Being Real

A. Rey Pamatmat and the New American Identity

This is how playwright A. Rey Pamatmat responded when I asked him a while back (for another article) what unifying concept lay at the heart of his body of work:

All of my plays usually start with confusion: something in the world doesn't make sense to me, or two very different things seem related but I don't know why or how. When that confusion crystallizes into a question, I start writing—writing for me is a search for answers and understanding. Perhaps because of that my plays tend to be about self-actualization both for individuals, and for groups—people or communities using their own power to change or determine their fate.

Two of Pamatmat’s plays, after all the terrible things I do and Edith Can Shoot Things and Hit Them, are being co-produced by the Huntington Theatre Company and Company One Theatre, respectively. It’s the first time his work has been performed on Boston stages.

In the opening scene of after all the terrible things I do, a flustered but earnest Daniel (Zachary Booth) sits down for a job interview at the bookstore he visited frequently as a child. “I need to make a connection to the place where I was young,” he says. Later, he admits, “I’m trying to be more real.”

His admission made me think about the place where I was young. My history; my “lived feelings,” in his words.

I was born and raised in Delaware, in a suburb thirty minutes south of Philadelphia. I attended Catholic school from first through twelfth grade. I rode horses for several years, and, in the summers, I went to day camp. In high school, I played field hockey, lacrosse, and ran cross-country.

A pretty ordinary childhood for a privileged white-passing kid.

On the weekends, my family would travel to Philadelphia for dim sum and hit up the Chinatown bakeries for bibingka and siopao. I have many memories of sitting in the kitchen with my grandmother as she rolled pyramids of pork lumpia and wrapped bundles of tupig in banana leaves. The television was always turned up a little too high, voices overlapping in rapid-fire Tagalog. When my grandfather died, we participated in pasiyam and prayed the rosary every night for nine days.

If the second set of experiences didn’t resonate with you, then it’s probably because you’re not of Filipino heritage. But does it call into question the authenticity of my American upbringing? Furthermore, what is the identity of the American family in our supposedly modern age? What is “real?”

In another HowlRound article from 2013, Pamatmat remarks,

In the lobby for a production of my play Edith Can Shoot Things and Hit Them I overheard a woman say, “This play would get done everywhere if the main characters weren’t Asian.” Discussing the same play, a young future theatre professional asked, “Why are Kenny and Edith Filipino?” To which I replied, “Why are you white?”

Later in the piece, he shares,

I’m often confronted by “compliments” that my plays aren’t “just” gay plays or “just” Asian-American plays. Then, on the flip side, I’m criticized that they aren’t gay or Asian “enough.” The implication is that my life experience is a limit rather than a gift, when the real limit is what others’ ideas of what gay or Asian-American plays can be.

I’ve never had to qualify my American-ness on account of my being white. As a mixed-race individual, my Asian background added a dimension of duality to my experience that simply existed, unremarked upon, unless in specific contexts. But for visibly brown people, it just doesn’t work that way.

In the theatre world, at least, real American lives onstage remain solidly signified with whiteness.

In the theatre world, at least, real American lives onstage remain solidly signified with whiteness.

In a review of after all the terrible things I do, one writer states,

Daniel speaks with the polished craft and complete sentences of a writer—and based on the recitations built into the script, the Huntington could conceivably host an evening devoted to Booth performing the work of O’Hara. But Linda [a Filipina] sounds like the creation of a playwright who’s not yet mastered the task of capturing the cadences of everyday speech.

Another says of Edith:

Like Pamatmat himself, Kenny and Edith (who’s mostly called Ed or Eddie, as if she were a boy) are Filipino-American. They make the occasional reference to their favorite Filipino dishes, but I wish more of their culture were on display, and it seems odd that they have no racial problems at school.

These reviewers, perhaps unconsciously, are speaking to the larger problem at hand: a brown body onstage is unable to be anything more than just that. He, she, or they will always be reduced to that common denominator, the color of their skin dictating the way their narrative is meant to go. Perhaps Linda sounds strange because English is not her first language. Perhaps there are not constant references to Kenny and Edith’s heritage because it is not relevant to their story of navigating first love and parental abuse. Perhaps Edith is referred to as “Ed” simply because that is her name.

