Undocumented Stories Have Always Mattered / Las Historias Sobre Los Indocumentados Siempre Han Importado

What happens when the stories you tell suddenly become politically relevant to the masses? When President Donald Trump announced that his administration would be ending the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) Program in March 2018, undocumented people were thrust into the national spotlight. While political pundits expounded on the reactions to the announcement, people without documentation were routinely left out of the conversation, or were stereotyped as either "good" or "bad" immigrants. Actor and writer Alex Alpharaoh (Los Angeles, CA) who was born in Guatemala and is undocumented, writer and director David Lozano (Dallas, TX) who was born in the US and is a US citizen, and playwright Karen Zacarías (Washington, DC) who was born in Mexico, and only recently was granted US citizenship, talk about their work that centers the stories of undocumented people, the activists who fight with and for them, the complicated nature of this flawed legislation, and how it feels to suddenly have their work be more relevant than ever before.

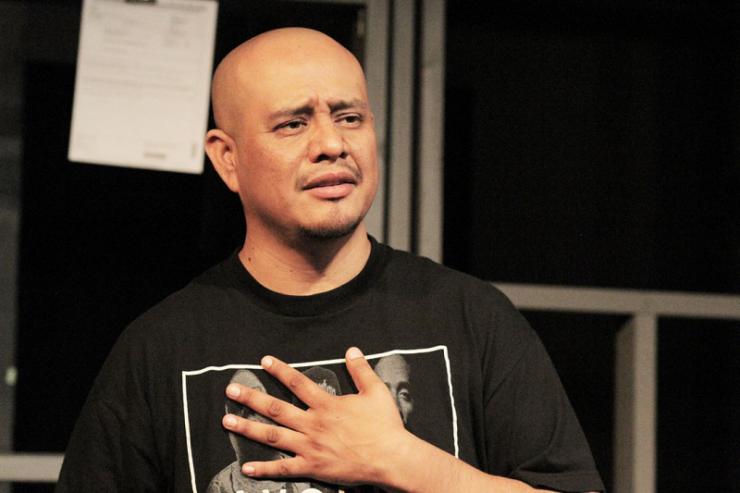

Alex: My solo show Wet: A DACAmented Journey chronicles my life, my personal journey as an undocumented American who has been in the US since I was three months old. I'm one of the older DACA recipients—I just met the deadline by a few months. It chronicles the story of what I've had to do in order to try to adjust my status in the country, and to gain legal residency after the 45th administration came into power and began to put systems in place that will attempt to deport the more than 11 million undocumented people in the country, including DACA recipients that are now at risk because the DACA program has been rescinded.

Karen: Your play needs to go everywhere, that’s for sure.

Alex: Well, thank you. We just closed the initial run at Ensemble Studio Theater Los Angeles, we are bringing it back for a very limited engagement in October, and then it goes to 2017 Encuentro de las Américas International Theatre Festival in November.

Karen: I am sorry it's so relevant, but I can't think of a more powerful statement. I want every congressman and woman to see your play.

Alex: Thank you, yes. I feel conflicted about it because I am getting a lot of wonderful recognition—people are really connecting with the story, and it's educating people who may not know what it's like to be an undocumented American—but then at the same time the situation is unfair. One hundred percent of DACA recipients have clean criminal records, and most of them are stand up citizens, and to be categorized with drug dealers and thieves and murderers and people who come here to steal jobs and identities is kind of the rhetoric I'm trying to help change. I'm sure that David’s piece, Deferred Action, and your work is shedding light on that as well.

Karen: Absolutely. I have a different immigration story—I actually became a US citizen on Friday, after a long journey. I was one of the first people to get to see Trump's video “Welcome to Our New Citizens” and, let me tell you, it was very non-welcoming. This is a tough time to be an immigrant.

I came here as a kid with a Visa through my father's work, and then the US government at one point said, “We want to keep your dad and your mom here, but your time is up. We know you've grown up here, all your friends are here, your family's here, but you alone need to go back.” And I was like, “To whom, to what, to where? This is where I grew up. Kids go where their parents take them."

I had the fortunate opportunity of adapting a book called Just Like Us written by Helen Thorpe for the Denver Center. It chronicles the life of four girls who are all born in Mexico, but two of them have documents and the other two don't. They're all straight-A students and leaders in their school, but it addresses how the two girls who have documents have opportunities that the two undocumented women don’t. The play chronicles these four young women against the backdrops of mounting anti-immigration due to 9/11 and the murder of a police officer in Denver by an undocumented young man. It touches on all the kinds of nuances and tries to dispel some of the myths that you brought up, Alex—DACA kids are good students, they're committed to being in the community, they don't have a police record, they have so much to bring to the American citizenry. It seems short-sided, economically stupid, and morally wrong to rescind this promise that we've made to young people who really are American in every single way except on paper.

David: I've been in contact with Dreamers in Dallas since I returned to Cara Mía Theatre in 2009, and our first play that we produced was a political play about teenagers in Crystal City, Texas. First they led a walkout that lasted several months in protest against punishment for speaking Spanish, and in favor of transforming their curricula into one that reflected the Mexican and Mexican American experience, which was the majority of the population of Crystal City. And then the students were inspired to encourage their parents to run for office, and the students canvassed for their parents, and the Mexican-Americans in that town ended up taking over the school district and the city council. The Dreamers were really attracted to this story, and they became supporters of Cara Mía. I became close friends with the founder of the North Texas Dream Team, Ramiro Luna. I was struck by the difficult position that he was in, as someone who worked with politicians and elected officials, but who was always challenging them. When the DREAM Act didn't pass in 2010, he was crushed. He was a very bold activist who was often creating political theatre and guerrilla theatre—spectacles to draw media attention, and attention to hypocritical politicians. This tension between working with Democratic politicians while also challenging others in very bold ways really impacted me.

