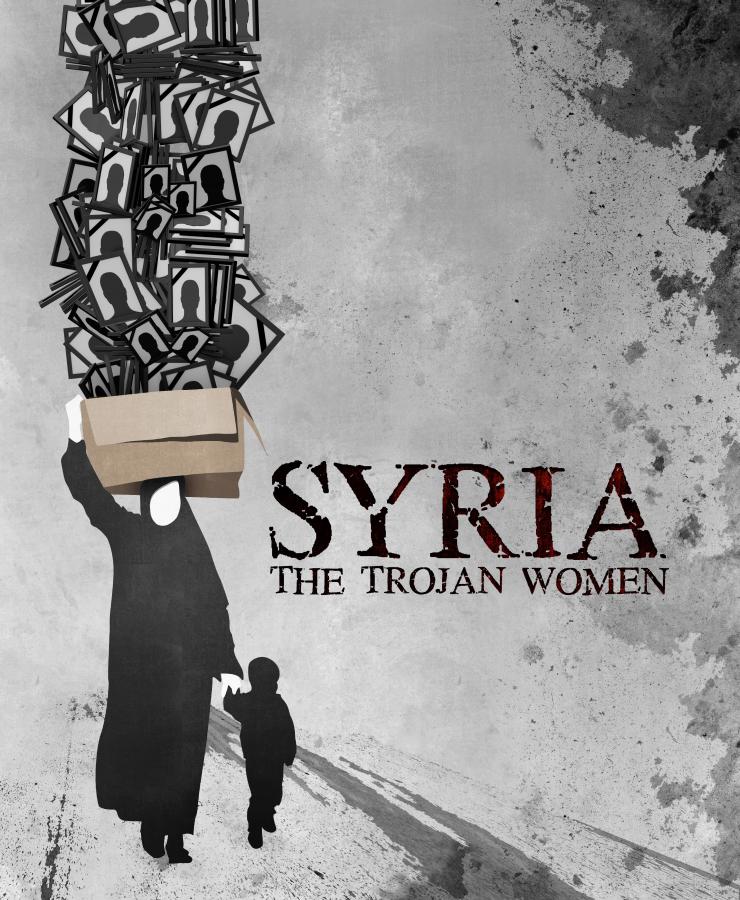

Listening for Unheard Voices—Syria

The Trojan Women

I have a scream I want the whole world to hear, but I wonder if it will be heard.

—Suaad, cast member of Syria: The Trojan Women

Re-interpreted by a group of women forced to flee their homes in Syria who now live as refugees in Amman, Syria: The Trojan Women weaves the individual experiences of these women in a 21st-century conflict into Euripides’ 2,500 year-old text.

After premiering in December 2013 in Amman, Jordan to international acclaim, the Laboratory for Global Performance and Politics at Georgetown University, founded by Ambassador Cynthia Schneider from the School of Foreign Service and myself, has planned to host these remarkable women this week in their first North American performances as part of a two-week residency to launch Myriad Voices: A Cross-Cultural Performance Festival, a two-year project that is part of the Building Bridges Campus Community Engagement Program—Expanding Awareness and Understanding about Muslim Societies through the Performing Arts, from the Doris Duke Foundation and the Association of Performing Arts Presenters (APAP).

The project speaks deeply to us both because of its extraordinary artistic merit and because we feel that the voices of these women, and by extension the voices of over two million Syrian Refugees, are almost entirely unknown and unheard by US audiences. The women of Syria have experienced the destruction of their homes, have had family members, brutalized, raped and killed, and have been forced to flee into exile, losing their community and their status as citizens. The production of Syria: The Trojan Women artfully weaves the poignant and harrowing testimonial narratives of the women—none of whom have previous theatre experience—as well as letters of their own creation to loved ones still in Syria and scattered in exile, against the backdrop of tableaux, scenes and choral episodes from Euripides’ ancient play.

The Trojan Women premiered in 415 BC as an enraged anti-war protest against the brutality inflicted by Athenians when they took the island of Melos, slaughtering the men and selling the women and children into slavery. Conceived by London-based Refuge Productions, Syria: The Trojan Women grew out of workshops in Amman led by director Omar Abu Saada in which more than fifty Syrian refugee women participated (and more than 100 others had to be turned away).

***

My name is Farah and I am twenty-years-old. The line I most like in the play is "My tears had escaped, who would give eyes to cry with.” I love this line because I am in a lot of pain, but I don’t show anything to the world. I cry a lot to the point where I don’t have any more tears. I wish someone would give me an eye to cry with. —Farah, Syria: the Trojan Women

We learned in the past couple of weeks that despite many months of constant efforts and extraordinary advocacy on the women's behalf from a wide range of top officials, ambassadors, and legal experts, the US Bureau of Consular Affairs in Amman denied the visa applications of the women performers, under section 214b of the Immigrant and Nationality Act, failure to demonstrate non-immigrant intent (despite the women's deep ties to their children and young families in Amman).

