The Status Quo

In a substantial number of educational costume programs across the country, history is included as a core aspect of the curriculum. However, it is often constrained to a single sixteen-week semester or lumped in with the study of architecture and decorative arts. When tasked with teaching dress through the entirety of human history, an instructor must carefully curate and format their delivery to cover as much information as possible in the shortest amount of time. For many, the initial approach is teaching the way they were taught: a chronological, linear walkthrough of the major eras of Western history, supported with a textbook and image slides to memorize.

This model has become the de facto method for historical teaching in fashion and the arts, but it does not afford much room to acknowledge or honor the cultural contributions and lived experiences of much of the globe. Indeed, the very idea that there is only one way to learn, one way to think, and one correct answer to every question is a problematic concept—and a hallmark of white supremacist culture. We must reorient our pedagogy if we are committed to anti-racist training.

What if we dismantle the structure altogether and look through a new frame? As costume designers and practitioners, we continually apply our knowledge of historical dress to create costumes that convey story, mood, and character, so a perfunctory memorization of silhouettes and dates is not enough. In order to gain a more dimensional understanding of history and the entanglements of cultures and eras, we must seek and examine primary sources and varied narratives. We must inquire and examine the “who,” “why,” and “how” of history, not just the “what.” By teaching history as something to investigate, not memorize, we can empower our students with the ability to engage deeply with historical dress and make design choices that are not merely historically accurate, but that enhance the storytelling in productions.

The very idea that there is only one way to learn, one way to think, and one correct answer to every question is a problematic concept—and a hallmark of white supremacist culture.