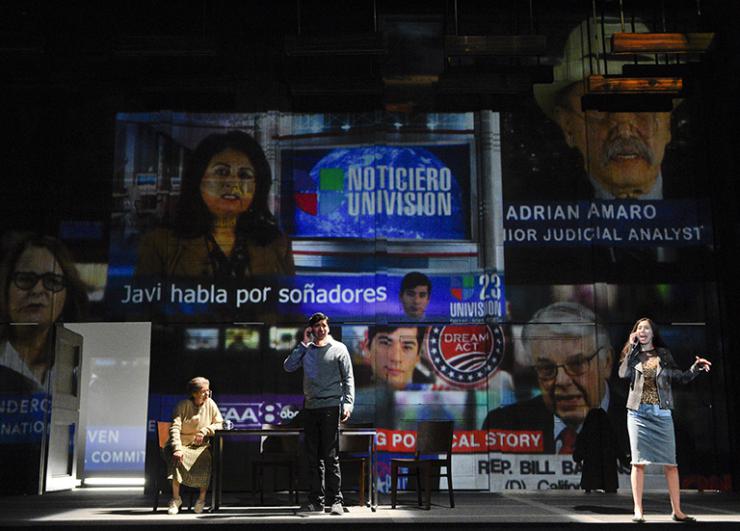

That became the inspiration for Deferred Action, and in many ways the title of the play refers to the deferred action of our elected officials who have not passed immigration reform. The characters are Ramiro and his close collaborator Marco Malagon and another friend of ours. When Lee Trull and I decided to work together on this play, which was developed at the Dallas Theater Center as a co-production with Cara Mía, we interviewed the three of them over the course of two to three years, and we developed a story inspired by this conundrum that they live in.

The play is about two Texas politicians who have the possibility of becoming the nominated Presidential candidates. One is a Latina Democrat and the other is a Tea Party Republican. Over the course of the play, the protagonist expresses his frustration with the Latina Democrat who isn't vocal about immigration reform. The Tea Party candidate starts out with bellicose statements about immigrants, but he ends up having a dream that changes his opinion overnight, and he decides to put down a bill for full immigration reform and run for President. So the Dreamers are torn by who to support.

Alex: It's interesting that you're touching on all of these different subjects and delicate contexts—that's very important for people to see. One thing that I always seem to be getting into conversations about these days is the term "Dreamer." As an undocumented individual myself, it is difficult for me to associate with the term Dreamer, and I think that's growing within the undocumented community, simply because it's a failed legislation. It‘s a legislation that's let down the community for more than a decade now. If nothing happens in the next couple of years, it will be twenty years that they have been trying to pass legislation that has failed for some reason or another. Somebody once said, “You are a Dreamer, so you have hope!” And I said, “No, I'm a realist.” Having dreams has nothing to do with it.

Karen: I know a lot of people who are undocumented, a lot of my students are, but they are not officially Dreamers. There is a whole other group of young people who are not even part of that specific program that you need to sign up for. The term Dreamers evokes a kind of hope and warmth that is very opposite to the reality of what is going on.

Alex: It hurts that for many years we have put faith into the hands of these elected representatives.

David: This iteration of our production is actually about how our community of young folks who are changing the narrative, and changing the vocabulary. One cast member said in a talkback the other day that we are correcting the narratives that were created early on, which is, “We are great students, we are well behaved, we are educated and professional.” What that did was alienate those who may not be great students, who may not be well behaved. Even worse, the idea of being brought here by parents without our permission was criminalizing our parents. So the aperture of their vision is much broader. This new, potential bill that may come from the President and some Democrats is offensive to many of the leaders here because they are saying, “Are we are just going to accept whatever comes to us, and not our little brothers and sisters? We are not going to accept legislation on those terms from a white supremacist." The narratives are very sophisticated and the vocabulary is changing. And it's fascinating to hear that, because it's very bold and compassionate at the same time.

Alex: You make a great point, David. I lived with this shame for thirty years. People come and they see my show that I've known for ten, twenty years and they come up after the show, and they give me a big hug and they look me in the eyes and they go, “I had no idea.” And I go, “Exactly, that's the whole point, you aren't supposed to know, because it's something that was shameful and embarrassing.”

Karen: The thing people don’t know is that there is no path to citizenship if you came in here without papers. There is just no path. You have to go back to your country, and apply, and let everything go, and that's a crazy gamble. That's why there are people who have been married to American citizens for decades who are getting deported at this moment. You know “We the People” is an idea—it’s not saying “We the Citizens.” We the people are the people living and working and dying on this land that we call United States of America. And you know, to say that all of us are not a part of this fabric, and do not have a voice, and that there is no way to change the legal recourse, it's very anti-American in my mind. It's a crazy idea that because of some legal thing, millions and millions of people have no way of becoming American citizens. I do not know how that benefits this country at all.

Alex: I do not think that it benefits anyone at all. I've had conversations with friends that are undocumented, and very much like what David was saying, we ourselves are taking it into our own hands and changing the narrative, because we are dealing with circumstances that are outside our control. I think that is the most important thing, because being documented for a couple of years has given clarity to a lot of people like myself. We have to live in the shadows, not because we are bad people, or because we are less than human, or because we did something wrong. We were brought into this country with the understanding and the hope that we were going to be able to do better than our parents were offered in their home countries. I mean, our parents sacrificed their livelihoods. I look at my own personal family tree. My mother came here when she was fifteen years old. She brought me over and I almost died, trying to cross over from Tijuana to San Ysidro. My father immigrated here when he was nineteen years old. He wanted to be a lawyer, but he lived and died as a car painter. His life ended abruptly at the age of thirty-five. My mother wanted to be a police officer, and she went to school even though she was undocumented, she got two degrees, but because she didn't have papers she wasn't able to become a police officer. And by the time she did get papers because she married a serviceman, she was too old. So my parents sacrificed their livelihoods, their hopes, and their dreams, in the hope that their children, myself and my siblings, would be able to benefit from opportunities.

