Hakawatis and the Role of Artists in Uniting People

I was born in Beirut, Lebanon in 1991, only a year after the end of the fifteen-year civil war, which makes me part of the post-war generation faced with the consequences of the devastating conflict. My father—a mime artist, educator, and writer-director—constantly reassured me throughout my childhood not to worry, that artists hold the strongest weapon of all: their pen. The pen, of course, representing their independent thoughts, the power of their words, and the artist’s responsibility to hold a mirror up to society.

Like the passing of a baton, I inherited the role of storyteller from my father, who had himself gotten it from his uncle—one of the last known Hakawatis of the northern Lebanese city of Tripoli. In Arabic, Hakawati means “storyteller” and refers to the ancient Middle Eastern profession, which is rarely performed in the traditional sense. This oral tradition consisted of the Hakawati gathering crowds of people in the town square or local cafes and telling the tales of epic characters from myths, legends, and Quranic fables, or of heroes the Hakawati allegedly came across on their travels. The oral Hakawati tradition could help listeners escape their daily woes, taking them on a rollercoaster of emotions that would end with a morality lesson, but leaving them with the perfect cliffhanger guaranteed to bring their eager ears back to the square again for the next saga.

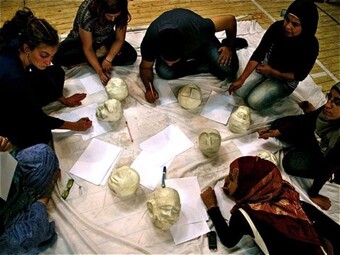

To keep their audience engaged, some storytellers would carry rods to emulate daring sword fights, and they would occasionally integrate their friends with pushcarts or businesses into the narratives—a classic modern-day plug. Although my father and I are not traditional Hakawati storytellers by profession, I see my great uncle’s values at the center of our work as artists. As if pursuing an ancient civic duty, our role is still to unite people—whether in art galleries, concert halls, or theatres—and aid in cultivating a space for expression, empathy, and conversation, which can strengthen the bonds of a community and make way for social change.

A familiar panic had set in: Who was telling this story? Was it in safe hands?

Amplifying the Voices of the Egyptian Activists

When brothers Daniel and Patrick Lazour wrote We Live in Cairo, they were determined to amplify the singular voices of the Egyptian activists and immortalize this historical triumph. The musical originally ended with what is now known as the celebratory act one finale, when the revolutionaries succeed in overthrowing their president of thirty years, Hosni Moubarak. The story unfolded to include the aftermath of the revolution—which now comprises act two—offering a closer look at what divided or stifled protests and honoring the realities of activists still suffering under government crackdowns today. By making a conscious decision not to breeze past these authentic stories, the brothers challenged the form of the musical by not giving in to an expected structure or resolve, thus capturing the grim realities of a feat that cannot end in two and a half hours or even a decade.

The characters were presented with their own complexities, which broadened the typical dimensions of Arab characters and stories in drama. They questioned their faith and leaders, fell victim to their country’s brain drain, did not have the right to civil marriage, were queer in different social classes, and more. No matter the reason, these revolutionaries used whatever was at their disposal—cellphones, computers, cameras, spray cans, and the most powerful platform behind the revolution: social media—to mobilize and organize protests as well as raise awareness about the events in Egypt to the world. Every night, the show conjured up historical figures like the martyr Khalid Said, whose unjust death was a catalyst in the revolution. And, every night, the audience participated in a moment of silence led by the characters on stage in his memory. Bringing his tragic and unjust end into every audience member’s conscience was activism at work. We all paid our respects: cast, crew, and audience.

On 18 May, during the run of the show, Said’s mother passed away, and Egyptian authorities canceled her memorial service from fear it would instigate another uprising. On 17 June, while the show was still running, former president Mohamad Morsi, who was serving a life sentence, collapsed in a court hearing and later died of a heart attack. Something was brewing again, and the show felt indirectly engaged with it. The set—covered with projections of real social media posts, which were the driving force behind the movement and were used for the dissemination of truthful reports and to combat misinformation propagated by biased media—heightened that feeling. Contrasting the modern aesthetics of social media interfaces was a graffiti wall scrawled with slogans of the revolution and a lounge full of pillows, instruments, and shisha, which organically captured the communal and intimate nature of Arab gatherings, where it’s near impossible to walk away without a heated political debate.

The characters were presented with their own complexities, which broadened the typical dimensions of Arab characters and stories in drama.

Representation in Storytelling

Almost on a daily basis for the whole run, I walked to the theatre simply to stare at our poster in joy and disbelief. One day during previews, Taibi asked me to translate and record the pre-show announcement in Arabic. I didn’t think much of it other than that it would be an exciting addition to the whole experience of the show. But the first day the welcome speech played, I received a notification on my phone from Dana Omar, who played the role of Fadwa. It was a video of her, sitting still, with eyes full of tears as the announcement played through the dressing room speakers. I would have never guessed the Arabic announcement would have such an emotional impact on anyone. Having lived my whole life in Lebanon, I had taken for granted what my Arab-American friend was painfully missing: hearing her own native tongue at her place of work, in the country she’s lived her whole life in. It began to set in that We Live in Cairo was more than your typical musical, and having it produced at such a scale was a milestone for our community and a promise that there is a place for us.

Since starting to write this article, worldwide protests led by the people of Egypt, Lebanon, and other countries began to spread in another uprising and serendipitous twist. Suddenly, the potential power of We Live in Cairo went from immortalizing the voices of the revolutionaries to helping reignite another wave of the revolution. As a response to these developments, Mark Lunsford, A.R.T’s artistic producer, decided to program a series of music and storytelling events to bring these injustices to light at the theatre’s OBERON space (which took place on 28 October 2019) as well as at Joe’s Pub in New York City (on 9 December 2019).

At the Boston event, Egyptian expatriates read the testimonials of prison nightmares and brokenhearted love letters sourced from Egyptian activists, some who remain behind bars or in exile. This was to honor the voices of the three thousand Egyptians arrested in the last week of September—not to mention the other victims of the government crackdown during the revolution and in the last decade. I took the stage again and spoke of the Lebanese revolution, which was sparked on 17 October 2019 and is ongoing. I shared about the queer community and LGBTQ+ activists who have been fighting for the basic right to exist long before this revolution.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here