I Wrote a Play with a Male Rape, But Readers Didn’t Want to Call it That

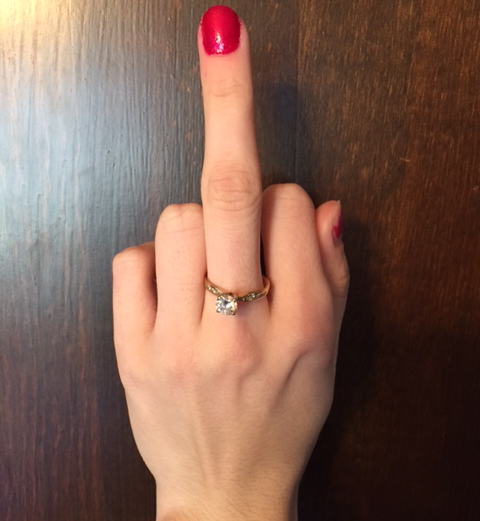

My play The Way It Is features Cane and Yasmine, a couple who have broken up. When Cane returns to the apartment they shared to retrieve his mother’s engagement ring, he is raped by his ex. At least it is my intention that he is.

When I first wrote the play, I showed it to two trusted readers; both said it was the best thing I ever wrote. So I sent it to some more friends, and while they liked the immediacy and the writing, they described Yasmine as crazy, which seemed to mean, to me at least, that the play was unworkable, which, of course, was bothersome. The other bothersome thing is that nobody—beyond those first two readers—seemed to see the final scene as rape. There were euphemisms like “gun sex” (there is a gun involved), but the word rape didn’t come up at all.

How could that be? More importantly, how could I fix it? How could I make people see that ending differently? After much internal debate, I changed the play to add a second ending. In this version, Cane leaves and the audience sits in darkness for twenty seconds contemplating what they’ve just seen. Then, Cane comes back and the final scene plays in reverse with nearly the same dialogue. Being forced to compare both scenarios would make audience members rethink what they’d seen prior, and perhaps view it through a different lens. And from a play perspective, perhaps audiences would wonder which was actually the real ending, which might be cool.

I sent the play out to some more people to read. Amazingly, nobody called Yasmine crazy anymore. Nobody. Not a word of her dialogue had changed, but she was no longer crazy. That was good, right? Except that two very respected readers both said that the second ending was unnecessary, that the first ending was very clear and organic, and the second felt tacked on. Aaargh! Would they have felt that way without having read the second ending?

Because that’s what I’d felt at the start, I took their advice, went through the play, revised to elevate Yasmine’s sympathy quotient, and happily removed the second ending. Shortly after, another friend read it and said Yasmine was crazy. Then a director read it and said she was crazy—and called the ending “gun sex.” I wanted to tear my hair out.

Yet the fact that only three readers out of nineteen used the word “rape” is telling, confounding, and illustrative of different perceptions on this issue. Maybe what rape is to me truly isn’t to someone else.

I wrote back to this director and explained my process with the endings thus far, particularly highlighting the “crazy” feedback. He wondered if calling Yasmine crazy ran along gender lines. Since all but one of the previous readers had been men, I didn’t know. Thus, my idea for an experiment: I asked for volunteers on the Official Playwrights of Facebook to help with this experiment. Nineteen playwrights raised their hands (I need to sidebar here to offer them a mighty thank you; this wonderful dramaturgical tool was possible only through their generosity). I sent my play without the second ending to all of them, who read it immediately. When they were finished, I asked them three questions:

- Give me three words to describe Yasmine.

- Give me three words to describe Cane.

- In a sentence, describe what happens at the end.

