Priya Parker, author of The Art of Gathering: How We Meet and Why It Matters, has an answer to that first question:

We gather to solve problems we can’t solve on our own. We gather to celebrate, to mourn, and to mark transitions. We gather to make decisions. We gather because we need one another. We gather to show strength. We gather to honor and acknowledge. We gather to build companies and schools and neighborhoods. We gather to welcome, and we gather to say goodbye.

And yet, she points out, with “so many good reasons” for getting together, we often “don’t know precisely why we are doing so.”

In theatre we, too, have “so many good reasons” and usually so little precision of purpose. We share space to share stories or ideas or ways of being together. We seek to educate and entertain. We put on plays to promote empathy, to be more cognizant of others—those we love and those we’ve never met. We heighten our awareness of human distinction and human connection. We grapple with conflict and uncertainty; we grapple, in tragic form, with the inexorable.

But these are what Parker calls categories for gathering, not “vivid” purposes. How, for example, do we define the “space” we wish to share? Even within the profession, our uneasy terminology reveals a lack of clarity: Are we creating “sacred” space, “safe” space, “brave” space, “healing” space, “play” or “imaginative” space? What if my bravery triggers your trauma? If we bring audiences into a “shared” or “communal” space, what have we done to make it so?

And who is here among us? Who was left off the invite list? Will our sitting together confirm our similarity or help us overleap difference? What do we really want: Confirmation or challenge?

I ask these questions in a time of absence, which has made my heart grow fonder of the theatre I miss. I ask these questions as a white male, older than I like to acknowledge, who has held several leadership positions in the field. And I ask them in times that keep changing: before pandemic, during lockdown, immediately after the killing of George Floyd, in the days of uprising that become powerful weeks.

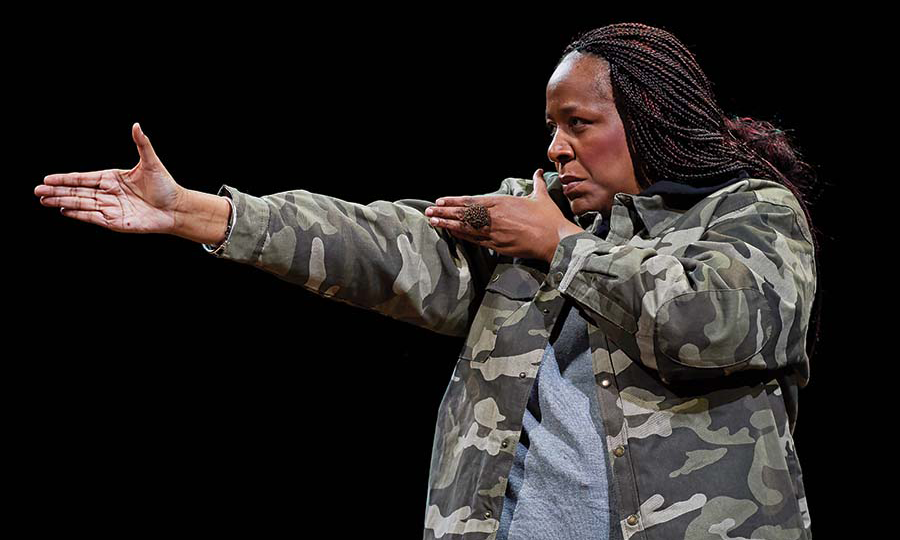

As I write, the streets of the cities in which we have built so many of our theatres are filled with protestors. In these cities, where we have built repertoires of mostly Western European dramas and their American offspring, secure in the knowledge that this canon revealed our “common humanity,” Black and brown people continue to be beaten, corralled, and killed. Artist-leaders of color, with more frequency and urgency, call out the lies—the under-lies—of our institutions and practices, the many ways “common humanity” is just another term for “dominant culture.” In her address to the Theatre Communications Group virtual conference in early June, actress and writer Nikkole Salter labeled this “epically injurious” time an “opportune time” as well. Might this moment of “breakdown,” she asked, also be one of “breakthrough”? What if this interregnum offers our best chance to take stock and, being so radically undone, redo what we’ve done so wrong? How might we sit together?

The mainstream, predominantly white American theatre, both nonprofit and commercial, has skipped half the equation. So good at making plays, it has failed at gathering.

A Moment to Just Be with Each Other

Sometimes it doesn’t help to sit together. Sometimes somebody needs space apart. “Thoughtful, considered exclusion is vital to any gathering,” says Parker “because over-inclusion is a symptom of deeper problems—above all, a confusion about why you are gathering and a lack of commitment to your purpose and your guests.” The idea of exclusion runs counter to deep-held liberal theatre principles, but even our most high-minded theatres have been excluding a lot of people for a long time—by means of ticket price, season offerings, architectural design, location, marketing—and lying to themselves about it. As someone who has almost never felt unsafe or unwelcome in a theatre, I don’t have to work hard to conjure up the people who would probably feel unsafe and/or unwelcome in any one of the thousands I’ve visited.

In today’s theatre (or yesterday’s theatre, right before the global hold button froze everything mid-stride) the need for a space apart is especially true for artists of color, who, in the United States, have seen themselves portrayed through the eyes of a dominant culture since before minstrelsy. In the nonprofit professional theatre, this call for a space apart dates at least from 1926, when W.E.B. Dubois imagined a Black “folk” theatre “about us, by us, for us, near us.” Forty years later playwright/director Douglas Turner Ward published the New York Times essay “For Whites Only?” that led to creation of the seminal Negro Ensemble Company. Ward wrote that, for Black playwrights, “the screaming need is for a sufficient audience of other Negroes, better informed through commonly shared experience to readily understand, debate, confirm or reject the truth or falsity of [the playwright’s] creative explorations.”

While Ward sought a mostly Black audience, playwrights like Jackie Sibblies Drury and Aleshea Harris answer his “screaming need” from inside their plays, charting a new canon by creating intentionally separate spaces—or what Ibram X. Kendi refers to as anti-racist spaces. “Separation is not always segregation,” Kendi writes in his memoir/treatise How to Be an Anti-Racist. Sometimes, for example, when Black people “voluntarily gather among themselves,” separation is an attempt “to separate, not from Whites but from White racism.” As Parker puts it, “Let purpose be your bouncer.”

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here