Anywhere and Everywhere

Orientalism in Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus

This spring, Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus received widespread media attention as it retired its performing elephants to a conservation center in Florida. The process of ending the pachyderms’ run was announced last year and slated to take place gradually through 2018, but in January, Feld Entertainment, owner and operator of RB&BB since 1967, announced the elephants would retire to Florida ahead of schedule. The circus live-streamed the elephants’ final performance on Facebook and its website, and circus historians (with varying degrees of wistfulness) called the decision the end of an era. Animal rights activists welcomed it but bemoaned it as woefully late.

The ASPCA, PETA, and local protesters agree that the retirement of only the elephants from RB&BB’s extensive menageries does not end the circus’s exploitative practices (though camels, llamas, and fat pigs have not invoked the same apprehension or aroused the same emotional attachment as elephants). I suggest The Greatest Show on Earth remains problematic for a reason that receives no such headlines as the elephants received: the circus presents non-Western human performers with colonialist trappings of orientalism and turns them into long-perpetuated and fetishized stereotypes.

RB&BB presents performers from “The East” with orientalist frills that have nothing to do with the acts themselves. The ways in which RB&BB presents these acts replace performers’ cultural backgrounds with occidental fantasies of the “Orient.”

For decades RB&BB circuses have included performers from around the world, but its most recent tours, Legends (which I saw in October 2015) and Circus Xtreme (May 2016, both at the Verizon Wireless Arena in Manchester, New Hampshire), offered egregious examples of cultural erasure. (Legends closed in May as the elephants retired. Circus Xtreme, now sans elephants, tours through September.) Unlike some nineteenth- and early twentieth-century “foreign” entertainers (Chung Ling Soo, perhaps most famously), these acts are not performed by white actors in (pick a color)face. Members of the China National Acrobatic Troupe, for instance, are indeed Chinese; the Mongolian Marvels, a team of strongmen and contortionists, are indeed from Mongolia. Yet unlike other non-American acts, such as Spanish high-wire walkers, Ukrainian trampoline jumpers, Paraguayan motorcyclists, and French aerialists, RB&BB presents performers from “The East” with orientalist frills that have nothing to do with the acts themselves. The ways in which RB&BB presents these acts replace performers’ cultural backgrounds with occidental fantasies of the “Orient.”

That is how Edward Said defined orientalism in his groundbreaking and highly influential Orientalism. Said argues that modern orientalism began in the eighteenth century as the dawning age of empire produced a profusion of intercultural contacts among Europeans and other peoples across the globe. (He also points out that orientalism roots Aeschylus’ The Persians, the oldest extant Western drama.) Since the book’s 1978 publication, scholars have added important nuances to Said’s proposals—especially since 9/11—but it’s worth revisiting Said’s original findings to understand the processes at work in RB&BB.

For Said, orientalism is a hydra that rears its heads in the arts, in commerce, and in the academy, but most significantly orientalism is “a political vision of reality whose structure promoted the difference between the familiar (Europe, the West, ‘us’) and the strange (the Orient, the East, ‘them’),” Said writes in his first chapter. But orientalism involves not only exploitation; it relies on invention. Also from Said’s first chapter: “It is Europe that articulates the Orient; this articulation is the prerogative, not of a puppet master, but of a genuine creator, whose life-giving power represents, animates, and constitutes the otherwise silent and dangerous space between familiar boundaries.” Said references Europe because he suggests that that continent’s brands of orientalism derived from relationships with the Middle East and Northern Africa. Said suggests American orientalism has largely concerned Asia and the arrival of immigrants across the Pacific—a contention borne out in federal policies from the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act to the World War II internment of Japanese Americans. Whether it was the Europeans’ consideration of the Middle East and Africa or Americans’ of Asia, orientalism erases the real by creating the false.

