Durational Theater Part 1

Time and Punishment

What is avant-garde theater today? It’s easy enough to look back on last year’s vanguard, but how can we define the movement we are in the midst of? In her series, Kate Kremer explores the question of the new avant-garde.

Tim Etchells is the co-founder and artistic director of Forced Entertainment, a British ensemble known for durational performances lasting from six to twenty-four hours. Yet in his article on Taiwanese-American artist Tehching Hsieh, Etchells is self-effacing: “six hours might seem quite silly when compared to Tehching’s yearlong pieces (laughable almost) but nonetheless, there’s something about duration, its energy and its inherent undertow of decay, that has always agitated and vitalised the space of performance for me.”

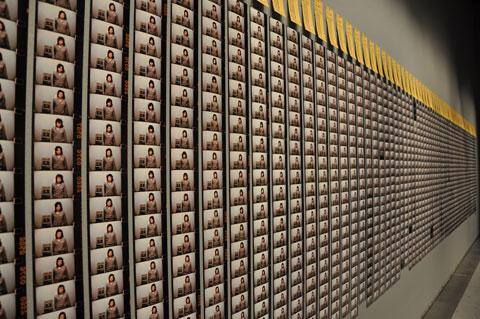

Tehching Hsieh became legendary for a series of yearlong performances created in the 1970s and ‘80s, during which he lived according to self-imposed “contracts” that placed him under rigorous constraints. From 1978-1979, Hsieh lived in solitary confinement. From 1980-1981, he punched a time clock every hour upon the hour.

From 1981 to 1982, Hsieh lived outside, not setting foot inside a “building, subway, train, car, airplane, ship, cave, or tent.” From 1983-1984, he lived attached by an eight-foot rope to artist Linda Montano—their proximity made more severe by the stipulation that they not touch. From 1985-1986, Hsieh lived without art. And then for thirteen years, Hsieh disappeared himself from the art world.

It makes sense that Etchells should feel an affinity for Hsieh’s work. Like Hsieh’s performances, Forced Entertainment’s “durationals” are improvised within sets of rules and constraints. Quizoola! involves performers continually asking and answering questions, competing among themselves for the audience’s laughter and attention; in Speak Bitterness, they perpetually confess. The durationals are, in Etchell’s words, “rule structures inside which the performers are free to operate, making real decisions about what they do next in reaction to what the others are doing, what the audience is doing, and what they feel like.”

Duration represents, for each, a way of making the work more felt. Hsieh has said that he tried to “make art stronger than life so people [could] feel it.” Indeed, his works stand as lived metaphors for varieties of imprisonment often unseen: incarceration, labor, homelessness, marriage, a life without art, a life lived invisibly. Through duration, the extraordinary constraints Hsieh imposes upon himself transcend the merely metaphorical. Art, endured for so long, is revealed as Life, and its “real” consequences must be recognized.

Likewise, Forced Entertainment uses duration as a means of sensitizing audiences to time and other people. Although the durationals have a new shape each time they are presented and do not cleave to any developmental arc, the physiological arc of six to twenty-four-hour performances is inescapable. The performers get tired. The audience witnesses their fatigue, and feels the increasing effort performance requires. As in Hsieh’s yearlongs, we come to see the life in the art. The durationals become portraits of people acting in time—and time acting on us.

Hsieh’s yearlongs and Forced Entertainment’s durationals are very different, however, in the way in which they engage their audiences. Discussing Hsieh’s work, Etchells underscores the importance of “story,” by which he refers to the art objects that document Hsieh’s lived experience: “Tehching’s work was witnessed first-hand by very few people. But as a narrative, and as a set of troubling and inspiring documents, it continues to circulate.” Only in retrospect, in the interplay between Hsieh’s contracts and evidentiary documents do we understand some part of what it must have been to live like that. In the absence of the artist and removed from the performance itself, to experience Hsieh’s work is to experience a series of gaps: between the art object and the artist’s experience; between our daily, assumed comfort and the pain we must believe the artist endured; and between the artist—who imposed on himself these limitations—and the myriad others who may live for a lifetime under such limitations without choice.

Whereas Hsieh’s audiences experience his work in his absence and through a fixed set of art objects, the performers in Forced Entertainment’s durationals are intimately present to their audiences. Etchells describes Forced Entertainment’s first durational performance, the twelve-hour 12 am: Awake and Looking Down (1993), as “a narrative kaleidoscope” in which silent performers repeatedly name and costume themselves with cardboard signs and second-hand clothing. In pairs, they present themselves to the audience in loose association but without interacting. The ensemble discovered that the piece was more powerful when the figures did not interact, because as soon as they did, the meaning crystallized and, in Etchells’ words, “the machinery stopped […] It’s much more interesting to let […] the story-making […] go on in the minds of the viewer.” In this way, Forced Entertainment’s audiences are involved not only in interpreting but, “more fundamentally, in making the work.” This quality is important to the group politically as well as aesthetically. It is a means of resisting commodification, of preventing the collapse of the work into a single experience, object, document, or interpretation.

There is also a tonal difference between the work of Hsieh and Forced Entertainment. Hsieh’s projects, so remarkable in their suffering and self-denial, are quietly heroic, almost Romantic in their emphasis on the life behind the work. They cannot help but inspire a sense of awe. Conversely, the dominant tone of Forced Entertainment’s durationals tends to be distinctly not heroic. Jonathan Kalb describes the group’s “self-conscious embrace of…hesitation, forgetting, ineptitude, [and] redundancy.” For Forced Entertainment, duration provides what Etchells describes as a “heightened sense of, ‘well here we all are then.’”

This tonal difference may have something to do with different concerns of theater and performance art. According to Kalb, the theater world “typically assumes that its artists must pay at least some attention to audiences” (if only to flout their expectations), the “visual art world […] sees ‘performance’ […] as an animate version of the inanimate work it displays on walls,” and feels “little obligation to adjust to audiences, or even acknowledge them.” This distinction, however, seems imprecise. Much of Marina Abramovic’s work, for instance, is devised with the audience explicitly in mind. From Rhythm 0 (1974) to The Artist is Present (2010), Abramovic’s work explores the autonomy of both audience and performer, along with the limits and possibilities of their relationship.

But it does seem that the durational performances of Hsieh and Abramovic differ from those of theater artists and ensembles such as Forced Entertainment, Nature Theater of Oklahoma, Mike Daisey, and The Hypocrites. Projects like Hsieh’s yearlongs and Abramovic’s The Artist is Present erode distinctions between life and art while pressuring and interrogating the question of what it is to be alive—can one be alive in isolation? In perpetual company? What conditions make life unlivable? And do those paradoxically heighten one’s sense of aliveness? Can one be alive without art? Can one be alive—or stay alive—if one surrenders autonomy, puts one’s life in an audience’s hands?

Conversely, duration in the work of such companies as Forced Entertainment serves to emphasize the live and unfolding quality of performance. How can we capture, in art, the feelings of failure, futility, and formlessness that are so much a part of our experience of living? How can we engage, through art, in a real, live search for meaning, which may or may not be there to be found? How can we feel more palpably our common aliveness?

***

Photo by Ruth White

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here