Every Body on the Dance Floor

On Jérôme Bel’s Ballet

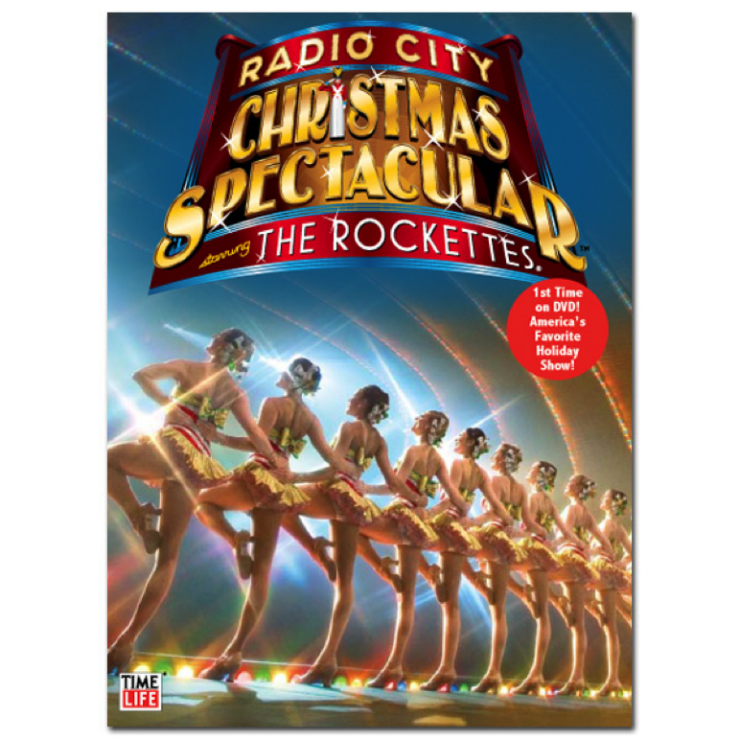

My body moved through the slow-walkers of Midtown. It was early November outside Radio City Music Hall, the seasonal debut of the Christmas Spectacular looming days away. On a peak holiday Saturday, the Rockettes perform six times, two separate casts of thirty-six dancers executing identical leg kicks from 9am to midnight. I glanced at the lobby doors and pictured the likely dress rehearsal inside, Rockettes adjusting each other’s sequins and ribbons, nursing blisters, offering notes of critique. How many rehearsals does it take for everyone to move in unison? If you standout as a Rockette, you’re not doing your job. Success depends on each dancer’s ability to assimilate into the whole, the collapse of identity into a single Rockette, not just in costume and eye shadow, but also in body, presence, and skill.

At the Marian Goodman Gallery a few blocks north, Jérôme Bel staged a counterpoint to such synthesis. According to Bel, “Any body can be represented. Any body can be interesting to watch.” His show Ballet consists of five instructions: Pirouette, Jeté, Waltz, Improv, Moonwalk. Twelve dancers of all heights, weights, dexterities, physical abilities, mental abilities, races, ages, and genders execute the moves as best they can. Bel’s radical body democracy gives every body equal stage time, isolating how each body carries out the move. Since its origins in the Italian Renaissance and the concert dance forms of France and Russia, ballet has been synonymous with grace. In Bel’s Ballet, grace is not the goal, but one of many possibilities.

Ballet is like watching a children’s recital, a community theatre show, a downtown dance piece, and a Lincoln Center ballet simultaneously. It’s like going to the karaoke bar with your mom, your little nephew, a Broadway musical understudy, strangers of varying vocal chops, and Celine Dion.

***

Chopin’s “Les Sylphides” sparkled from a speaker on the gallery floor, next to the word ballet, handwritten in Sharpie. Moriah Evans, a conceptual choreographer whose work had recently run at ISSUE Project Room, entered in a two-tone unitard. She delivered a better than average pirouette, then walked to the left side of the gallery. Hashiel Castro entered, much younger, in red pants, agile but not a dancer. He pirouetted. Charles Krezell, an independent filmmaker with white hair in a turquoise t-shirt slumped centerstage. Pirouette. Hector Castro, sporting long hair and black mesh. Adequate pirouette. Then Megan LeCrone, a ten-year veteran of the New York City Ballet (NYCB) pirouetted effortlessly in traditional slippers and white tutu, elegance personified. But the audience responded in a way she may have never encountered onstage before: laughter. In the context of an NYCB performance at Lincoln Center, the audience expects her virtuosity. Grace is what they’ve paid for. In Ballet, after four middle-of-the-road pirouettes, being good is surprising. Being good is a punchline.