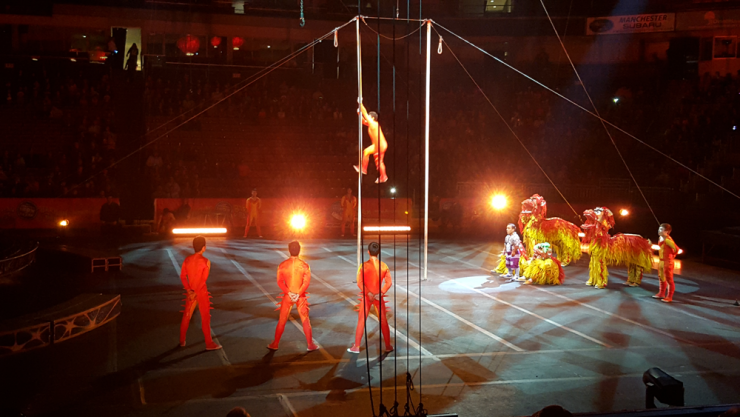

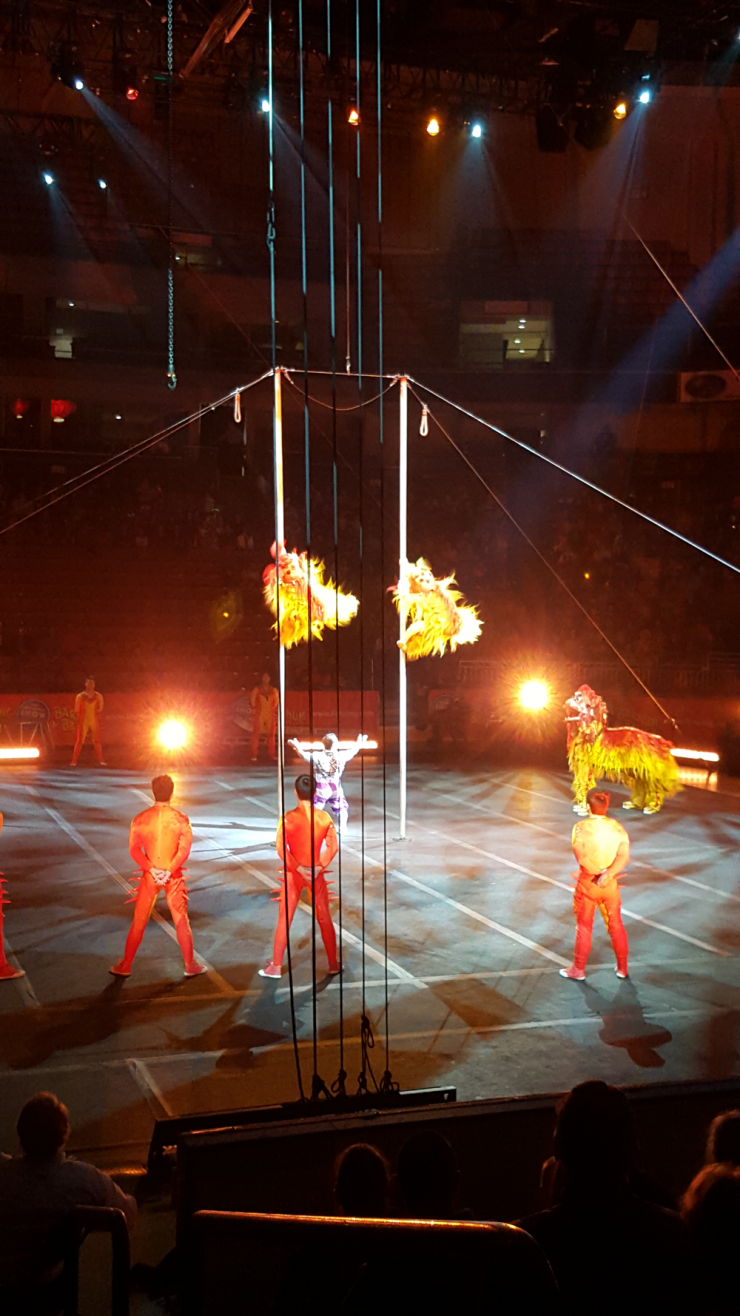

Such creation is evident in RB&BB. Legends features an extended act by the China National Acrobatic Troupe. Women juggle diablos, a kind of large yoyo that spins and balances on a string. The performers are costumed in the colors and feathers of peacocks, which are not indigenous to China but have important roles in a variety of non-Western religions (and their Western perceptions). The women fling the things high in the air. They somersault and catch them. They toss them back and forth. In another portion of the act, male tumblers leap through the spinning rings of a robot and vault themselves ten feet in the air. In another portion of the act, acrobats ascend vertical poles and leap between them. Two performers dressed as guardian lions participate in the acrobatics; two more look on and prowl the floor, all while Chinese-inflected bells, flutes, and drums play. (Curiously, Paulo Cesar dos Santos, a Brazilian Capoeira expert and little person, enters astride one of the lions and joins the troupe in some of their feats.)

In the souvenir DVD of the show, the ringmaster narrates the performance, noting, “Many acrobatic acts originated in China’s Han dynasty, an era of unsurpassed golden riches, more than 2,000 years ago. According to local folklore, true riches cannot be attained without true discipline.” The statement is largely accurate in its chronology, though acrobatics may predate that third-century-BCE dynasty. (Diablos are also thought to date from the same period.) The difference between the live performance and the information added in the DVD is striking in the former’s conformation to a Western rendering of “China,” created with a few Chinesish markings in the music and with the lions. Circus audiences aren’t provided the (however meager) historical context narrated in the DVD; instead, the primary accoutrements of the acts are the sights and sounds of orientalist shorthand. But even in the video, the suggestion that “golden” and “true riches” are an ultimate goal underscores the West’s financial preoccupation with Asia, as demonstrated by the travels of Marco Polo, Christopher Columbus, Commodore Perry, among others and beyond.