Fresh Strategies

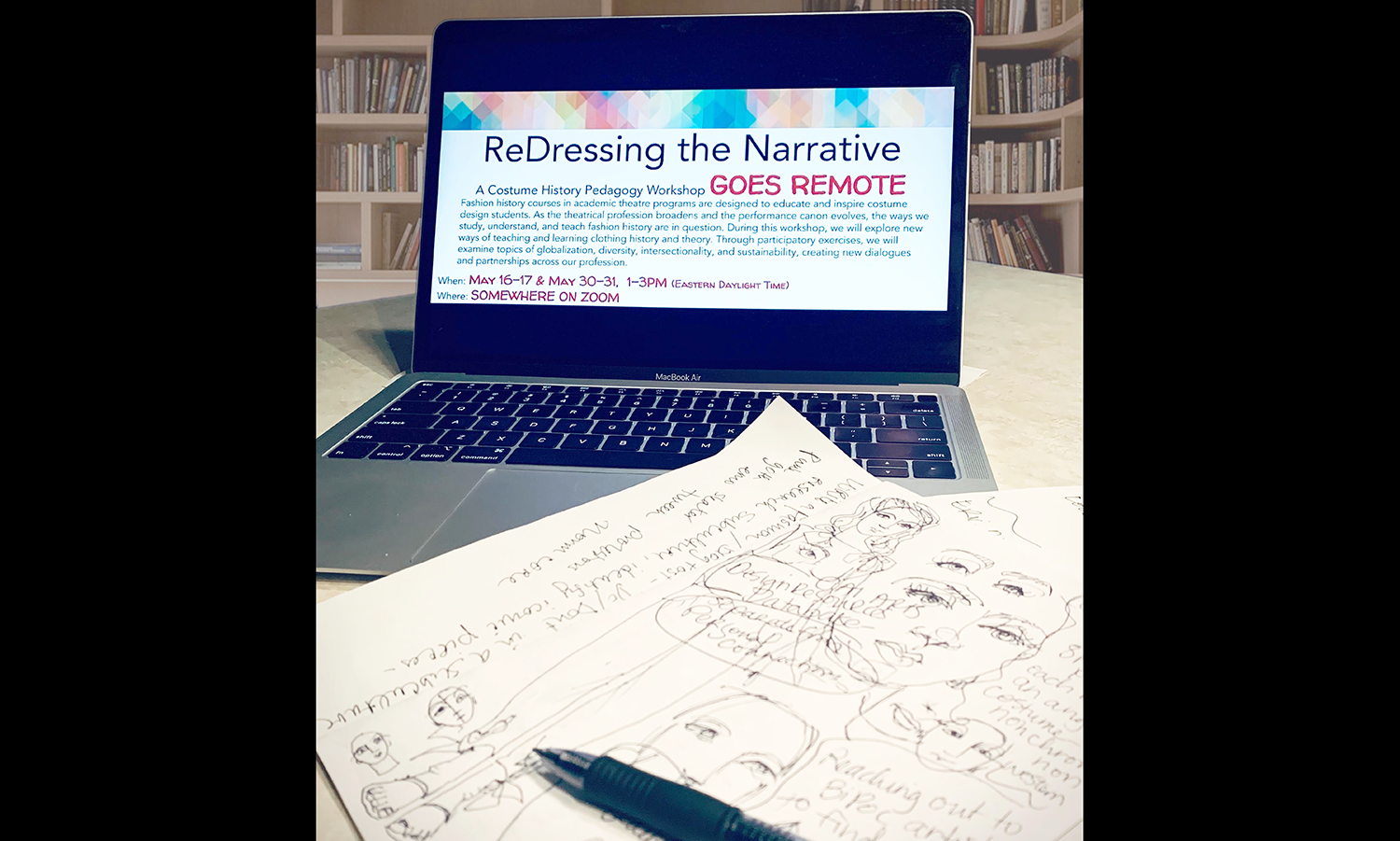

Frances McSherry, teaching professor at Northeastern University, and Eric Abele, lecturer in costume design at the University of Maryland, Baltimore County—both participants in the ReDressing workshop—are already putting some of these concepts into practice. In an online presentation in early August, each of them shared their experience reconfiguring fashion history courses over the summer. Both educators modified their past approach by centering concepts rather than dates and titles. As McSherry, Abele, and others begin exploring potential organizing principles for course design, several major strategies are emerging.

An entire course can center around specific questions: “Why do men and women dress differently?” “Where does our clothing originate?” “How has the body been presented differently in different cultures and eras?” The central questions become a throughline that engage students to apply history and find the answers. We can continually return to the core questions as we examine particular periods and cultures. By shifting from a traditional model of information delivery and instead centering inquiry, we can stimulate students’ curiosity and can equip them to discover the answers.

Another strategy is to divide the course into thematic sections. Abele has developed an approach that centers around four themes in costume history: protection, sex, status, and expression. He leads his students through conversations about each theme, which offer the opportunity to explore connections among a range of topics, including Indigenous cultures, gender expression, conspicuous consumption, and cultural appropriation. Other thematic structures might focus on different garment types (pants, suits, underpinnings), garment shapes (rectangles, triangles, curves), or body parts (head, shoulders, waist, derriere). Offering historical garments from varied cultures and eras and studying how these themes resonate through time helps students discern the commonalities and differences in different systems of dress.

Examining clothing history through an interdisciplinary lens, another strategy, aims to find links between clothing and a variety of academic studies. Approaching history through theories originated in the fields of gender studies, LGBTQ studies, anthropology, material culture, sociology, or geography can help add nuance and depth to students’ understanding of historical clothing. Chatterjee folds concepts from postcolonial and decolonial studies into her courses, partly focusing on fashion from the Global South as a framework for investigation. This strategy aligns with the growing interdisciplinary push on many campuses.

Staying focused within our own discipline, it might help to remember the root of all drama: conflict. Theatremakers are well versed in studying dramatic structure and identifying the major conflicts in a text, so why not apply the exercise to history? We are well equipped to study clashes between empires, human rights issues, and fights for social justice. History is a series of causes and effects—it is full of dynamic struggles and shifts in power. Indeed, dress is often linked to societal and cultural shifts, as we see in the French Revolutionary era, for example, when knee breeches were rejected in favor of long pants for men. Social justice protestors in 2020, too, have been choosing their clothing to communicate their struggle against racism and systemic inequality. A course structure that prioritizes connections between clothing and conflict can inspire investigation into costume’s relationship to conflict.