***

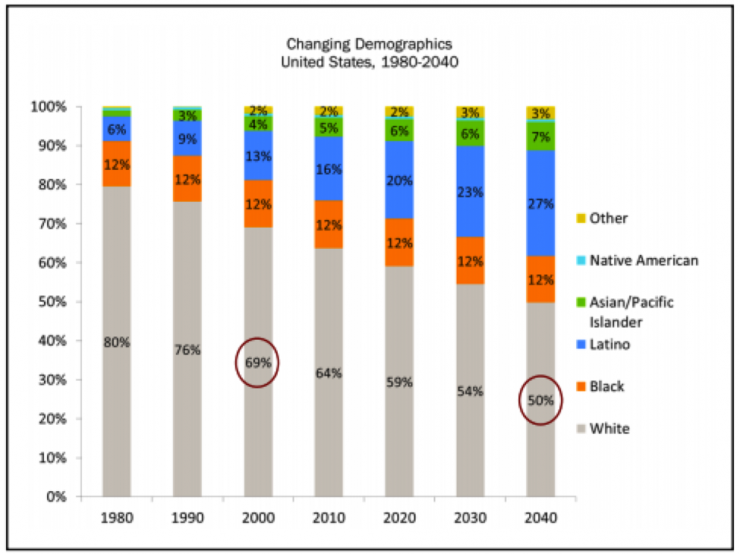

Last month, the Barr Foundation and Boston Creates (the city’s new cultural planning initiative) hosted a talk on the role of the arts in contributing to Boston’s evolving social identity with sociologist and USC professor Dr. Manuel Pastor. At the seminar, he introduced the concept of the Next America: a term that encapsulated the reality that the rising number of people of color in America doesn’t find its root cause in immigration, as many still wrongly assume, but in young people being born and raised here. By 2040, Pastor’s research demonstrated, the word “minority” will hardly be an accurate description anymore.

(The following graphs can be found at the bottom of this article, detailing Professor Pastor’s presentation.)

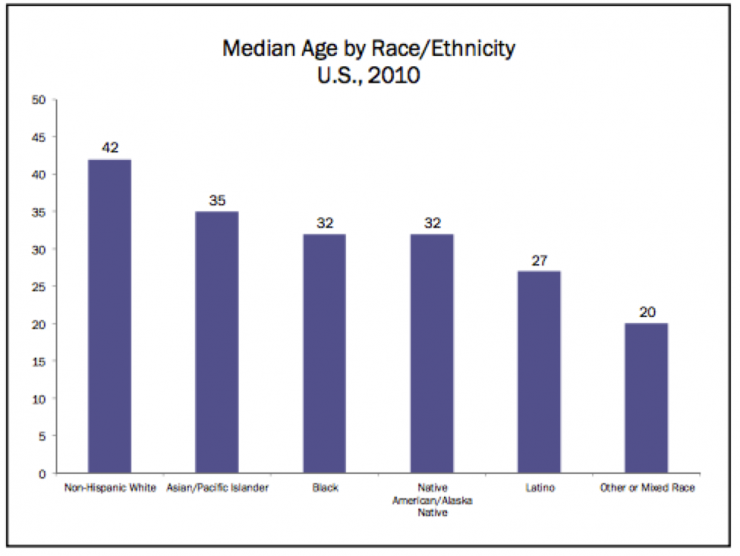

Furthermore, the majority of non-white citizens in America are young—between twenty and thirty-five, in fact. There exists a palpable gulf in the median age of white people and people of color of varying ethnic backgrounds.

What does this mean for the arts? Well, the arts, Pastor argued, are fundamentally about self-expression, community building, and liberation. So then why are we putting constraints on who can express these experiences, and how they should do so?

The arts provide a place where younger folk can find validation of experience; sometimes, it’s the only place. It is meant to be a sanctuary. It is meant to signify freedom. Instead, those very people who need it most are being sent an abundantly clear message: they are, and always will be, “other.”

