy pregnancy, and then I just had one of those disastrous deliveries. But the fact was, this baby was still my child, and I needed to build a relationship with him. With the support of the world’s most amazing funeral director, I visited Thor every day at the funeral home and brought him home twice for overnight stays. My partner and I carried him in a sling, read to him, and rubbed lotion into his face. We introduced him to our home, our neighborhood, and the site where he’d be buried. We prepared him to go out into the world he’d inhabit, and we prepared ourselves to send him off. That’s what you do with your kids: you prepare them to go out into their world, and you prepare yourselves to let them go. And then we said goodbye.

Photo by Amazon.

LISA: What drew you to the idea of writing a play drawing from my experience of stillbirth?

JEN: I was terrified of writing a play about stillbirth. If someone had asked me: “Jen, what do you not want to write about today,” I might have said stillbirth. I had no experience with trying to have a child, let alone losing one. But I was drawn to you—how fiercely unapologetic you were about your grief, and your irreverent, dark sense of humor that kept surfacing despite the tragic nature of our conversation. I remember when you told me that you put Thor in a sling under your jacket and took him on a walk around your neighborhood. That was when I knew I had to write the play. I was so moved by your refusal to accept a set of norms for how to grieve, by the courage it must have taken to forge your own set of norms. And it made me think of Thor as a person who died, instead of as an event that didn’t happen, which was your point all along, I think.

It was less of a clearly reasoned decision and more of an organic happening. I thought that to write a play that reflected even a part of the intensity of your experience, the characters had to exist in moments of extremity, at places of extremity. The giant dead baby named Constantinople, the dominatrix who becomes his friend, the midwife whose life has turned into a search for redemption, the mother who is caught between her anger at the injustice of the universe, and her love for Constantinople, dead or not—these, to me, felt like truthful representations of the way the world becomes distorted and lines thinned in moments of extreme emotion.

JEN: Why were you interested in theatre as a way to explore this experience?

LISA: I was open to anything that would extend my time with Thor and confirm his existence to the wider world—and theater fell into my lap. Once Loyce suggested it, and especially once I started talking to you, I realized theater would allow Thor to come to life in a way that was very different than my own memoir writing would allow. You learned about my experience in two ways: first in conversation with me, then months later by reading drafts of materials that would eventually go into my book.

LISA: Why did you approach this in the way you did?

JEN: I think the very nature of theater is that information is contained in more than words. I talked to you for months without reading your writing, because I was listening for more than just the facts of the stillbirth. I was listening to your gestures, your pauses, the moments when you rephrased something or corrected yourself. Your tone, and moments in which it changed, told me everything. I had to make sure that I would not read your work as a guideline for my work—I wanted our live interactions to be my guideline.

LISA: What other kinds of collaboration have you done? How was our experience different?

JEN: The Iowa Playwrights Workshop is an amazing program because of its focus on collaboration through production. And I’m currently working on a two-man play that I wrote for identical twin actors Jake and Jeffrey Manabat, so the dialogue is specifically tailored to their rhythms as actors. But collaborating with you was unlike anything I’d ever tried before. Usually there are very clear roles: directors direct, actors act. With Still, our collaboration was intimate and fluid from the start—we were talking about your child’s death, not about where to hang the lights. I was asking you questions but, unlike the one-sided nature of an interview, you were asking me questions too. Both of us were figuring out together what our roles were, as opposed to showing up knowing the parameters. I think I only felt uncertainty about my role when I was writing the first draft and realizing that it was not at all an adaptation of your story. You had told me a story of a woman in a strong committed relationship who carried and lost a baby, and was grieving. I was writing a play about a giant dead baby who was wandering around the world learning about life. Oh yeah, and his best friend was a queer dominatrix. I remember at one point I thought, “Lisa is never going to talk to me again.” I had this fear that, as your collaborator, I had failed you, because my play—while rooted in the darkness, the irreverent humor, the strength I had heard in your story—was not your story.

JEN: Did you have any fears about giving me permission to write something that wasn't an adaptation of your story?

