Gimme Gimme

the I Want Song in Musical Theatre

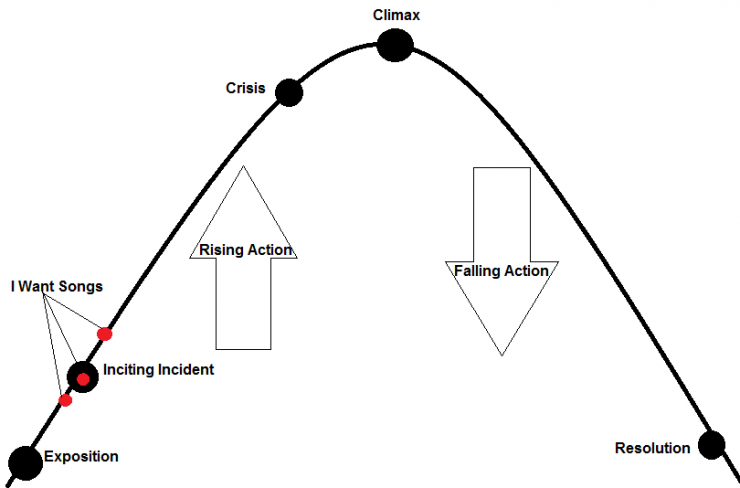

Stephen Schwartz says every good show has one and Bob Fosse says that every third song is one. They’re talking about I Want Songs: convenient forms of character development where the protagonist croons their way through a detailed description of their heart’s desire. I Want Songs tend to pop up in three places in the climactic arc of a musical: before, during, or after the inciting incident.

Shows written prior to the 1960s tended to put the I Want Song just before the inciting incident. Sometimes, as with “Somewhere Over the Rainbow” in The Wizard of Oz, the I Want Song seems to trigger the inciting incident: in this case, the tornado.

Stephen Schwartz says every good show has one and Bob Fosse says that every third song is one.

When the I Want Song falls prior to the inciting incident, the characters make the musical happen. While it would be silly to suggest that “Somewhere Over the Rainbow” causes the tornado, there is a bit of tongue-in-cheek humor in Dorothy’s prayer to the metaphorical sky being answered very literally by a tornado descending from the heavens. Dorothy’s wish corresponds with the inciting incident, which gives her accountability. She wasn’t dropped in Oz at random. Her wish was granted! This makes her mantra of “I just want to go home!” much more poignant because, prior to Oz, she planned to run away.

After the popularity of Oklahoma!—perhaps the most revolutionary piece of musical theatre to date, which premiered in 1943—composers realized that they had to start getting creative if they wanted to compete with Rodgers and Hammerstein. This led to the rearrangement of the classic format and the out-of-the-box structures of Phantom of the Opera, Les Miserablès, Merrily We Roll Along, and Brigadoon. This shift included moving I Want Songs.

Some shows tried putting it on top of the inciting incident. This placement of the I Want Song is the most realistic. It is equal parts character and convenience. Few shows use this tactic because it requires a great deal of masterful set up and exposition, but those that do find that it adds an interesting element of realism in otherwise hard-to-believe situations. Examples include Into the Woods (“I Wish”) and Sweeney Todd (“Priest”) but the best demonstration of this technique is “Put on Your Sunday Clothes” from Hello, Dolly. At the start, Cornelius and Barnaby already dream of getting out of Yonkers. The fact that their boss happens to be leaving—the inciting incident—pushes the two over the edge and they pursue their wish as they form its particulars in “Put on Your Sunday Clothes.” This realism masks the absurdity of the notion that everyone in Yonkers is suddenly sweeping away to NYC.

Finally, the I Want Song may fall after the inciting incident. While the other two placements allow the protagonist to influence the inciting incident, this placement removes that power. Instead, the inciting incident happens to the character and they react to it throughout the show. In Avenue Q, the inciting incident is Princeton’s arrival during “What Do You Do With a BA in English?” His I Want Song, “Purpose,” falls three songs later—Fosse was right—and is a direct reaction to his arrival at Avenue Q. Placed here, the inciting incident creates the protagonist’s objective out of thin air. Childhood dreams, old wounds, deep-seeded desires are impossible in this format because the want is not formed until partway through the show.

The question is, which of these placements works best? Time has proven that the pre-inciting incident I Want Song is the most successful with audiences. It gives the characters the power to make choices and influence the plot. When the characters are making choices, they are more sympathetic. Not only are revivals—which tend to feature I Want Songs earlier on the climactic arc—more popular now than ever, but new material with pre-inciting incident I Want Songs is performing better than musicals with I Want Songs placed elsewhere.