***

Before the Pamatmat plays premiered, I wrote a preview of the event. In the weeks since, and in the wake of the events that have unfolded, I’ve been going back again and again to something Shawn LaCount, Company One’s artistic director, said in our interview. The whole thing didn’t make it into the article, so I’m reiterating it here:

What's simpler than a story about twelve year olds and sixteen year olds in love, and growing up? Is it a race play? I don’t think so. But some people do, simply by the fact that there are people of color in the play. Is it a gay play? Just as much as it’s a Filipino play. But really, it’s a love story. But that's not to diminish those things either. It’s certainly a gay play; it's certainly a Filipino play; it's certainly a Midwest play [where Rey grew up]. But all of those things make it complicated. It’s the simple story of the people we know and their complicated lives. And that, for me, is what makes the great American play. What Rey is doing, he’s doing it for our generation.

If the American theatre scene wishes to participate with the American people, then it needs to do its homework on the reality of the landscape it’s building itself on. In another review of Edith, the writer comments, “Perhaps the playwright is making the point that stories concerning ‘the other,’ need not be about their otherness,” as if it were an illuminating revelation.

…what we seem to be grappling with here is a sense of confusion on behalf of white critics and consumers of art—and that confusion has taken shape in misinterpreting ‘otherness’ as unworthiness.

But that’s just the thing—people of color aren’t going to be “other” for much longer. By 2020, these “others” will make up more than half of the population. Over the next several decades, people like me—those who identify with “more than one race”—will be among the fastest-growing denomination.

When that day comes, where will the theatre community stand? Like Pamatmat said of his playwriting process, what we seem to be grappling with here is a sense of confusion on behalf of white critics and consumers of art—and that confusion has taken shape in misinterpreting “otherness” as unworthiness.

The challenge for the future is for theatre to change its fate. To make sense. To be more real.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here

It's so refreshing to read this because a lot of these things are things I've been thinking and writing about for my play, Encanta: http://www.clydefitchreport.com/2015/04/encanta-as-a-celebration/.

It's disheartening to realize that so many think of our backgrounds and life experiences as limitations rather than enrichments. At the same time, people from the various communities I'm part of have all expressed a keen desire for these kinds of stories: stories about people of color that aren't related to white people, stories about women that aren't related to men, stories about LGBT people that aren't related to straight and cisgender people.

My goal is to try to give such stories to people who desperately need them. If only there was a way to bring the critics along.

I find this conversation to be a much-needed one. As of right now, we are living in a period where artists of color are finally being given the space to tell their own stories, ones that are not necessarily in relationship with whiteness. Unfortunately, there are too many critics and others who have power to delineate what we can consider to be the contemporary theatrical canon that have fallen behind on how conversations about identity work. Just a couple days ago, there was a review of Boston Public Works' production of THREE on The Arts Fuse that, once again, called for an answer to why a woman of color was cast in a play that did not discuss her race.

In the review, the reviewer says, "The character is so amorphous it is difficult to figure out if Jones was cast "non-traditionally"--that is, a black person playing a character who could just as well be white. Or is it that Sam is a black person who only has white friends? If so, why is it that she never once hints at any of the experiences of race that even affluent, educated, African-Americans might share when speaking frankly with their closest friends?" (Check out the full review here: http://tinyurl.com/op3qz5p)

Now, I personally could care less about whether a review is bad or not because I do believe that everyone is entitled to their opinions and criticisms. That being said, after reading these reviews, I, as an actor of color, am forced to ask myself these questions:

1) Will there ever be a time in my career where my being cast in a show will not be dependent on whether or not I decide to tell stories in relationship to whiteness?

2) Will it always be odd to critics for me to get on a stage and depict my experiences with everyday, mundane issues rather than the oppression that I face as a queer Afro-latino male?

3) Lastly, if white actors/characters are not required to discuss their privilege in every play they are depicted in, then why am I required to depict my lack of privilege?

I expect better from contemporary theatre critics. I don't care about their intentions, because whether or not the authors of these reviews intend to belittle the humanity of people of color doesn't matter. What matters is that every time they publish a review like such, they DO belittle the humanity of people of color. This morning, I spilled my tea and broke the coffee mug I was drinking it out of. Sometimes I want to act in a play where my character spills his tea and breaks the coffee mug he was drinking it out of; I cannot create in an industry where my only expectation is that I play a slave or a drag queen. We can do better than that. We NEED to do better than that.