My goal: to see how many “crazy” descriptions I got for Yasmine, and from whom. The third question was for me to see how people perceived the initial ending independent of the second. (For fun, I asked them to optionally tell me if they’d want to see the play, and why or why not.) The results were fascinating:

- People do not like to use the word rape, as evidenced by the way the respondents went out of their way to avoid it. Whether this is because they don’t recognize rape when they see it, or because they’re uncomfortable labeling it, I don’t know. Both situations are uncomfortable for me because if we don’t recognize it and name it, how do we ever have conversations that can change rape culture? Only three readers identified it as rape, and one added that writing the words “Cane gets raped” was difficult and he second-guessed himself. That made me wonder how much this happens in real life; do we tend to reframe uncomfortable incidents after the fact? In that split second after reading, did other readers abandon “rape” and instead call it a death dance; intense and troubling; a plan that worked; Yasmine getting what she wanted; a classic good-bye fuck; or powerful break-up sex? One reader did say Cane was forced, but “accidentally” got into it. Another simply described the scene clinically. Although most said they would want to see the play, one said no because the situation was “too familiar.”

- Too familiar? That either means my sex life needs some serious ramping up, or the definitions of rape, what is consensual, and what is “fun” are so blurred that it’s no wonder we have problems talking about rape culture, let alone getting anybody to agree. I have no doubt that if this situation were reversed—if readers read/saw the second ending—they would view the first ending differently. Yet the fact that only three readers out of nineteen used the word “rape” is telling, confounding, and illustrative of different perceptions on this issue. Maybe what rape is to me truly isn’t to someone else. We all have our own realities, but somewhere there is—there has to be—a line. These are conversations we need to have.

- If you had any doubt that plays are colored by the perceptions and experiences of audience members, the diversity of adjectives used to describe these two characters is proof positive. Though “manipulative” and “desperate” led the pack for Yasmine, she ranged from sensual, mercurial, sexy and selfish, to hurt, and smart. Surprisingly, only two people described her as “crazy”—both women. Cane was also selfish, as well as thoughtful, weak, proud, purposeful, childish, smug, and indecisive, among other descriptors. It was fascinating to see that no matter how we view our characters or the situations we put them in, they will be other things—sometimes completely opposite things—when viewed through different lenses. The good news: with this play, that’s the whole point.

- I absolutely don’t need the second ending. Depending on the responses, I was going to have a Phase II where I had a different set of readers read the play with the second ending to see how/if these answers changed. But I didn’t need to and I’m glad for that. I don’t want two rapes on stage back-to-back, and as there would likely be no doubt the second instance was rape—it would be gratuitous. But more importantly, it doesn’t matter that I—or audience members—view the ending as rape. What matters is that the varied perceptions of it are explored. Bad idea smacked down and best result ever—dramaturgical gold.

On the other hand, I’m giving all the readers the benefit of the doubt and thinking—hoping—that if they watched the play, or even heard it at a reading, they would feel uneasy and want to explore why. And then I hope that following this mythical production, those who disagree or are confused over what happened go out with friends after and hash it out over drinks. And that the idea that it might have been rape comes up, and surprises someone. And maybe convinces another. And the conversation continues.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here

I think the telling thing here is that many people are invested in the idea that men cannot be raped. The standard societal narrative is that men are up for sex always, sex is a good way of proving your masculinity, and if you do not want sex with an attractive woman there is something wrong with you and you are less of a man because of it.

So if a man is not interested in sex for whatever reason and is raped, that creates a Does Not Compute error in many people's minds, because there's no room for that reality in the larger narrative.

The fact is anyone of any gender can be raped by anyone of any other gender; yes, even if you experience arousal, yes, even if you experience orgasm. Male rapes are horrifically underreported, and I think your experience with this play illustrates why that is.

I couldn't agree more.

Please don't overlook that the rape of women is also horrifically under-reported.

I have a different play to deal with that issue.

In some (edited) courts of law, male rape does not exist. Rape is the exclusive experience of women, and in my opinion should not be weakened by suggesting that men--who cannot be impregnated--can experience rape. When a man is anally penetrated against his will, the crime is sodomy. When a man is sexually assaulted or battered, the crime is sexual assault/sexual battery. Please consider using the proper language, such as non-consensual sex, to describe what happens to the character in your play and avoid a misuse or variant application of the word "rape". The stakes are much higher for women in cases of sexual battery and rape, and our language should reflect that lest we diminish the trauma of a woman's rape.