The most recent example is Something Rotten!, a musical that made its Broadway debut in 2015. Parodying the Renaissance, the musical follows Nick and Nigel Bottom as they try to make a name for themselves during Shakespeare’s peak. Along the way, they invent the first musical. The I Want Song falls immediately before the inciting incident. Nick, discouraged with his lack of success, reprises “God, I hate Shakespeare,” and decides mid-song that the only way to outdo the Bard would be to see the future. This gives him the idea to visit a soothsayer, who inspires him to invent the first musical. In this case, the I Want Song causes the inciting incident, which makes the downfall of Nick’s musical Omelet all the more hilarious and heartbreaking.

The only other real contender is the post-inciting incident placement, as I Want Songs during the inciting incident are so rare and can confuse audiences by bombarding them with too much information. The claim to fame of the post-inciting incident placement is the extra emphasis when, typically halfway through the second act, the protagonist is forced to sprout a spine and actually make a choice. This, however, has not proven to resonate with audiences, as shows with pre-inciting incident I Want Songs tend to be revived more and receive more awards: Sweeney Todd (“The Barber and His Wife”), Gypsy (“Some People”), The King and I (“Hello, Young Lovers”), The Sound of Music (“The Sound of Music”), The Drowsy Chaperone (“I Don’t Wanna Show Off”), Bye Bye Birdie (“An English Teacher”), The Phantom of the Opera (“Music of the Night” or “Angel of Music”), etc.

Still, I Want Songs are useless if poorly written. The purpose of the song is to establish the protagonist’s motivation. Aladdin wants to make his mother proud, the Phantom needs Christine to make his song take flight, Quasimodo yearns to live like ordinary men, and Ariel wants to be part of our world. These are specific, solid desires that the characters know are within the realm of possibility. If, however, the I Want Song expresses a vague yearning for change, it can be ineffective and render the song pointless. In fact, without a clear objective, the audience may miss the fact that it is an I Want Song at all.

But the I Want Song did not become a musical must for nothing. When written and placed properly, it is an incomparable tool for character development. It serves as a musical call to adventure. Later, the particular adventure will be incited, but the audience watches as the protagonist becomes ready for whatever lies in store.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here

I really appreciate you writing an article about musical theatre show structure because it’s something that a surprising number of people (even theatre people) don’t really know about. However, as a student of musical theatre writing, there are a lot of strange examples and blanket statements you’re making here.

- “The purpose of the song is to establish the protagonist’s motivation.” Not necessarily true. “I want” songs exist in a larger category of songs called character establishment songs. (“I am” songs are also in this category) Their purpose is to reveal something to the audience about the character. You could call “If I Were a Rich Man” in Fiddler an “I want” song- but it does not establish Tevye’s objective in the show. It has very little to do with the rest of the show. It’s successful because it reveals a hell of a lot about his character – his relationship to God, his wife, what he cares about, etc.

- “When the I Want Song falls prior to the inciting incident, the characters make the musical happen.” Sometimes. Generally, an “I want” song comes before the inciting incident to establish a who a character is before the story gets going. Sometimes the character decides to go and do something after the song (“make the musical happen”) and sometimes things change around them.

- It’s really strange to say that the structure of shows like Phantom, Les Mis, Merrily, and Brigadoon were direct reactions to Oklahoma. Maybe you could argue Brigadoon – but the others were written 40+ years after Oklahoma- a lot had happened to the musical theatre form in those years. Also, Phantom and Les Mis are British Invasion shows- they came from the UK, and in many ways they exist in a category of their own in terms of song and show structure.

- I don’t understand what about putting an “I want” song concurrently with the inciting incident makes it more “realistic.” I also don’t understand why “A Little Priest” from Sweeney Todd (At least, I think that’s what you’re referring to by “Priest”) is an “I want” song. It occurs far after the inciting incident at the end of the first act. (In terms of traditional musical theatre five-act structure, the “third” act). Traditionally, this would be defined as a comedy song.

- I don’t think it’s fair to make a correlation between a successful show (or revival) and the placement of the “I want/I am” song. Most of the time, those shows are successful because they are well-written for 1,000 reasons- the placement of the “I want” song being 1 of 1,000.

- “If an I Want Song expresses a vague yearning for change, it can be ineffective and render the song pointless.” I think both “Something’s Coming” in West Side Story and “Corner of the Sky” in Pippin are about vague yearning for change, and both of them are great because of the specificity of the (baseball/nature) imagery in the lyrics.

You're very insightful. Thank you for your feedback.

What are the baseball allusions in "Something's Coming"???