That’s Entertainment? Seven Lessons Playwrights Can Learn from Postmodern Philosophy

You might be like me. You may feel like a lot of theatre doesn’t reach you because it’s designed to impart a monolithic pronouncement of a moral or political “truth” on you without letting you put the pieces together yourself. You may wish to use this line of thinking to help your own plays, seizing control of the tools that other authors use to tell you what to think. You may even want to create work that makes space for the dismantling of your own text in order to give your audience the freedom to do what they want with it.

But you may not know where to start. If, and that’s a big if, this is the case, allow me to share with you seven lessons playwrights can learn from Postmodern philosophy.

If you want to write work that mirrors the real world as closely as possible, why not try including as much raw information as you can?

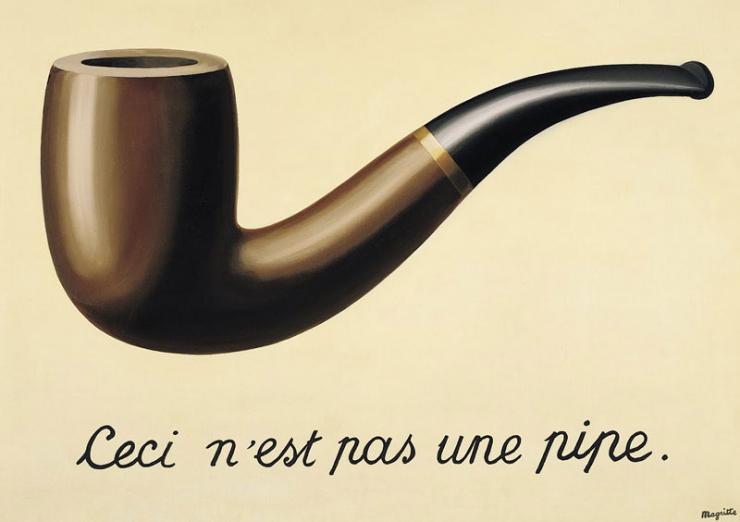

1. Ditch the idea that the purpose of writing is to reveal truth.

Postmodernism is concerned with the ultimate fallibility of objective truth. According to Jean-Francois Lyotard, these truths most often come in the form of “metanarratives”—grand narratives like “the American dream” that are repeated to teach the culture at large the purpose of their actions. Instead of writing to uphold a cultural myth that tells you how to live your life, recognize it’s a totalizing statement that you have no way of proving beyond your own experience. Forget about trying to include a moral to your story, but instead, write to express yourself.

2. If nothing is “true,” everything is permitted.

Since you recently discovered you’re no longer required to reveal any sort of true statement with your art, feel free to mess around with narrative possibilities that might not make sense when viewed through the (fallible) lens of accuracy. Take a page out of Lin-Manuel Miranda’s Hamilton, which uses Hip-Hop and nontraditional casting to reject the metanarrative of Alexander Hamilton’s life in favor of a more personal story, which values cultural pluralism over a monolithic understanding of a national founding myth.

3. There is no such thing as “high” or “low” culture.

Postmodernists don’t believe any group has the right to use their nonexistent authority to impose a hierarchy on cultural tastes—all taste is uniquely subjective. Because of this, the lines between elite culture and popular culture are rendered nonexistent. So, feel free to take on whatever subject you want no matter how stupid it may seem! Take Anne Washburn’s Mr. Burns for example. She explicitly eliminates the dichotomy between “high” and “low” art by showing the social history of a single episode of The Simpsons, which is elevated from a mere TV episode into a religious ritual over the course of a thousand years in an imagined future.

