In São Paulo, as President Jair Bolsonaro’s administration comes to its end after four years of continuous attacks on the arts, Brazilian theatre workers have reasons to be hopeful again. Not only are they celebrating the fact that new President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva recreated the Ministry of Culture and will reestablish funding programs for the arts, but they also feel that it makes sense, in civilizational terms, to produce plays once more after the fall of the man who has been the closest thing to a fascist leader that Brazil has ever had. Bolsonaro’s tenure has been devastating for the Brazilian theatre, which is mostly an activity carried out by autonomous groups with no chances of commercial success and financial subsistence. Theatre needs governmental support in Brazil, and the former president has done everything he could to curtail it.

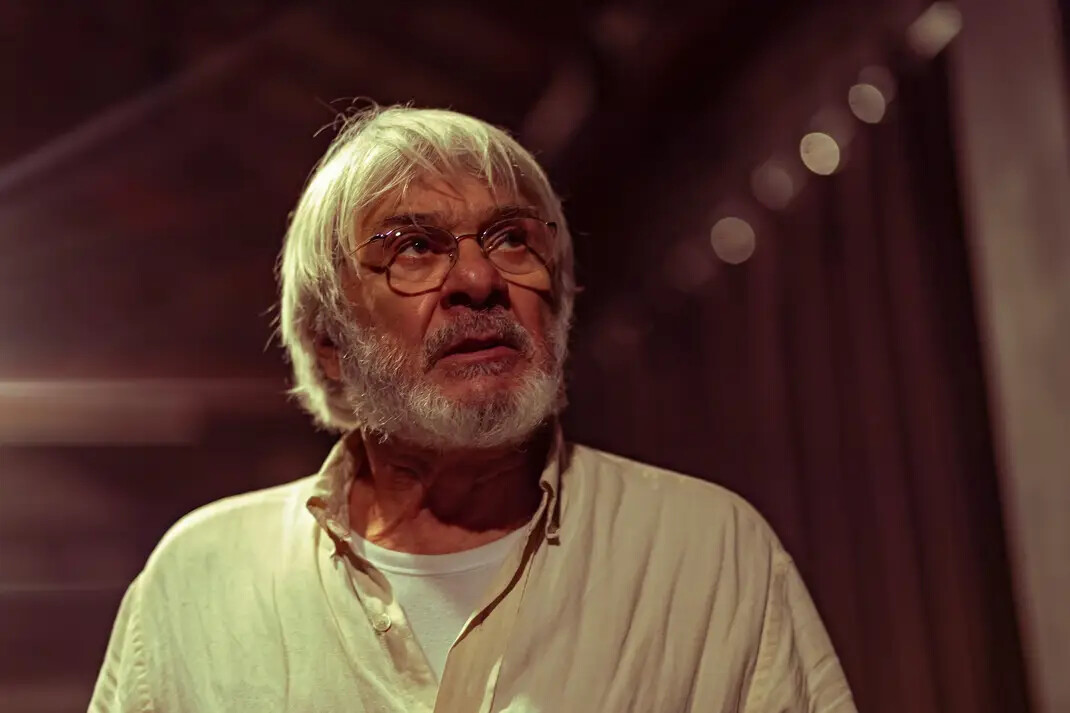

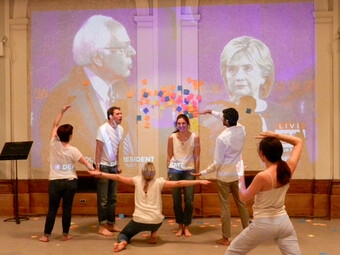

Nevertheless, many groups resisted and kept working and suggesting a critical view on the South American country’s politics, society, and history. One of the most meaningful plays presented this year in Brazil, Papa Highirte, is a piece written by Oduvaldo Vianna Filho (known as Vianinha) later in 1968 and tells the story of a Latin American caudillo (a military or political leader) who has many connections with Bolsonaro’s political nature. Staged by Grupo Tapa, a decades-old theatre company notorious in Brazil for its superb acting and fidelity to play scripts, the play’s full significance was seen on 30 October 2022, when Lula defeated Bolsonaro in a fierce run-off election. After two runs of Papa Highirte—the first one between May and July and the second one between August and October—Grupo Tapa is planning a new season now.

Papa Highirte was the most Latin American of the pieces written by Vianinha (1936-1974), whose work distinguished itself because of its profound dissection of the Brazilian problems. The son of a communist couple of playwrights, Oduvaldo Vianna and Deocélia Vianna, Vianinha was very young when he founded a students’ theatre group in 1955, which merged one year later with Teatro de Arena, a major modernist stage in São Paulo. Teatro de Arena was the first theatrical company in the country to stage the problems of the working masses. Eles Não Usam Black-Tie (They Don’t Wear Black Tie), written by his longtime colleague Gianfrancesco Guarnieri in 1958, marked the first depiction of the organization of a strike in theatre.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here