We were really trying to have an intellectual and an emotional discussion all at once. And people were ready for that. I am hoping that if they are not being moved by these stories, then at least they can start listening again.—Karen Zacarías

Karen: How are people responding to your plays?

David: What's interesting is that we premiered this play in the spring of 2016. It was during the primaries. Now we are presenting it over a year later. So much of our play was based on the Dreamers considering breaking with their traditional allies, the local Democrats that they worked for. The conundrum for the Dreamers is, do we abandon them, and do we go grassroots, or do we do the unspeakable and support the most unlikely candidate, which is this wild, fringe, Republican that has decided to support immigration reform? When we presented it the first time at the Dallas Theater Center, with very conservative audiences as well as Latino audiences, we would see people that were very sympathetic to the choices of the Dreamers that were considering getting behind this Republican. Right now there is not much patience for that sort of attitude, which is interesting.

The Dreamers, and a lot of the people in the undocumented community, relate to the problem and the conundrum, and to the frustrations with the Democratic party, but they hesitate at the idea of stepping into the partnership with a politician with such an extreme right agenda. However, there are some undocumented folks here that are Republican.

The first time we presented it, I think that there was a belief that there were moderate positions within our parties. And I think that now the view of the party system is that the parties are so extreme, that creating a bridge is not as realistic as before.

Alex: We have got to understand that policies are based on people's own perceptions of what they want to see in their communities and their societies. I am very liberal on a lot of things, but I am very conservative when it comes to other things. And just picking a political party, being in a two party system...I do not necessarily subscribe to that.

You brought up something very interesting that I want to ask you about, David. How do you get audiences that are not traditionally sympatric to immigration reform, or even against immigration? Because those are the audiences that I'm interested in having to come out and see Wet. It’s easy to get people that are already on board, but to bring a whole new audience—how do you get those kinds of people to come and see something like Deferred Action?

David: The first time we produced it, it was produced with the single LORT theatre in Dallas, which is a predominantly white institution, with a predominantly white subscriber base and ticket buying audience. Just by the mere fact of the season subscribers having tickets or people knowing the theatre, they would buy tickets. We had some incredible audiences. There was one audience in which the Tea Party Republican was insulting the Dreamers and we audience members cheered for his statements. There was one night where one of the undocumented protesters was maced and someone cheered. And there was a verbal confrontation at intermission about that. But through engaging the audience during discussions afterwards, I think many audience members were educated and became impassioned about the movement.

Karen: I had a similar experience at the Denver Center, who did Just Like Us because it was a local story. It was one of the most diverse audiences they had ever had, but it also created this great dialogue. We had the same thing—we had people yell from the audience at the characters, but more than that we saw the amazing power of theatre to humanize, to show the story from the point of view of these young girls. We were really trying to have an intellectual and an emotional discussion all at once. And people were ready for that. I am hoping that if they are not being moved by these stories, then at least they can start listening again. We just need find some kind of compromise, which is never going to be perfect, but everything is dying in the water again and again and again, and meanwhile our Dreamers are becoming thirty, forty-

Alex: We are getting old!

Karen: Yeah! You want to be sure that if and when you decide to have kids, you can be here to raise them.

Alex: Yeah. I do have a fifteen-year-old daughter who lives with me—I am a full time single dad—and we do fear that one day I am not going to pick her up from school. Or that they are going to come kick down our door and take me away, and then she is never going to see me. This is cruel and unusual punishment to US citizens because my daughter has no fault in this whole thing, you know? She is a good kid, she goes to a great school, she has these big dreams and hopes. I am raising someone that wants to be a productive member of society, and is a productive member within her own community, and for her to have to feel that fear, going, “But Dad, do I have to wait until I am twenty-one so that I can claim you? So that you can get your papers through me?” Why should a fifteen-year-old be having that conversation with her father? She says, “I can't wait to grow up so that I can petition for you to stay in the country.”

This leads me to my next point: we are not desperate, but we are getting so frustrated because we are already very severely limited, and now they are even more limited. People were trying to use the advance parole clause to be able to go to their home countries to visit ailing grandparents or parents—people they have not seen in so many years. And with the elimination of the DACA program, they also eliminated the advanced parole option, so kids that have DACA that want to visit their ailing parents or that want to travel abroad with school type of field trip, or even conduct business in other parts of the world because their industry requires them to do so, can no longer do it.

Karen: I find it just phenomenally depressing that something that was said and promised to so many people is now being chipped away.

Alex: It's even to the point where I am afraid to travel again. For four years I was able to travel within the country, and now I do not even want to go to Orange County, which is like fifty miles away from Los Angeles, and every time I drive down there I have this concern of “Oh my God, I hope I do not get pulled over.” But I have a driver's license, I have insurance, all my paperwork is current, and I hadn't felt that way in years.

Karen: Yeah. We had two young men who had gotten soccer scholarships here from El Salvador, and they got picked up and sent back home before the schools could even say anything. It was so incredible. And that just dashed all of their dreams, and the universities were like, “But wait, we want these kids, they are good students, they are great soccer players, good people.” I don’t mean to talk about well-behaved as being the center of it—

Alex: Well, it creates this incredible amount of pressure on undocumented individuals, or Dreamers, because we are supposed to be perfect, right? We are not allowed to make mistakes. I have a very good friend from college who, when he was younger—you know everybody does dumb things when they are kids—got caught with a gram of marijuana, before it was legal. And that gram of marijuana cost him two felonies because they were claiming he had the intent to sell. And because he was undocumented, he went ahead and he said, “Fine, I just don't want to go to jail, I do not want to get deported.” But those two felonies prevented him from initially applying for DACA.