The definition of rape IS non-consensual sex. Sodomy is anal sex, consensual as well. "Rape is a type of sexual assault usually involving sexual intercourse or other forms of sexual penetration perpetrated against a person without that person's consent."

Not sure what happened to your other reply, but it wasn't clear you were referring to criminal definitions only. But if criminal definitions haven't yet caught up with dictionary definitions (which you say are ahead), doesn't that point to a need to have them catch up rather than accept that men cannot be raped?

Donna, I'm sorry I've come to this essay so late. Thanks for writing it.

In terms of whether or not readers consider what happens in the (original) final scene of The Way It Is to be rape, I wonder if we're not overlooking one factor so obvious that it's easy to miss.

You haven't mentioned this in your description of the scene, so let me ask it. What sort of sex, exactly, does Yasmine coerce Cane into having with her? Does she peg him with a strap-on? Or is it standard penis-into-vagina sex?

Given that so many of your readers characterized it as "gun sex" or "powerful break-up sex" and that one said that Cane "'accidentally' gets into it, I'm guessing it's standard penis-into-vagina sex (referred to hereinafter as SPIVS).

While it's unfortunately true that some women who are raped are betrayed by their bodies and exhibit physical signs of arousal, male-on-female rape can and does happen all the time with zero arousal on the female victim's part.

On the other hand, SPIVS pretty much can't happen without physical arousal on the part of the male, even if he's coerced by the female.

That being the case, I think many people - rightly or wrongly - can't really conceive of SPIVS as being rape of the male, even if he's being coerced at gunpoint. If he's erect, the thinking goes, then he's physically aroused, and therefore he cannot be an entirely unwilling victim.

And I think there's another group of people who can conceive of what Yasmine does to Cane as rape, but - given the reality of women being raped without any physical signs of arousal, and given the power differential between men and women generally - who would be hesitant to use the word rape out loud in any case of SPIVS, however coerced.

Does this make sense? Does it help explain the reactions you've gotten from readers?

It makes sense, but it doesn't make it less true, and is likely the reason male rapes go largely unreported.

Oh, of course it doesn't make it less true. And yes, I agree that it's the (or at least a) reason why male rapes go unreported. (Elana gave other good reasons.).

But In your essay, you seemed not to understand why some people could see/read what Yasmine did to Cane and not characterize it as rape. So I was taking a stab at explaining why. But I certainly don't agree with that reasoning.

Anyway, Donna, thanks for responding.

I may have slightly misunderstood your comment (especially reading it after the other one), but what I wanted to convey was that a) I came to a realization why people misunderstood and b) that that realization demonstrated an even greater need for these conversations. But I am in total agreement with your assessment.

My father is a psychologist who specializes in men who were sexually abused or raped as boys. One in four men have had this experience but rarely talk about it. The issues that come up when a boy or a man is raped are sometimes similar and sometimes different from those of a girl or woman's experience. There are issues around machismo, particularly if the perpetrator is a woman. There are issues around being gay, whether they are, if the perpetrator is a man. The list goes on and on. It does not at all surprise me that people don't recognize a situation as rape, don't want to talk about it or think that your female perpetrator is "crazy". But I'm very glad that you did your homework with the playwrights on Facebook and got more opinions to see how it was reading to people. My guess is gender lines are related. How could they not be? If you need any clinical information on this stuff, let me know. I'm happy to help. It's an issue that should be on stage. (with one ending)

Thanks, Elana. Actually, it was two men and one woman who called it rape. --Donna

I think you care too much about "what other people think." You can't write to committee. I don't think you'll find your writers voice that way.

On the contrary: I care that my play is doing what I want it to and now I am convinced that it is. I wasn't looking for advice, just answers.

Look at « American crimes» on ABC! Wort it. To feel les alone. :)

I have subsequently heard they are addressing this, which is great!

So far--unless something has changed in this week's episode, which I haven't watched--American Crime is covering male-on-male rape, which is a very different beast.

Oh yes absolutely! Thank you for the clarification!!