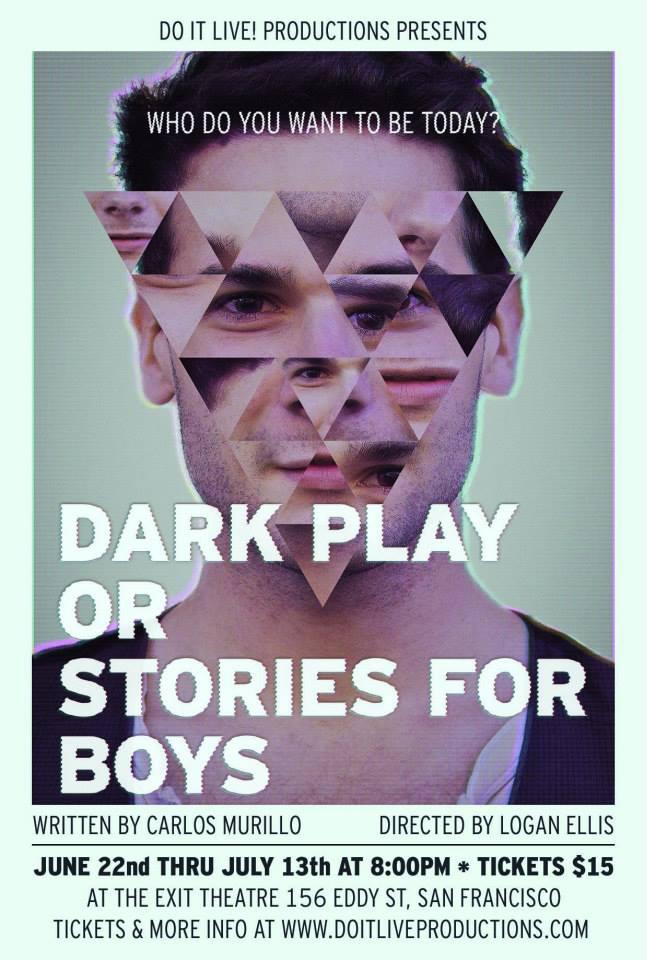

Dark Play, or Stories for Boys

Playwright Carlos Murillo says that his 2005 play Dark Play, or Stories for Boys, now in a Do It Live! production, takes place “now,” but I’d place it more in 1997. The play is steeped in the world of the interwebs, but in younger, fresher days, when it might still have been called “the net,” when AOL reigned supreme and “You’ve Got Mail” was ubiquitous, when you encapsulated your identity in screen names like “SOCCERDUDE2891” instead of on your Facebook profile, when chat rooms flung together people with nothing in common but their internet connections, all bewildered but hopeful, fresh faced and doe-eyed as the ‘net itself.

Nick (Will Hand) is a product of this world, but he’s also a part of a long tradition of outsiders like, most recently, Jesse Eisenberg’s rendering of Mark Zuckerberg in The Social Network or Lisbeth Salander in The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo. These characters, ostracized by the real world, seek prestige or revenge in the virtual one. Once rejected, they are now ruthless. They show no mercy as they manipulate, sublimating all compassion, until, later, they again seek out something human and are crushed.

These characters are the killer nerds.

These characters are the killer nerds.

Killer nerds are cautionary tales twice over. First, they show us the consequences of marginalization in a world in which it’s too easy to be forgotten. Second, they play on the anxiety well-trod in sci-fi about the growing power of our technological advances: Might our devices be able to hurt us?

When Nick walks on, his button-down cardigan and thick glasses (costumes are by Ashley Rogers) identify him as nerd; his first line, astutely delivered by Hand, who eerily raises alternate eyebrows with the clockwork regularity of the machine Nick will become, identifies him as a killer nerd:

I make shit up.

I make shit up all the time

partly cause I like making shit up

partly cause I’m good at it

partly cause

well

I can.