And so this is a hard-working young man who takes care of his ailing mother and works three jobs and goes to school, he was getting ready to transfer to the University, but because he had the two felonies he did not qualify for anything. It wasn't until marijuana was legalized here in California that he was able to overturn those two convictions and get them off his record. He applied for DACA, and now that he does have it, he feels a sense of helplessness because he is not going to be able to renew his DACA because it does not expire until almost immediately after the program ends in March. So he only has a very limited amount of time to figure out what he is going to do if our Congress doesn't pass legislation that is going to help us stay here, which is our only home.

Karen: Right. So much of it is just screaming headlines, and I think that's why these pieces of theatre and these books and the idea of these human stories are so important—people need to be able to understand it not through just reading legislation but from the point of view of someone actually living it. Theatre is a way to make people understand everything, from healthcare to immigration to a lot of things that are under siege right now—what the human cost is of ignoring it or repealing it.

Alex: I had a question for you, David. There are a lot of pockets in Texas that are very staunchly anti-immigrant. Do you guys ever receive any kind of hate mail, or have you had anyone that stands up and goes, “This is a farce” and they walk out? Any negative type of reactions to the production that you have been putting up?

David: We have people that walk out of the productions, and we have people that post links to ICE on our Facebook ads. But nothing that really fazes anyone in our community. I think that our undocumented community here, and especially the leaders that I am in contact with, are extraordinarily brave and bold, and so I don't see fear in them. On the day of the Jeff Sessions’ announcement I saw more conviction than before, and I saw more conviction towards the larger group of undocumented immigrants, and conviction to fight for everyone. The community that I am in contact with is a community of fighters, so I think we know the state we are living in, and the anti-immigrant sentiments that are around us, but the communities are strong.

Alex: I am sure that the community feels the support that you and your theatre company provide, and I want to personally thank you for putting these stories out there, and Karen, I want to thank you as well for helping us find a voice. I wouldn't be able to do the show that I am doing if I didn't feel the love and support that I got from my theatre company and my good friend and producer Lizzy Ross. When I first started developing Wet, I had just gotten back from Guatemala. We almost didn't do the production because at the time I was waiting for my work permit to be renewed. We wanted to do the production at the end of April of this year, but we couldn't because we didn't know if I was going to have legal documents that would allow me to legally work in the country. Thank God they came in at the end of March, which is two weeks before my old permit expired, and then we moved forward with putting the production up.

I was in the third week of the run when Jeff Sessions made the announcement of the resending of DACA. I broke down, I felt like the life was being sucked out of me. And Liz said, “Look, you are loved, you are supported, people need to hear this story because it is important to see that there is a human face behind the politics, and the policies.”

I guess what I am trying to say is thank you for being advocates, and thank you for being allies because people like myself have lived our entire lives feeling alone and abandoned and unsupported and suddenly there is this huge outpouring of support, there is this huge outpouring of understanding.

David: Wow, thank you for sharing that.

Karen: Absolutely. I second that.

David: Wow. It's been very humbling for me to be involved in this project, to be a writer and a co-writer and a director and producer, and I want to do more. I am heartbroken by the politics of the situation and the suffering that it causes. But even though I have co-written this play, I know I can never truly understand what an undocumented immigrant goes through, especially one that has known only this country. So I am just humbled by the extraordinary capacity of the undocumented youth and the undocumented population in this country, and continue to maintain this pursuit of claiming their right to be here, which I fully support. I am daily humbled by the privilege of being able to tell this story.

Alex: Thank you so much, guys.

Karen: I am heartened by the fact that universities that have not been aware of the DACA problem are now aware and fighting and demonstrating about it, I am heartened that there are readings happening, that Deferred Action is going around, that your play is up and Just Like Us, I only hope it translates into more sustainable action that puts pressure on our elected officials to really change it.

***

¿Qué sucede cuando las historias que cuentas de pronto se convierten políticamente relevantes a las masas? Cuando el Presidente Donald Trump anunció que anularía el programa Acción Diferida para los Llegados en la Infancia (DACA) en marzo del 2018, las personas indocumentadas fueron el foco de la nación. Mientras las autoridades políticas expusieron sus reacciones ante el anuncio, las personas sin documentos quedaron rutinariamente fuera de la conversación, o fueron estereotipados como inmigrantes “buenos” o “malos.” El actor y escritor Alex Alpharaoh (Los Ángeles, CA) quien nació en Guatemala y está indocumentado, el escritor y director David Lozano (Dallas, TX) quien nació en los Estados Unidos y es un ciudadano estadounidense, y la dramaturga Karen Zacarías (Washington, DC) quien nació en México y solo apenas fue entregada su ciudadanía de EEUU, conversan sobre su trabajo que se centra en las historias de personas indocumentadas, los activistas quienes luchan con y por ellos, la complicada naturaleza de está legislación defectuosa, y cómo se siente que de repente sus trabajos sean más relevantes que nunca.

Alex: Mi presentación como solista Wet: A DACAmented Journey narra mi vida, mi trayecto personal como un estadounidense indocumentado que ha estado en los Estados Unidos desde que tenía tres meses. Soy uno de los beneficiarios más antiguos de DACA: apenas cumplí con el plazo por unos meses. Narra la historia de lo que tuve que hacer para tratar de ajustar mi estado en el país y obtener la residencia legal después de que la administración cuadragésima quinta asumió el poder y comenzó a implementar sistemas que intentarían deportar a más de 11 millones de personas indocumentadas en el país, incluyendo a los beneficiarios de DACA que ahora están en riesgo porque el programa DACA ha sido anulado.

Karen: Tu obra tiene que ir a todos lados, eso por seguro.

Alex: Pues, gracias. Acabamos de cerrar las primeras funciones en Ensemble Studio Theater Los Ángeles, la estaremos regresando por un tiempo limitado en octubre, y luego se va al Festival Internacional Encuentro de las Américas en noviembre.

Karen: Siento mucho que tenga que ser tan relevante, pero no se me ocurre una declaración más poderosa. Quiero que todos los congresistas vean tu obra.

