endofplay/7

Gender Stereotypes and Their Subversion

He, the main character of endofplay/7 gets choked up before talking about his brother to his therapist. Finally he delivers what he has prepped as a heavy emotional bomb, “He never liked football, and so, he is sad.” The therapist responds, “It runs in your family, doesn’t it, this sadness and not liking football?” He corrects her: “Deadly strain of not liking football.” The humorous satire on masculinity is just one stop on the wild ride of gender exploration, narcissism, and longing in Chris Danowski’s endofplay/7.

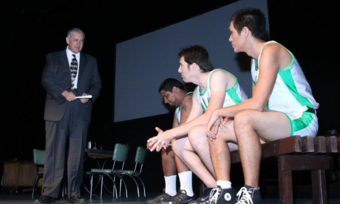

The play’s style and structure is elusive. I would best describe the play, staged in the humble black box of Space 55, as a self-aware dream. A man (He) searches for someone he is missing, or at least, he searches for the meaning behind his nostalgia. Meanwhile, two other women (She and She3PO) have encounters with the protagonist ranging from therapy sessions to sex to picnics as He waxes sentimental, reflecting on his past mate. A dog (Dog) chimes in as comic relief, a sounding board, and a sort-of narrator. Stage directions, which sarcastically poke at the play’s form, are performed by actors (one being playwright Danowski himself), and projected on a screen onstage.

The play, directed by Jake Jack Hylton, balanced, it seemed, between deliberately vague scenes about self-reflection and extremely straightforward explanation. The best example of this juxtaposition might be when Dog first appears onstage. The stage directions are announced, “It’s about goddam time…NARRATORS can at least tell us where to put our eyes at least and make a few little connections here and there so that we can really finally connect the dots. The NARRATOR has also been through all of this and might know exactly how it ends.” Of course, the narrator/Dog responds, “I don’t.” The stage directions continue, “Or perhaps not…they see things we don’t and give us a sense of security.” This same confusion suddenly slashed by a clear point is echoed in the way the play confronts gender issues.

At one point one of the two women shows up dressed in male drag. It’s unclear if she is a new male character or if she is dressing up herself. The stage directions explain, “He is talking to He. Of course they are not the same actor. However there’s no real way to tell the difference between the two and the actors should not try to help.” The gender identity is perplexing, but what’s clear are the direct stereotypes called to attention as the scene progresses. The woman asks He, “Can we please have a real guy conversation, please?” He agrees and She excitedly says “pussy” and guffaws like a stereotypical frat guy.

Presenting stereotypical “guy” conversations and joking that disliking football is deadly for men are just the beginnings of thinking about gender stereotypes in endofplay/7. In a monologue about Rapunzel She mentions cutting her hair, and He responds, “Because you wanted to have short hair like a boy.” She retorts, “Wow, you think boys have short hair.” Most obvious in the direct attention to gender paradigms is the play’s metaphor of ranch dressing. First, She enters a scene in which He is on the ground with his shirt off. She spills ranch onto his chest and states coolly, “See how you like it.” The audience erupted with laugher. A woman squirting white liquid onto a bare-chested man caused an immediate guttural comedic reaction.

Later, He is having a date with She3PO. She shows up to the picnic only to find, “Everything has ranch on it.” (Immediately, my brain went back to what ranch symbolized earlier.) He responds, “Everything is salad because I read that women like salad.” She3PO is not amused and declines He’s request that she start licking up the dressing. Again, the scene is enjoyable in its direct address to gender stereotypes. However, the scene also unsettled me. Similar to the previous ranch piece of the play, I questioned if it is progressive to merely point out a stereotype (perhaps in the name of comedy). Fitting the play’s themes of Lacanian reminiscence, what do we achieve by looking at a reflection of our culture?

I questioned if it is progressive to merely point out a stereotype (perhaps in the name of comedy). Fitting the play’s themes of Lacanian reminiscence, what do we achieve by looking at a reflection of our culture?

I ask these questions not because I thought any part of the play was actually offensive or regressive. I ask them because at times I feel society has moved past parts of gender inequality, but then a quick jibe about men or women generates laughter and makes me reconsider.

When I asked Danowski about the themes I found most prevalent in his work, he shared the overarching intentions of the piece. “My purpose wasn’t to write a play about gender…I was more curious about narcissism and the need to see oneself reflected in another,” he explained. “The guiding impulse, however, in all the drafts, was to consider the nature of projection, the mirror and the other, and to see what that might look like and what it might sound like. Characters change gender fluidly in order to try to find out what it is like to be looking from the outside in, but more, to try to embody the Other (with a capital O), knowing full well that this is very likely impossible.” Indeed, if someone were to ask me to attempt to see the world from a male perspective, I would be hard-pressed to avoid stereotypes. Yet, I simultaneously understand the inherent problems stereotypes cause.

At the end of the play She and She3PO are revealed to be the same woman. My interpretation is that He could never fully pin who he missed, and as a result, created two half-accurate depictions of his (former?) lover. This speaks to narcissism, certainly, but it can also be inferred that this man (and perhaps men in general if we’re exploring stereotypes) can’t tell the difference between very different women. They’re all just women. The message is both startling and old. Yes, generalizing about women is an age-old problem, but do we need to see it on stage yet again? The answer: apparently yes. Every time an audience collectively loves a moment when gender binary is flipped, when the big reveal is a man unable to tell women apart, we learn we still need to see some of these ancient struggles in front of us to learn from them.

In her HowlRound article about the lack of women in Tony nominated categories, Janice Maffei states, “An important first step is to create awareness.” While some may hope our society is past the first step of gender inequality, in many ways, we are still not. As experienced in endofplay/7, we are still exploring inequality, and our findings must be brought to light. While I definitely see the value of awareness in matters of inequality, I maintain we need more steps. If we are satisfied with being aware of problems, we assume someone else will solve them. By acknowledging and then moving beyond awareness into action, we can take personal ownership for the next progressive steps toward equality. So, yes, awareness serves as important soil for gender equality. However, if no action is taken to plant anything in the soil, it remains dirt.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here