Nick is quiet in real life, he says. “Other kids were used to not noticing me, flying as far under the radar as I did in school.” But online, he has the social prowess of a Mean Girl, assembling or clearing chat rooms on a whim, shape shifting with the few keystrokes it takes to coin a new screen name. For much of the play, ability is the beginning and end of Nick’s motivation, but he doesn’t challenge himself with difficult targets; rather, he selects the easiest ones and challenges himself by seeing how far he can take his lies, with no other object than, as Nick says, “digging into the murky recesses of human nature,” to “see what people were really made of.”

He’s both intrigued and disgusted by Adam (Adam Magill) because of six words Nick discovers on his profile: “I want to fall in love.” That, for the preternaturally jaded Nick, signifies that Adam ranks 10 on the “Gullibility Threshold.” Magill, for his part, delivers Adam’s lines with earnestness, yes, but it’s too pure to laugh at. When he protests, “I’m not stupid!” he is crusading for his right to believe. This, for Nick, constitutes “the murky recesses of human nature,” which he plumbs by creating Rachel (Amy Nowak), who corresponds perfectly to Adam’s demands:

I want to fall in love with a girl...

15-18. Would like her to have green eyes, dirty blonde hair,

she should be like 5’4”, 5’6” tops,

have a good body (no fat girls, please, no offense)

she should be smart and likes to chill on the beach.

Part of what’s intriguing about the killer nerd character type is that it, despite deep flaws, it’s sympathetic. Nick, for one, is cruel and condescending, but he’s not purely evil, largely because, as the play progresses, he’s less disgusted by Adam than he is intrigued—sexually.

Nick is clear-sighted enough to see his flaws. “I sure as hell recognized the darkness and danger lurking in my soul,” he says. “I couldn’t do shit to change it.” He knows he doesn’t have the ability to woo Adam the way Adam wants to be wooed, both because Nick’s not a girl and because he can’t speak Adam’s language of pure love without the insulation of several layers of disguise or irony.

But oh, can he fake it. Nick, in fact, is a master of language, conveying his thoughts with pith and wit:

Adam, like pretty much the rest of us,

was a belief-starved kid hopscotching across the 500 channels of satellite TV

and wandering the infinite portals of the worldwide web

scavenging for that morsel of diversion that would sustain you

until you found the next one.

But Nick’s asset is also his curse; his talent isolates him from a language-impoverished world. Rather than spar with lackluster adults or scold Adam for his poor grammar, he finds a new niche for his talent: as a writer and performer of fiction. Creating Rachel, he says, is easier than he thought:

I figured out pretty quickly that

With every exchange,

Adam invented Rachel as much as I did. She’d say something totally generic…

Which led Adam to construct a whole matrix of assumptions about her.

Rachel, whom Nowak shrewdly keeps as sweet and wispy as a yearbook memory, is the internet in Dark Play. As conjured by Nick’s typing fingers, she’s a factory that repackages given information to bolster a fantasy. Nick, of course, is trying to realize his own fantasy, which is both to have Adam and to feel something deep, something denied him in real life. When he partly succeeds through means worthy of only the most odious frat boy, his awareness of his own monstrosity means he must also punish himself with physical pain. In director Logan Ellis’s hands, Nick’s pain, as tender and deliberate as making love, is very clearly the twin of his pleasure—or maybe even more pleasurable than it.

If the end of the play feels anticlimactic, like waking up from a bad dream—an older Nick, now hooking up with a girl, suddenly says, “I’m pretty much indistinguishable from any other college kid”—that might be because Nick’s punishment lobotomized him, making him no longer exceptional nor barbarous, the price of fitting in sexually and socially. It’s a crude ending, but one that suggests that we as a society don’t really know how to deal with killer nerds like Nick, people we push from live to online interactions. The killer nerds aren’t going away from our art, though; as we continue to wrestle with them, Ellis’s fine direction shows that the topic is well suited for the stage. Mercifully, he eschews electronics and simulations of electronics and miming of typing on electronics. His direction is bodies interacting in space, and nothing, as thespians know, is more alive than that.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here