Alex: Gracias, sí. Siento un conflicto al respecto porque estoy recibiendo un gran reconocimiento—la gente se está conectando realmente con la historia y está educando a personas que tal vez no saben cómo es ser un estadounidense indocumentado—pero al mismo tiempo la situación es injusta. El cien por ciento de los beneficiarios de DACA no tienen antecedentes penales, y la mayoría de ellos son ciudadanos ejemplares, y que sean categorizados con traficantes de drogas, ladrones y asesinos y personas que vienen aquí a robar trabajos e identidades es la retórica que estoy tratando de ayudar a cambiar. Estoy seguro de que la pieza de David, Deferred Action, y tu trabajo también están sacando este tema a la luz.

Karen: Absolutamente. Yo tengo una historia de inmigración diferente. De por sí me convertí en una ciudadana estadounidense el viernes, después de un largo trayecto. Fui una de las primeras personas en ver el video de “Bienvenidos, nuevos ciudadanos” de Trump, y dejame decirte, no tenía nada de bienvenida. Este es un tiempo difícil para ser inmigrante.

Yo vine acá de niña con una Visa a través del trabajo de mi padre, y luego el gobierno estadounidense en algún punto dijo, “Queremos que tu padre y tu madre se queden, pero a ti se te acabó el tiempo. Sabemos que te has criado aquí, todos tus amigos están aquí, tu familia está aquí, pero necesitas regresarte tu sola.” Y yo me quede como que, “¿A quien, a que, a donde? Aquí es donde yo crecí. Los niños se van a donde sus padres vayan.”

Tuve la afortunada oportunidad de adaptar el libro llamado Just Like Us escrito por Helen Thorpe para el Denver Center. Narra la vida de cuatro niñas nacidas todas en México, pero dos de ellas tienen documentos y las otras dos no. Todas son estudiantes de buenas notas y líderes en su colegio, pero trata de cómo las niñas que están documentadas tienen oportunidades que las otras dos indocumentadas no tienen. La obra hace una crónica de estas cuatro niñas sobre el contexto creciente anti-inmigratorio por los eventos del 11 de septiembre y el homicidio de un policía en Denver por un joven indocumentado. La obra toca todo tipo de matices e intenta disipar los mitos que mencionaste, Alex - los niños de DACA son buenos alumnos, están dedicados a ser parte de la comunidad, no tienen antecedentes penales, tienen tanto que aportar a la ciudadanía americana. Parece ser de corta visión, económicamente estúpido, y moralmente incorrecto rescindir esta promesa que le hicimos a estos jóvenes que verdaderamente son americanos de todas las maneras posibles excepto en papel.

David: He estado en contacto con Soñadores en Dallas desde que regrese a Cara Mia Theatre en el 2009, y nuestra primera obra que producimos fue una obra política sobre unos adolescentes en Crystal City, Texas. Primero, lideraron una marcha que duró varios meses en protesta a los castigos por hablar español, y en favor a transformar los currículos a uno que refleje la experiencia mexicana y mexicana-americana, cuya era la mayoría de la población de Crystal City. Y luego los estudiantes fueron inspirados a motivar a sus padres a postularse para los cargos públicos, y los estudiantes les hicieron campañas a sus padres y los Mexicano-americanos en el pueblo terminaron quedando en el poder del distrito escolar y el consejo municipal. A los Soñadores les ha atraído mucho esta historia, y se han convertido en seguidores de Cara Mía. Me hice amigo cercano del fundador de North Texas Dream Team, Ramiro Luna. Me impactó la posición difícil en la que él estaba, como alguien que trabajaba con políticos y autoridades electas, pero que siempre los estaba retando. Cuando el Dream Act no pasó en el 2010, el estaba devastado. El fue un activista audaz y frecuentemente creaba teatro político y teatro guerrilla - presentaciones que atraían la atención de la prensa, y atención a la hipocresía de los políticos. Esta tensión entre trabajar con los políticos demócratas mientras también retaba a otros de maneras muy audaces, fue lo que más me impactó.

Esto se convirtió en mi inspiración para Deferred Action, y de muchas maneras el título de la obra se refiere a la acción diferida de nuestros oficiales electos quienes no han aprobado un cambio migratorio. Los personajes son Ramiro y su colaborador cercano Marco Malagón y otro amigo nuestro. Cuando Lee Trull y yo decidimos trabajar juntos en esta obra, que fue desarrollada en el Dallas Theater Center como co-producción con Cara Mia, entrevistamos a tres de ellos durante dos o tres años, y desarrollamos una historia inspirada en la situación en la que viven.

La obra se trata de dos políticos de Texas quienes tienen la posibilidad de ser el nominado candidato Presidencial. Una es una demócrata latina y el otro el un Republicano del movimiento Tea Party. Durante el transcurso de la obra de teatro, el protagonista expresa su frustración con la demócrata latina quien no es muy vocal ante la reforma migratoria. El candidato Tea Party comienza con comentarios belicosos sobre los inmigrantes, pero termina teniendo un sueño que le hace cambiar de opinión de la noche a la mañana, y decide apuntar una legislación de reforma migratoria total y se lanza a la presidencia. Entonces los Soñadores no saben a quien apoyar.

Alex: Es muy interesante que estés tocando todos estos diferentes temas y contextos delicados - eso es muy importante que las personas vean. Una cosa que pareciera que siempre surge en conversaciones es el término “Soñador.” Como un individuo indocumentado, es dificil para mi asociarme con el término Soñador y creo que eso es algo que se está dispersando entre la comunidad indocumentada, sencillamente porque es una legislación que ha fallado. Es una legislación que ha decepcionado a la comunidad por más de una década ya. Si nada pasa en los próximos años, habrán pasado veinte años intentando aprobar una ley que ha fallado por una razón u otra. Alguien una vez dijo, “¡Eres un Soñador, entonces tienes esperanza!” Y le dije, “No, soy un realista.” Tener sueños no tiene nada que ver.

