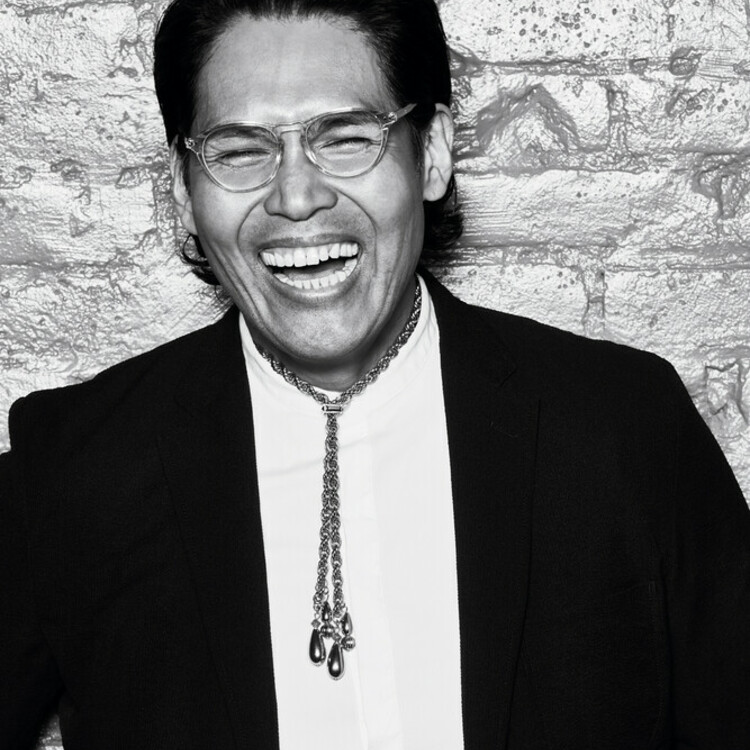

Clint Ramos is a designer, educator, activist, and creative producer. Lindsay Jones is a composer, designer, educator, performer, and advocate. Together, they have been friends and collaborators for many years, but each have also individually dedicated their efforts towards creating greater inclusivity and collaboration in the theatre community. They recently sat down together to discuss the intersection of being activists and artists, and their paths going forward to creating lasting and meaningful change for the next generation of theatremakers.

Lindsay Jones: Is there a specific moment you remember when you were like, “I can’t just be a passive observer anymore, I need to jump in and begin to change things”?

Clint Ramos: It didn’t happen like a quick turn, it was like an accumulation. I’m an immigrant. I went to grad school and it was mostly white folks. I saw these people were being invited to create the kind of work that was exciting to me and somehow I wasn’t. I experienced the usual immigrant shit where, before a meeting with the director, I’d arrive early and practice my English in front of a mirror. I couldn’t find a place in the theatre community. I couldn’t locate myself that way.

The biggest thing those experiences taught me is that I needed to take action. I needed to learn more and find some sort of family. That was the first real act of actively seeking a better world, to make sure I wasn’t imagining things. When you move here, you buy into things—like if you’re hardworking, you’ll get everything you want. It’s the land of opportunity. But I didn’t find that to be true.

When did you start thinking, “I gotta change this?”