LISA: I didn’t feel like I needed to have you tell my story, at least not in a literal representational sense. Having read and seen your work, I knew you were going to go off in your own direction even before you asked me if it was OK. I just couldn’t see you settling for someone else’s imagination. Or for realism. But reading your work also told me that you weren’t going to do violence to my experience, for example by sentimentalizing it—if anything let me know that I could trust you, it was reading your work. Really, I was excited about having you come up with your own piece. First of all, there’s the wonder of seeing something new evolve. But in addition, having you create a completely different piece had the effect of giving Thor a bigger footprint on the world, which felt like a satisfying act of defiance for me.

LISA: What made you decide to write your own story rather than try to adapt mine?

JEN: It was less of a clearly reasoned decision and more of an organic happening. I thought that to write a play that reflected even a part of the intensity of your experience, the characters had to exist in moments of extremity, at places of extremity. The giant dead baby named Constantinople, the dominatrix who becomes his friend, the midwife whose life has turned into a search for redemption, the mother who is caught between her anger at the injustice of the universe, and her love for Constantinople, dead or not—these, to me, felt like truthful representations of the way the world becomes distorted and lines thinned in moments of extreme emotion. I found that in order to be truthful to tone, I could not be factual about event. I’ve never thought of myself as either a journalist or a documentary theater-maker, so I was just as happy to sacrifice fact for a different kind of integrity, particularly once I saw you were fine with it.

JEN: What was it like for you to be in the rehearsal room for the Iowa reading of Still?

LISA: Since I’m not a theater person, I’d never given much thought to what goes into a production, and particularly the ways everyone involved engages with the material—playwright, director, actors, and so on. For naïve me, it was a revelation that a play doesn’t just reach an audience; it also reaches the people involved in the production. So it was pretty wonderful to see even this small group really grapple with the issues the play raises. I cried during every single rehearsal.

JEN: And what was it like for you to see the play presented in front of an audience?

LISA: Since it was on my home turf, many members of the audience were friends. That was very moving, but it also complicated matters: I wasn’t just watching the play & watching the audience’s reaction, I was also being watched by people who probably have more at stake in my well-being than in the play’s success. If I hadn’t realized it by then, at that point I definitely understood one of the advantages to your having created your own work: no one was going to confuse the bereaved mother on stage with me, even if they might speculate about what parts of her character were based on me. But aside from all that, it was almost like a moment of farewell: the play was standing on its own feet, it had its own power, and after Iowa it would go on to a full life elsewhere. Maybe I’ll be lucky enough to cross paths with it once in a while, but it’ll live most of its life and make most of its mark away from me, and most of what it accomplishes will remain completely unknown to me. I know I’ve used the parenthood analogy before, but here it is again. It’s bittersweet not to be fully part of its world any more, but it’s also exactly what’s supposed to happen, and it’s lovely because it means you did your job right.

LISA: What kinds of hopes did you have for this sort of collaboration?

JEN: My biggest hope was that you would feel like your voice had been heard. That you would see Constantinople come to life, and see in him a validation of Thor’s existence, and an imagining of what that life—although brief—could have looked like: the wonder in it, an appreciation of beauty made all the greater because there was so little time. The idea of writing that play was terrifying, and so of course it was exciting, but in the end I took it on because your story—and your honesty in telling it—touched me so deeply. I wanted to give you back something that would have value to you. After the reading in Iowa, you and your partner Glenn told me individually how much it mattered to see the audience hearing, acknowledging, and rooting for Constantinople. You both told me that it had been difficult to watch, but also that you had felt a certain freedom—like your child was going out into the world, the way he should have. To hear you say that was like a dream. I left Iowa City thinking that it didn’t matter whatever happened next for the play—in some ways, my biggest hope had already come true.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here

What an inspiring model for a piece which evolves from a deeply personal place not to documentary-theater but to a more abstract place of essence through the careful and thoughtful transfer of story ... Bravo!

What a beautiful, poignant and provocative collaboration. Thanks for sharing.

This is such a rare and beautiful story. It calls to mind Anne Bogart's idea that if theatre were a verb it would be "to remember" tho in this case I think of the verb "to incarnate"