Karen: Conozco a muchas personas que están indocumentadas, muchos de mis estudiantes no lo están, pero no son Soñadores oficialmente. Hay todo otro grupo de gente joven que ni es parte de ese programa en específico al que te tienes que inscribir. El término Soñador evoca una cierta esperanza y calidez que es lo opuesto a la realidad de lo que está pasando.

Alex: Me duele que por tantos años hemos dejado nuestra esperanza en las manos de estos representantes electos.

David: Esta iteración de nuestra producción es en verdad sobre cómo la comunidad de jóvenes que están cambiando la narrativa, y cambiando el vocabulario. Uno de los miembros de nuestro elenco me respondió sobre qué estamos corrigiendo de las narrativas que fueron creadas desde antes, y fue “Somos estudiantes estupendos, nos portamos bien, somos educados y profesionales.” Lo que eso hizo fue alienar a aquellos que capaz no son buenos alumnos, que capaz no se portan bien. Pero aún, la idea de ser traídos por nuestros padres sin nuestro permiso criminaliza nuestros padres. Entonces la visión que tienen va mucho más allá. Esta nueva legislación potencial que puede venir del Presidente y algunos Demócratas es ofensivo a muchos de nuestros líderes aquí porque están diciendo, “¿Vamos a aceptar cualquier cosa que nos llegue a nosotros, y no a nuestros hermanos y hermanas menores?” No vamos a aceptar la legislación en esos términos de supremacía blanca. Las narrativas son muy sofisticadas y el vocabulario está cambiando. Y es fascinante escuchar eso, porque es muy audaz y compasivo al mismo tiempo.

Alex: Haces un buen punto, David. Yo viví con esta vergüenza por treinta años. La gente viene y ve mi obra y los conozco desde hace diez, veinte años y aparecen después de la función, y me dan un gran abrazo y me miran a los ojos y me dicen: "No tenía ni idea". Y les digo: "Exactamente, ese es el punto, se supone que no debes saberlo, porque es algo infamante y vergonzoso."

Karen: Lo que la gente no sabe es que no hay un camino hacia la ciudadanía si vienes aquí sin papeles. Simplemente no hay camino. Tienes que volver a tu país, aplicar y dejar todo ir, y eso es un riesgo loco. Es por eso que hay personas que se han casado con ciudadanos estadounidenses quienes están siendo deportados en este momento. Saben que "We the People (Nosotros, la Gente)" es una idea - no quiere decir "We the Citizens (Nosotros, los Ciudadanos)". Nosotros, la gente, vivimos, trabajamos y morimos en esta tierra que llamamos los Estados Unidos de América. Y sabes, decir que todos nosotros no somos parte de este tejido, y no tenemos voz, y que no hay forma de cambiar el recurso legal, es muy antiamericano en mi mente. Es una idea loca que, debido a algo legal, millones de millones de personas no tienen forma de convertirse en ciudadanos estadounidenses. No sé cómo eso beneficia a este país en absoluto.

Alex: No creo que beneficie a nadie en absoluto. He tenido conversaciones con amigos que no están documentados, y muy parecido a lo que David estaba diciendo, nosotros mismos lo estamos tomando en nuestras propias manos y cambiando la narrativa, porque estamos lidiando con circunstancias que están fuera de nuestro control. Creo que eso es lo más importante, porque el estar documentado durante un par de años le ha dado claridad a mucha gente como yo. Tenemos que vivir en las sombras, no porque seamos malas personas, o porque somos menos que humanos, o porque hicimos algo malo. Fuimos traídos a este país con el entendimiento y la esperanza de que íbamos a ser capaces de hacerlo mejor de lo que se les ofrecían a nuestros padres en sus países de origen. Quiero decir, nuestros padres sacrificaron sus modos de vida. Miro mi propio árbol familiar. Mi madre vino aquí cuando tenía quince años. Ella me trajo y casi me muero, tratando de cruzar de Tijuana a San Ysidro. Mi padre emigró aquí cuando tenía diecinueve años. Quería ser abogado, pero vivió y murió como pintor de automóviles. Su vida terminó abruptamente a la edad de treinta y cinco años. Mi madre quería ser policía, y ella fue a la escuela a pesar de que no tenía documentos, obtuvo dos títulos, pero como no tenía documentos, no pudo convertirse en agente de policía. Y para cuando consiguió los papeles porque se había casado con un militar, ya era demasiado mayor. Entonces mis padres sacrificaron sus sustentos de vida, sus esperanzas y sus sueños, con la esperanza de que sus hijos, yo y mis hermanos, pudiéramos aprovechar las oportunidades.

Karen: ¿Cómo están respondiendo las personas a tus obras?

David: Lo interesante es que estrenamos esta obra en la primavera del 2016. Fue durante las primarias. Ahora la presentamos más de un año después. Gran parte de nuestra obra se basa en que los Soñadores consideran romper con sus aliados tradicionales, los demócratas locales para quienes les trabajaban. El problema para los Soñadores es, ¿los abandonamos, y seguimos como un movimiento de base, o hacemos lo indescriptible y apoyamos al candidato más improbable, que es este republicano salvaje y marginal que ha decidido apoyar la reforma migratoria? Cuando lo presentamos por primera vez en el Dallas Theatre Center, con audiencias muy conservadoras y audiencias latinas, veíamos a personas que simpatizaban con las decisiones de los Soñadores que estaban considerando respaldar a este republicano. En este momento no hay mucha paciencia para ese tipo de actitud, lo cual es interesante.

Los Soñadores, y mucha gente de la comunidad indocumentada, se sienten identificados con el problema y la complicación, y con las frustraciones con el partido Demócrata, pero dudan en la idea de entrar en asociación con un político con un agenda tan extremamente derecha. Sin embargo, hay algunas personas indocumentadas aquí que son republicanas.