The opposite of the ballet body might be the comic body. In the book Concrete Comedy, David Robbins writes, “The comic body fails. The comic body stumbles. Comic legs have a tendency to run the body into closed doors. Comic hands tend to drop the priceless vase.” Bel makes the expert seem overwrought, the slapstick seem poignant. As an audience member, I rooted for the unpracticed, comic bodies. When Frog, a lanky man in a camo tank top spun and almost fell over, I didn’t laugh, I empathized. When Anne Gridley, an actress who often performed with Nature Theater of Oklahoma, leaped, performing her version of a jeté, she looked intensely at the audience. Her jeté wasn’t “good,” she barely made it off the ground, but she used the awareness of her “badness” to her advantage. Unlike Frog, Gridley is a veteran performer virtuosic at playing her amateurism for laughs. During her moonwalk, she tried to toss her wristband into the audience, and it fell two feet in front of her. Think of Mikhail Baryshnikov and Kristen Wiig illustrating the same move. Technically, both are expert performers, but with almost diametrically opposed skill sets. Ballet creates opportunities for its performers to showcase alternate virtuosities. LeCrone may have “won” the pirouette round, but she looked uncomfortable moonwalking. Moriah Evans’s ballet and waltz moves were pedestrian, but her moonwalk garnered the night’s biggest applause as she virtuosically slid and slithered to “Beat It.”

***

Etienne Servaes, a little boy in a yellow “Dominate Everything” t-shirt pirouetted. Alex Clayton, a modern dancer, who at 5’4” would often be considered too short for ballet, pirouetted beautifully. Madison Ferris rode her mobility scooter in a circle, pirouetting. Casey Furry, a mentally challenged woman in a pink skirt and black leggings, pirouetted.

Bel’s 2012 piece, Disabled Theater, received criticism for its alleged exploitation of its mentally challenged cast, accusations that the piece tipped more towards sideshow act than aesthetic critique. In some ways, Ballet is a revision of Disabled Theater. Whereas that show’s cast was an isolated group, Ballet stresses inclusion of all skill levels and backgrounds by gathering, as Bel told me, “as many relations to dance as possible” on one stage. Equal time and value given to the pro and “the middle, the average, the non-special.” Ballet is like watching Disabled Theater, a children’s recital, a community theatre show, a downtown dance piece, and a Lincoln Center ballet simultaneously. It’s like going to the karaoke bar with your mom, your little nephew, a Broadway musical understudy, strangers of varying vocal chops, and Celine Dion.

And because the cast consists of amateurs with day jobs, the performers can’t tour. Bel re-casts the show in each city, which doubles as a method for maximizing the show’s liveness. Too much rehearsal would strip the performers of agency, settling them into patterns and staid gags, lessening their ability to genuinely react. If the performers toured, Frog would become more like Anne Gridley, more comfortable, and the show would miss its mark. I saw the second performance, and Bel said he and the performers had only practiced twice before opening night. “You rehearse and rehearse to get control, but the more I work, the less I want control.” The mentally challenged cast of Disabled Theater “did whatever they wanted and it was marvelous. It was pure theatre. Now, with all different types of people, I try to experience and not judge. I don’t modify anything.”

As the performers bowed, I looked around the Marian Goodman Gallery. If this piece was about democratizing the representation of bodies, which bodies were watching? Did the audience consist of people from diverse backgrounds or art professionals cheering on amateurs? Is the goal to demolish the fourth wall and put a mirror in its place or for Bel and myself and a privileged audience to democratize our own viewing and casting practices? What if we left one Rockette onstage and called thousands of tourists and slow-walking shoppers onstage to join her, all kicking their hearts out at Radio City?

In a talk Bel delivered at the Performa Hub, he said that the first level of appreciating art is identification, an aspect that falls away when “all the dancers are able-bodied and twenty-two to thirty-five years old.” When watching Ballet, the body most like mine was Shelton Lindsay, stage name Professor Cupcake, a white, hairy, skinny man spinning shirtless in high-tops and multi-color tights. Every once in awhile he achieved a silly form of grace, but most often not.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here