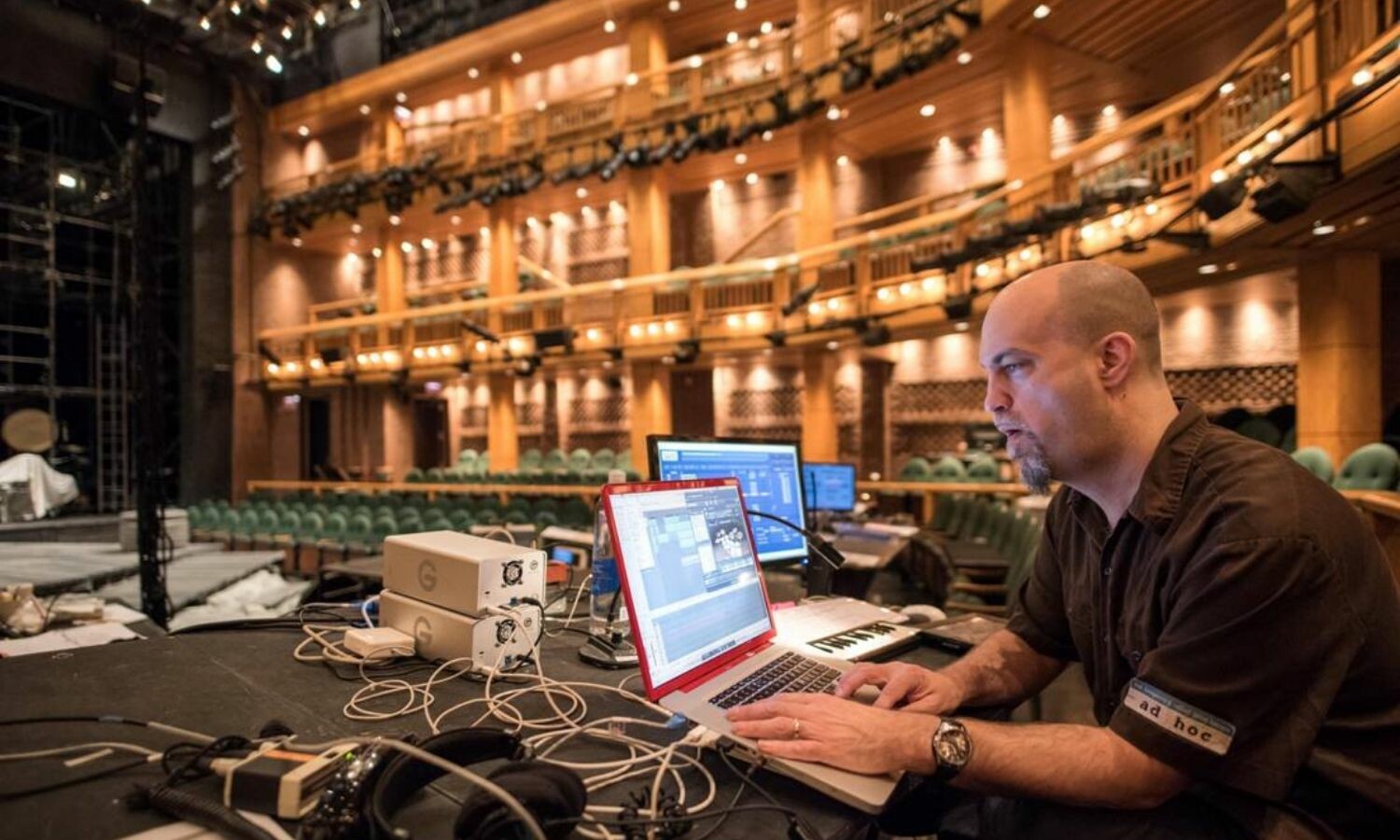

Lindsay: There were two moments that really affected me. When you work as a freelance designer, it’s a pretty isolated life. It’s just like the circus—you unpack your tent, do your act for the town, then pick up the stakes and go to the next town to do it again. That’s what my life was like for a long time. Then a friend of mine who was a designer, who I had worked with on several shows, was on his way to tech, walking from company housing to a ten out of twelve, and he literally dropped dead in the middle of the street. He had a heart attack and died. It really affected me.

Clint: I was in tech when that happened. I remember it being such a hard tech. I remember thinking he dropped dead because of what we do.

Lindsay: I thought, Wow, that could happen to me. But also it could happen to any of us. There are not that many of us in the world of stage design, and we all have similar concerns. If one of us goes down, that really affects all of us.

The other thing was when the Tony Awards eliminated the sound design categories in 2014. There was a lot of pain and confusion in the sound design community. I wanted to help channel that in a way that felt positive but also productive.

A lot of people at the time were like, “We should just make sure the Tony Awards don’t have good sound and then they’ll understand what sound design is,” and I was like, “That doesn’t help anybody and just makes everybody mad at us. What we really should do is figure out ways to explain to people what we do and show how we do it. Then hopefully they can figure out ways to appreciate it.”

From there, I began working on the Collaborator Party with John Gromada, which is an annual celebration of the entire theatre community. Then I worked with a bunch of other sound designers to help create Theatrical Sound Designers and Composers Association (TSDCA), which is an organization about community, education, and advocacy for sound designers and composers. Once you start on a path of trying to figure out how to make things more equitable, you find more and more ways to learn.

Clint: When I think about how the art I create is informed by activism… I can only work on something I could possibly be consumed by. It really needs to hit me on a deep level, like something that explores a solution to a social-justice dilemma.

Lindsay: What I really love about your design aesthetic is that everything you do is going to challenge the audience’s perceptions. You always seem to push it to another level—which, subliminally, forces the audience to confront internal biases and prejudices about whatever they expected.

I want to look for ways to accentuate or highlight the sort of sneaky underlying message of the play. I find your work endlessly inspiring for finding those messages.

Clint: One of the things I appreciate about working with you is that you get to the root of the idea quickly. You’re already in tune with what’s important. It also doesn’t feel like work, it feels very engaged.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here