La primera vez que lo presentamos, creo que existía la creencia de que habían posiciones moderadas dentro de nuestros partidos. Y creo que ahora la visión del sistema de partidos es que los partidos son tan extremistas, que crear un puente entre ellos no es tan realista como lo era antes.

Alex: Tenemos que entender que las políticas se basan en las percepciones de las personas sobre lo que ellos quieren ver en sus comunidades y sus sociedades. Soy muy liberal en muchas cosas, pero soy muy conservador cuando se trata de otras. Y simplemente escoger un partido político, estar en un sistema de dos partidos ... No me suscribo necesariamente a eso.

Dijiste algo muy interesante de lo que quiero preguntarte, David. ¿Cómo se obtiene un público que tradicionalmente no simpatiza con la reforma migratoria o incluso con la inmigración? Porque esos son los públicos que me interesan tener salir a ver Wet. Es fácil conseguir gente que ya apoya la idea, pero para atraer a una audiencia completamente nueva: ¿cómo logras que ese tipo de persona venga a ver algo como Deferred Action?

David: La primera vez que lo produjimos fue producido con el único teatro LORT en Dallas, que es una institución predominantemente blanca, con una base de suscriptores y compradores de entrada predominantemente blanca. Solo por el mero hecho de que los suscriptores de la temporada tengan entradas o que la gente conozca el teatro, compraban los boletos. Tuvimos algunas audiencias increíbles. Hubo una audiencia en la que Tea Party Republican insultaba a los Soñadores y los miembros del público aplaudían sus declaraciones. Hubo una noche en la que mataron a uno de los manifestantes indocumentados y alguien aplaudió. Y hubo una confrontación verbal en el intermedio sobre eso. Pero a través de la participación de la audiencia durante las discusiones después, creo que muchos miembros de la audiencia fueron educados y se apasionaron por el movimiento.

Karen: Tuve una experiencia similar en el Denver Center, quienes hicieron Just Like Us porque era una historia local. Fue una de las audiencias más diversas que han tenido, pero también creó este gran diálogo. Tuvimos la misma cosa: teníamos gente que les gritaba a los personajes, pero más que eso, vimos el increíble poder del teatro para humanizar, para mostrar la historia desde el punto de vista de estas jóvenes. Realmente estábamos tratando de tener una discusión intelectual y emocional al mismo tiempo. Y la gente estaba lista para eso. Espero que si estas historias no les conmueven, al menos puedan comenzar a escuchar de nuevo. Solo necesitamos encontrar algún tipo de compromiso, que nunca va a ser perfecto, pero todo está muriendo en el agua una y otra y otra vez, y mientras tanto nuestros Soñadores están cunpliendo treinta, cuarenta ...

Alex: ¡Nos estamos poniendo viejos!

Karen: ¡Si! Uno quiere estar seguro de que si y cuando uno decida tener hijos, uno pueda estar aquí para criarlos.

Alex: Sí. Tengo una hija de quince años que vive conmigo, soy un padre soltero de jornada completa, y tememos que algún día no la vaya a buscar a la escuela. O que van a venir a patear nuestra puerta y llevarme lejos, y entonces ella nunca me va a ver. Este es un castigo cruel e inusual para los ciudadanos estadounidenses porque mi hija no tiene ninguna culpa en todo esto, ¿sabes? Ella es una buena niña, va a una gran escuela, tiene grandes sueños y esperanzas. Estoy criando a alguien que quiere ser una miembra productiva de la sociedad, y es una miembra productiva dentro de su propia comunidad, y para que ella tenga que sentir ese miedo, diciendo: "Pero papá, tengo que esperar hasta que tenga veintiún años para poder reclamarte? ¿Para que puedas obtener tus papeles a través de mí? "¿Por qué debería una niña de quince años tener esa conversación con su padre? Ella dice: "No puedo esperar a crecer para poder pedir que te quedes en el país."

Esto me lleva a mi siguiente punto: no estamos desesperados, pero nos estamos frustrando porque ya estamos muy limitados, y ahora somos aún más limitados. La gente intentaba utilizar la cláusula anticipada de libertad condicional para poder ir a sus países de origen a visitar a sus abuelos o padres enfermos, personas a las que no habían visto en tantos años. Y con la eliminación del programa DACA, también eliminaron la opción de libertad condicional avanzada, para que los niños que tienen DACA que desearan visitar a sus padres enfermos o que desearan viajar al exterior con un tipo de viaje escolar o incluso realizar negocios en otras partes del mundo porque su industria requiere que lo hagan, ya no pueden hacerlo.

Karen: Me parece increíblemente deprimente que algo que se dijo y se prometió a tanta gente ahora está siendo eliminado.

Alex: Es incluso hasta el punto en que tengo miedo de salir de viaje otra vez. Durante cuatro años pude viajar dentro del país, y ahora ni siquiera quiero ir a Orange County, que está a ochenta millas de Los Ángeles, y cada vez que conduzco allí tengo esta preocupación de "Ay Dios mío, espero no ser detenido." Pero tengo una licencia de conducir, tengo seguro, todos mis documentos están actualizado, y no me había sentido así en años.

Karen: Sí. Tuvimos a dos hombres jóvenes que habían obtenido becas de fútbol aquí desde El Salvador, y los recogieron y los mandaron de regreso antes de que las escuelas pudieran decir algo. Fue tan increíble. Y eso acabó arruinando todos sus sueños, y las universidades decían: "Pero esperen, queremos a estos niños, son buenos estudiantes, son grandes jugadores de fútbol, buenas personas". No me refiero a hablar de buen comportamiento como el centro de esto -

Alex: Bueno, si se crea esta cantidad increíble de presión sobre las personas indocumentadas, o Soñadores, porque se supone que somos perfectos, ¿verdad? No podemos cometer errores. Tengo un muy buen amigo de la universidad que, cuando era más joven - sabes que todo el mundo hace tonterías cuando es niño - fue atrapado con un gramo de marihuana, antes de que fuera legal. Y ese gramo de marihuana le costó dos delitos porque decían que tenía la intención de vender. Y debido a que era indocumentado, se adelantó y dijo: "Bien, simplemente no quiero ir a la cárcel, no quiero que me deporten." Pero esos dos delitos no le permitieron solicitar inicialmente DACA.