Another strategy, offered by Muller in the May workshop, eliminates the pressure to cover the entirety of costume history: choosing one specific era or event and centering projects and assignments around a deep research dive. A thorough investigation of one specific topic teaches students how to perform robust, quality research, and teachers can guide them to connect their findings to other time periods and historical concepts, including influences on the world today. An added benefit of this strategy is that it reinforces the importance of engaging with a variety of sources and pushing beyond the information that is most readily accessible.

Offering historical garments from varied cultures and eras and studying how these themes resonate through time helps students discern the commonalities and differences in different systems of dress.

Inclusivity in the Classroom

Potentially one of the most salient themes (“unprecedented and paradigm-shifting,” to quote a participant) to emerge from the ReDressing workshop is the transformative idea, presented by Chapin, that leadership does not require absolute expertise. Educators no longer need to perform as the “sage on the stage” and deliver answers to students in the classroom, and in fact this model can be damaging in ways to instructors and students alike. By rejecting the false presumption that educators have all the answers, we can feel empowered to lead with empathy and awareness, and to embrace the idea that there is no “correct” way of thinking, designing, or making. If the instructor does not have a monopoly on the truth, students can be empowered to bring their ideas and lived experiences into the classroom, creating a culture of mutual support that equalizes the typical power structure.

Fostering inclusive classrooms is an ongoing goal for Myers. A primary way to cultivate this environment is to focus on empowering students and giving them more control of their own learning. Developing a course based on learning outcomes is one student-centered way to approach class material. Choosing more active learning objectives (“investigate” or “examine” rather than “memorize” or “define”) can open the door to fresh methods of delivery and give students more ownership of their learning. During “ReDressing the Narrative,” Myers also presented the concept of trauma-informed teaching, which prioritizes the creation of an equitable learning environment so that all students, no matter their background or experience, can feel valued and supported in the classroom.

Challenges and Opportunities

This work can be uncomfortable, because our own past learning is often deeply ingrained. Such a fundamental change in course organization requires us educators to radically reorient our own scaffolded understanding of the material. However, even small shifts in the way we deliver our courses can have an impact. Rewriting an entire course is a huge commitment, but changing a module or a few learning objectives each semester can be a measurable and meaningful step toward comprehensive change.

In this particularly strange time of pandemic, social upheaval, and the near-complete shutdown of our industry, we have been given the opportunity to make space for deep reflection—a luxury among theatre practitioners who usually measure time in relation to the opening-night deadline. A non-stop production schedule leaves little room for the contemplation of theories and innovative thinking, not to mention the ability to share that thinking with others. Consequently, it is incredibly difficult for many costume designers and technicians to focus on scholarly research or to examine pedagogy. The current lull in production allows us to dedicate more time and energy to connecting with peers who are tackling the same problems.

As a result of Chapin and Myers’ “ReDressing the Narrative” workshop, countless fires have been sparked among participants. With great generosity of spirit, we have begun to share our individual ideas, research, and resources. Lists of culturally inclusive play scripts with interesting costume challenges, diverse research sources and techniques, publication opportunities, pedagogical strategies, and more sprung from the group and continue to develop. At the close of the workshop, an executive committee was formed in order to formulate strategies for the future impact of the group. Moving forward, one of our major goals is to develop and disseminate these resources, housing them within educational institutions that have the ability to support our research. We continue to cultivate meaningful connections between members of our discipline and work toward dismantling the pedagogical status quo.

Gathering in a virtual room full of costume experts illuminated the value of collaboration in making real, substantive change in our institutions, moving forward with a shared goal of a more inclusive theatre. It was the shovel-in-the-ground moment, establishing an active community eager to combine resources and build a platform for revolution.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here

It was a terrific workshop and this a good article. I’m on class 2 of my new syllabus, so far so good! Looking forward to the next workshop!

Thanks for this!! A terrific and much needed piece to address the ways in which costumes (and all design areas) are not "neutral" in the fight for anti-racist representation.