Pause, Move Forward

Physicality and Inner Strength in Colossal

To celebrate the 25th anniversary of the Americans with Disabilities Act on July 26th, we're publishing a series of pieces focusing on issues of accessibility and visibility in theatre.

“That split second…that flash…you think you’re dead…but you’re alive.”

To enter onto the stage of Boston-based Company One’s production of playwright Andrew Hinderaker’s passionate, shattering work, Colossal, is to enter onto a set that isn’t quite a set at all.

I played varsity sports in high school—shocking, I know, for those who know me. Whatever time wasn’t spent training for the grueling lacrosse season involved hitting the track over and over again to prepare for cross country.

What I remember of those high school sports isn’t pretty. First, there’s the pain. Constant and pulsating like a heartbeat, it was a reminder: I needed to be faster. Better. Stronger. Second was the expectation: my teammates depended on me, and it didn’t matter how tired I was, didn’t matter what emotional burden I may be carrying, didn’t matter whatever else was on my mind that day or night—above all, I needed to play. Hard.

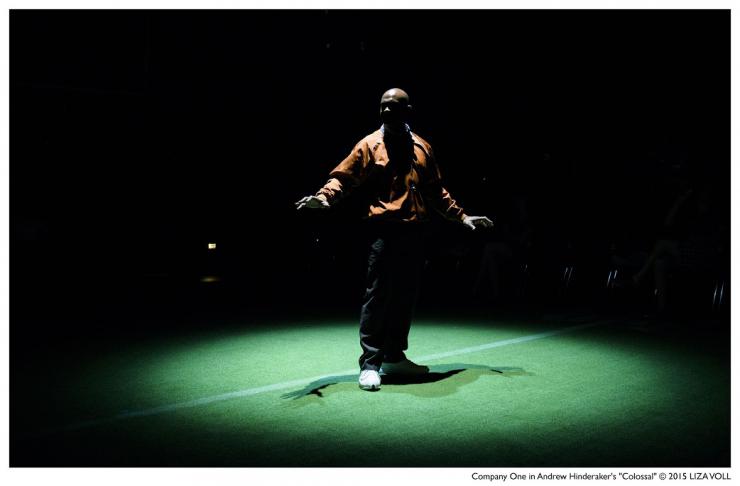

A second after walking into Colossal, it all came rushing back—because this wasn’t a play, it was a football practice. The team’s coach (Damon Singletary) barks familiar orders as the audience files in, skirting the Astroturf floor to sit in the “bleachers.” Workout music blasts from the venue’s speakers, and a scoreboard counts down the time until the game is set to begin. The smell of sweat hangs heavily in the air, every breath catching with concern as the players expertly throw footballs to each other in speed drills, and move with practiced precision through a variety of agility exercises, from lunges to sprints.

The entire work is built like this—it plays out in four quarters, including a halftime show, and even involves a drum line. The effect is immersive, nostalgic, brimming with physicality—and a fitting juxtaposition that lays the groundwork for the show’s deceptively straightforward premise.

From the very first scene, we know exactly what this play is about, as Mike (Marlon Shepard) moves deftly among the players on the field in his wheelchair, remote control in hand. Pause, rewind. Pause, rewind. He examines the field from every angle, his past, able-bodied self included, never moving forward—always going back.

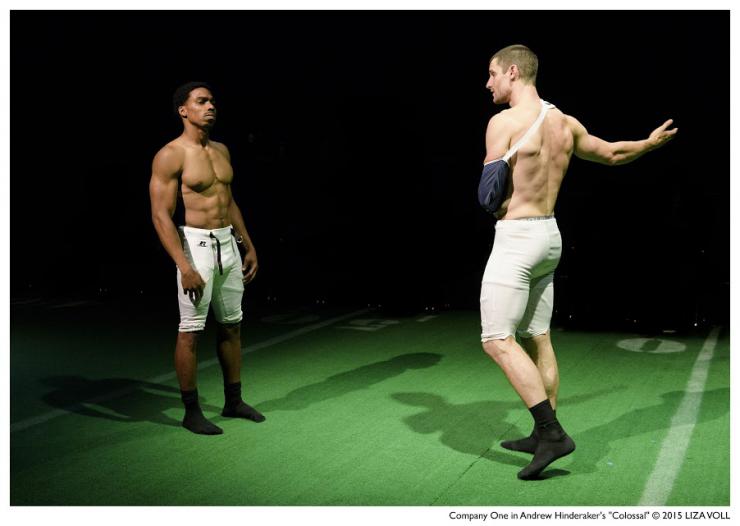

Then comes the surprise: Mike is in love with Marcus, another player on his team. On the field, they move fluidly together, nailing seamless plays and surely destined to go pro. Off the field, however, the dynamics of their relationship tell a much more complicated story, as they deal with societal pressures of traditional masculinity, come to terms with their identities, and find themselves going to great lengths to hide their relationship from the rest of the team.

Shepard is a competitive, experienced athlete, and before appearing in Company One’s production, he completed their Professional Development for Actors class. His inexperience shows, but in a way that adds a layer of depth to his character. He plays a man who dreams of a future filled with personal and emotional victories, but who’s been let down by every man he’s ever trusted or loved. The very act of touching sends Mike recoiling in his chair.

Shepard’s delivery struggles with the stoic language of a man who’s been utterly stripped of his confidence and livelihood—and it lends a real feeling of innocence and earnestness that is completely devoid of the dramatic elements common in a theatrical performance. This is no flowery-tongued, special-effects-laden work. This is football. This is reality. This is raw, human, stumbling, staggering truth. It asks: Can you be no place but here? No time but now? Will you live in this moment?

This is no flowery-tongued, special-effects-laden work. This is football. This is reality. This is raw, human, stumbling, staggering truth. It asks: Can you be no place but here? No time but now? Will you live in this moment?

The most powerful scenes in Colossal are those that showcase the juxtaposition of testosterone-fueled physicality with unattainable dreams and fictions we build to comfort ourselves. Parallels of practice and physical therapy depict the man Mike is with the man he used to be (played by the exuberant, cocky Alex Molina, a college football player turned European pro and recent MFA graduate of the A.R.T. Institute at Harvard). Our bodies are vehicles, the play reminds us, in words and in actions. What do we do when these vehicles inevitably fail us?

At its core, this is a play about the lies we tell ourselves in order to carry on. It’s about the expectations we build up, praying that the wrecking ball of reality will spare, for just a few more moments, our carefully constructed paper houses. We can’t put all of our self-worth into our bodies. We definitely can’t place it into others. At the end of the day, we have to find the strength to face our personal tragedies, and find resilience within.

Moreover, Colossal examines the limits of what a stage play is meant to be. It creates a world, a space and time, removed from whatever lives we left behind when we entered the venue. It allows us to access this place, to get on the same level as these characters, and to utterly invest ourselves in the story unfolding before our eyes. I’m struggling to find the words to describe just how it felt to walk into that venue—to emulate the immediate sensual onslaught that transported me right back to the fields I played on years ago. So I’ll tell you what I felt: the anxiety, the anticipation; the smell of turf and sweat and even a little fear; the knowledge that, for the next hour, all eyes would be on me. What was I going to do with that? What else is there to do, but perform?

As a dramaturg who identifies as bisexual, I want to see more stories of people like me on stage.

For Mike, the crux of his own development lies on one simple yet devastating act—what will happen when he chooses to finally move forward, instead of pausing, instead of going back? When we choose to embrace our pain instead of pushing it away, what power and freedom will we find there?

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here