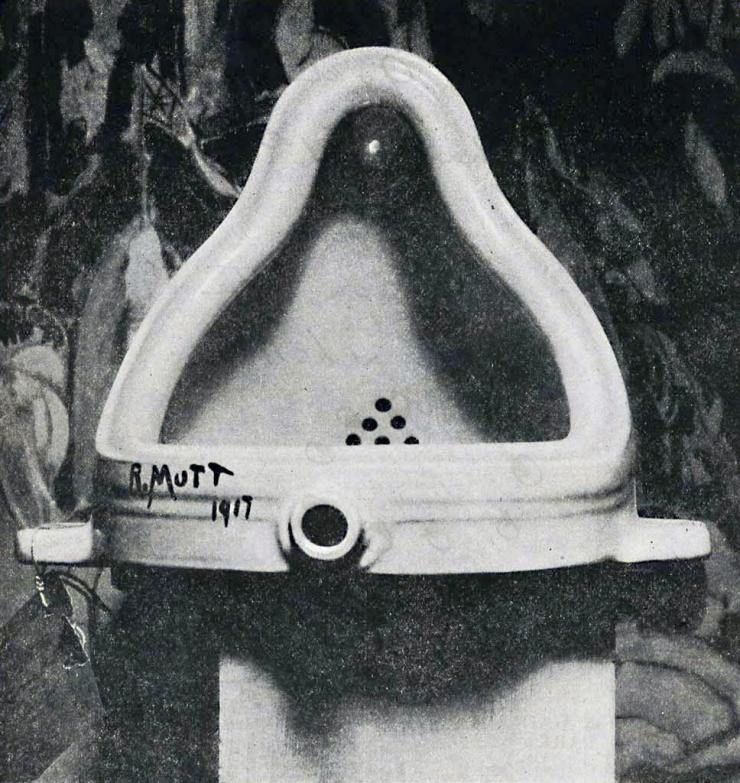

4. The limits of your invention are not housed within the text!

Since the only things that dictate an obligation to preserving the integrity of any text are our own metanarratives of “originality,” feel free to push them to the side. According to Roland Barthes, the meaning of a text (read here: a play) isn’t housed in the text itself, but in the head of the audience member viewing it. And even then, the play is only in relation to every text that audience member has ever interacted with. Now that you’re a postmodernist, you’re allowed to cut that text up. Don’t just set Shakespeare in a different time period to put your own authorial brand on his work. Add scenes! Remove lines! Insert new characters, or create a new play entirely. Authorship doesn’t mean originality. In the age of mass produced entertainment, there is no such thing!

Due to the instantaneous transmission of information in contemporary society, we often forget we are detached from the outcomes of most events we observe.

5. Let Wikipedia Write Your Plays for You!

If you want to write work that mirrors the real world as closely as possible, why not try including as much raw information as you can? It’s not boring, but representative of our modern condition that consists of omnipresent, unending data. Lyotard notes that knowledge has become stripped of any attachment to the progress it once may have had. There’s a reason for endurance. Maximalist theatre has never been more popular. Shows like Gatz, Wolf Hall, All Our Tragic, and the Lehman Trilogy aestheticize ancillary details and make facts exciting. Thus, take the burden of understanding all that information off of the audience, and let it wash over them like a shower.

6. Break the Fifth Wall!

Due to the instantaneous transmission of information in contemporary society, we often forget we are detached from the outcomes of most events we observe. All our outrage on social media equates to nothing more than the indifferent passivity of an industrialized population according to French Philosopher Jean Baudrillard. Suck your audience out of “the Matrix” by forcing them to directly participate in the outcome of your play’s action. Punchdrunk’s Sleep No More famously does this by allowing their audience free reign to walk around their site-specific rendition of Macbeth. Audiences can view each scene in any order they choose and interact with the performers as much as they’re comfortable with.

7. Ignore this Article!

Postmodernism is famous for its skepticism when it comes to the idea of revealing any form of objective truth. It rejects the idea of language, seeing it as nothing more than an oppressive tool for controlling the masses. Postmodernism also rejects the idea of theories because ultimately, no theory can be proven more correct than any other. By its own criteria, postmodernism frequently disproves itself, and this article shouldn’t be any different! If these ideas don’t work for you, chalk them up to an oppressive author telling you how to think by housing you in his inflexible personal philosophy. Then, write whatever you want anyway!

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here