Y entonces este es un joven trabajador que cuida a su madre enferma y trabaja en tres empleos y va a la escuela, se estaba preparando para transferirse a la Universidad, pero como tenía los dos delitos no calificaba para nada. No fue hasta que la marihuana se legalizó aquí en California que pudo anular esas dos convicciones y sacarlas de su registro. Solicitó DACA, y ahora que lo tiene, siente una sensación de impotencia porque no va a poder renovar su DACA porque no se vence hasta casi inmediatamente después de que el programa finalice en marzo. Así que solo tiene un tiempo muy limitado para descubrir qué hará si nuestro Congreso no aprueba una ley que nos ayude a permanecer aquí, que es nuestro único hogar.

Karen: Correcto. Gran parte de esto solo está gritando titulares, y creo que es por eso que estas piezas de teatro y estos libros y la idea de estas historias humanas son tan importantes, las personas necesitan poder entenderlo no solo leyendo leyes, sino desde el punto de vista de alguien que realmente lo vive. El teatro es una manera de hacer que las personas entiendan todo, desde el cuidado de salud a la inmigración a muchas cosas que están bajo asedio en este momento: cuál es el costo humano de ignorarlo o revocarlo.

Alex: Tengo una pregunta para ti, David. Hay muchas partes en Texas que son incondicionalmente antiinmigrantes. ¿Alguna vez han recibido algún tipo de correo insultante o alguien que se haya levantado y dicho: "Esto es una farsa" y se van? ¿Algún tipo de reacciones negativas a la producción que has estado presentando?

David: Tenemos personas que abandonan las producciones, y tenemos personas que publican enlaces a ICE en nuestros anuncios de Facebook. Pero nada que realmente deslumbre a nadie en nuestra comunidad. Creo que nuestra comunidad indocumentada aquí, y especialmente los líderes con los que estoy en contacto, son extraordinariamente valientes y audaces, por lo que no veo miedo en ellos. El día del anuncio de Jeff Sessions, vi más convicción que antes, y vi más convicción hacia el gran grupo de inmigrantes indocumentados y convicción de luchar por todos. La comunidad con la que estoy en contacto es una comunidad de luchadores, por lo que creo que sabemos el estado en el que vivimos y los sentimientos antiinmigrantes que nos rodean, pero las comunidades son fuertes.

Alex: Estoy seguro de que la comunidad siente el apoyo que usted y su compañía teatral brindan, y quiero agradecerle personalmente por exponer estas historias ahí, y Karen, quiero agradecerle también por ayudarnos a encontrar una voz. No podría hacer la función que estoy haciendo si no sintiera el amor y el apoyo que recibí de mi compañía de teatro y mi buena amiga y productora Lizzy Ross. Cuando comencé a desarrollar Wet, acababa de regresar de Guatemala. Casi no hicimos la producción porque en ese momento estaba esperando la renovación de mi permiso de trabajo. Queríamos hacer la producción a finales de abril de este año, pero no pudimos porque no sabíamos si iba a tener documentos legales que me permitieran trabajar legalmente en el país. Gracias a Dios que llegaron a finales de marzo, dos semanas antes de que expirara mi antiguo permiso, y luego seguimos adelante con la producción.

Estaba en la tercera semana de la presentación cuando Jeff Sessions hizo el anuncio de la anulación de DACA. Me derrumbé, sentí que la vida estaba siendo aspirada fuera de mí. Y Liz dijo: "Mire, eres amado, tienes apoyo, la gente necesita escuchar esta historia porque es importante ver que hay un rostro humano detrás de la política y las legislaciones."

Supongo que lo que estoy tratando de decir es gracias por ser defensores, y gracias por ser aliados porque personas como yo hemos vivido toda nuestra vida sintiéndonos solos y abandonados y sin apoyo, y de repente hay una gran cantidad de apoyo, hay esta enorme efusión de entendimiento.

David: Wow, gracias por compartir eso.

Karen: Absolutamente. Estoy de acuerdo con lo que has dicho.

David: Wow. Para mi ha sido muy gratificante participar en este proyecto, ser escritor, coautor, director y productor, y quiero hacer más. Estoy desconsolado por la política de la situación y el sufrimiento que causa. Pero a pesar de que he coescrito esta obra, sé que nunca voy a poder entender realmente lo que vive un inmigrante indocumentado, especialmente uno que solo ha conocido este país. Así que me siento honrado por la extraordinaria capacidad de la juventud indocumentada y la población indocumentada en este país, y sigo manteniendo esta búsqueda de reclamar su derecho a estar aquí, lo cual apoyo totalmente. Cada día me siento honrado por el privilegio de poder contar esta historia.

Alex: Muchísimas gracias, chicos.

Karen: Me siento alentado por el hecho de que las universidades que no conocen el problema de DACA ahora están conscientes y peleando y demostrandose al respecto, me alienta que hayan lecturas sucediendo, que Deferred Action esté de gira, que su obra y Just Like Us están en función, solo espero que se traduzca a una acción más sostenible que presione a nuestros funcionarios electos para que realmente lo modifiquen.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here

I also keep re-reading. This is why i got into theatre--to have these important conversations and shine light on important work being done. Thank you so, so much.

Wow! This is such a powerful and necessary conversation---I've read it 3 times since it was published yesterday!

I've had the pleasure of seeing "Deferring Action" several times and can speak to the power of the play to spark conversations and challenge audiences. I'm looking forward to seeing "Wet" at Encuentro and "Just Like Us" in November at a reading in Houston.

Thanks to Karen, David, and Alex for all of the work that you do!