Sandwiched between performances by the Angelic Aerialists and the Mongolian Marvels, a pageant of chinoiserie and Arabesque nonsense swarms the arena floor, complete with exaggerated lanterns, vests that could have been swiped from Aladdin, a pagoda umbrella, tinkling bells, and a red-nosed swami-clown whose only jobs seem to be to tote around a fortuneteller’s table and make vaguely non-Western hand movements.

The DVD narrator adds, “Guardian lions are believed to have many mystical and protective powers, and it is for this reason they are placed outside important buildings throughout China. Can they protect Paulo?” Again, there is accuracy enough in the general description of the lions’ relevance in Chinese culture and history, but RB&BB has them aspiring to protect dos Santos, who is not a member of the troupe, who is actually not much smaller in stature than the acrobats, and whose presence serves to highlight just how “foreign” the Chinese troupe is.

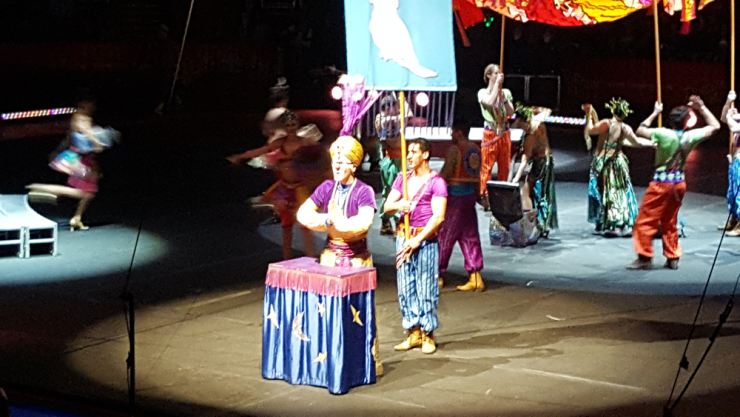

In RB&BB’s current tour, Circus Xtreme, a frightful example of orientalism comes midway through the circus’s first act. Sandwiched between performances by the Angelic Aerialists and the Mongolian Marvels, a pageant of chinoiserie and Arabesque nonsense swarms the arena floor, complete with exaggerated lanterns, vests that could have been swiped from Aladdin, a pagoda umbrella, tinkling bells, and a red-nosed swami-clown whose only jobs seem to be to tote around a fortuneteller’s table and make vaguely non-Western hand movements.

The cavalcade of imperialist hokum also features a genie who strolls about with a lamp. “We’ll find the best belly dancers,” the ringmaster sings, as the largely white dance troupe does everything but belly dance. A scantily clad snake-charmer makes an appearance; not incidentally, editions of Said’s Orientalism feature Jean-Léon Gérôme’s The Snake Charmer on their covers.

Throughout the colonialist mashup, the ringmaster sings one of the show’s signature songs: “From anywhere and everywhere to The Greatest Show on Earth…” RB&BB has done us a favor then, in their daring and adventuresome quest to go out and find for us the greatest acts on earth. This is the conceit of Circus Xtreme. The show’s loose plot centers on Alex and Irina, two animal trainers; the pair, originally from Moscow, have scoured the earth on behalf of RB&BB to find the most exciting performances. Now, with the help of the ringmaster, they parade before us Mongolian camel-riders, Chinese acrobats, a Chilean lion-tamer, and the wheel-of-steel daredevil Benny Ibarra, who is from Mexico City but was introduced by the ringmaster at the performance I saw as having been found in the wilds.

To be sure, American BMX riders (primarily white) also perform in the show, and Clown Alley has become increasingly more diverse. But the concept of Circus Xtreme, which offers American audiences the opportunity to be entertained by “foreigners” is just another installment in the profit-making schemes that gave the world the Venus Hottentot, the original “Siamese twins,” and P. T. Barnum’s “What Is It?” Said introduces orientalism as “a Western style for dominating, restructuring, and having authority over the Orient.”

What’s remarkable about this imperialist spectacle is that it is unnecessary: the physical performances should suffice; trick-riding on camels, lifting five hundred pounds with one’s teeth, leaping unassisted through rings stacked ten feet in the air are all “xtreme” enough feats to entertain and awe. But the lure of the Orient remains powerful, four centuries after its modern advent. “You ain’t seen nothin’ like this,” sings the ringmaster in Circus Xtreme. Unfortunately, RB&BB’s uses of orientalism align closely with versions of the “Orient” which for centuries of imperialism Westerners have reimagined. The circus claims to have been everywhere and anywhere, but it’s been nowhere at all. RB&BB’s next show, Out of This World, begins a two-year tour this summer. Its conceit is an intergalactic battle that pits good against evil. I can’t wait to see who’s who.

Special thanks for Katherine J. Swimm for suggesting this article’s title and to Hesam Sharifian for chatting about Said.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here