Determined to do what we can to share their stories and to lift their unheard voices, this Friday, September 19th at 7:30pm EDT at Georgetown, we will host and livestream Voices Unheard—The Syria: Trojan Women Summit. This one-time event will include recorded excerpts and behind-the-scenes documentary footage from the process; live discussion with the women (via live-stream from Amman) and with the project’s celebrated Syrian director Omar Abu Saada; and discussion with a range of leading policy experts and artists about the political realities in the region and the role of art as a humanizing force.

More than ever, this is the time for Syrians to show their beautiful unforgettable aspects: The Women, the Art, Nonviolent work. Civil society building.

We have been deeply moved by the outpouring of support for these women and this project from around the world, thanks in large part to important coverage from Peter Marks in The Washington Post and Scott Simon on NPR’s Weekend Edition. The words of Hind Kabawat from the United States Institute of Peace, who has been on the ground in Syria and will be one of the voices participating in the summit, eloquently reflect the sentiments we have been hearing from many:

Yes, it is the reality happening in America: a group of Syrian refugee women have just been denied visas by the United States government. They were to come here to perform their art.

After all the violence and adversity which these women have faced and overcome, the US State Department rejects them. As an activist for Syrian refugees and for civil society work among Syrians, I feel devastated by this decision. More than ever, this is the time for Syrians to show their beautiful unforgettable aspects: The Women, the Art, Nonviolent work. Civil society building.

I have learned from my American education that one must "lead by example." When a country claims to advocate for freedom of women, and for civil society, then denies refugee women the chance to come to the US to show their hard-won art and to express themselves in their own voices, this is not leadership "by example." I am very upset.

It is also true that, as Peter Marks has observed, the press coverage of the story has revealed the hate, ignorance and fear that so many Americans harbor. In addition to the threatening emails that both he and I received saying that we advocate terror and genocide, the “comments” stream on both the NPR and Washington Post websites have some striking responses. One is always reluctant to anoint or give added value to these reactionary responses shot out into the world from behind veil of anonymity by citing or quoting them, but the “Building Bridges” initiative is meant to expose and to combat reductive and harmful stereotypes about Muslims, and so it seems worth noting how many comments like these have surfaced.

Smart to keep them out...we don't need go be watching what one more crazed Muslim is doing in our countr...Just ask the Euros'. Sand people belong in the sand...far away where they belong.

After all, its impossible that any of them would want to harm us by flying planes into buildings. Oh wait…

I seem to remember a group of so-called refugees from the central Asia republics fleeing war and applying for asylum in the USA. I seem to remember some time later that the children of those asylum-seekers blew up a bomb at the Boston Marathon.

As we see in the news every day, month after month, year after year, Muslims are extremely dangerous people. Muslims hide behind the deception of their religion. Many years and generations will have to pass for people of the Muslim faith to prove themselves worthy of being peace seeking people, allowing them freedom to promote their culture through the arts, politics and other worthy professions.

These kinds of reactions offer a stark reminder of the importance of the “Building Bridges Initiative” and help set the agenda for our two-year Myriad Voices Festival.

***

When we were at the border about to cross into Jordan, my husband told me to look back at Syria for one last time, because we might never see it again.

—Suaad, Syria: the Trojan Women, describing how she was moved by Queen Hecuba of Troy’s speech about never seeing her country again

In his article Omar Abu Saada’s The Trojan Women: Rethinking the Public with Therapeutic Theatre, Ted Ziter describes the significance of Syria: The Trojan Women,

Refugees become artists, demonstrating an ability to make use of their past experience, at the same time that the combination of voices demonstrates different responses to war. The playing space becomes an open discursive field in which varied understandings of the self become platforms for new understandings of the nation. In the process, these artist/refugees trouble the boundaries between the private and the public, potentially creating a new public sphere that is not only revolutionary in its critique of entrenched political power but in its reformulation of the idea of the public itself.

The Laboratory for Global Performance and Politics at Georgetown was founded to bring the world of performing arts and international policy together, and it’s hard to imagine a project that better reflects both the immediacy and importance of this convergence and the complexity of this interaction. Our experiences over the last nine months, in which our team has spent many hundreds of hours working to try to bring this piece to DC, have surfaced the biggest fundamental questions about the role of artists and storytellers in crossing literal and figurative borders.

The Voices Unheard Summit is above all an act of solidarity with the women. It is an attempt to share all we are able to of this project that has so moved us, and that strikes us as such a timely and urgent antidote to the picture of Syria created by the current ISIS-dominated news-cycle.

We also envision the summit as part of a process of constructive public dialogue for the wider community to better understand our visa policies and procedures, and to reckon with why it should be so difficult to host a group of women who have suffered so much and who want only to share their stories. We are heartened that the project will tour to Switzerland and perform at CERN in Geneva this fall.

Ziter asks poignantly: “Can the personal reflections of female refugees—their observations on a work of ancient literature, recollections of cherished girlhood experiences, and descriptions of violence and forced migration—become the means of redefining the common good?” Despite the widely varied and often contradictory opinions and responses we have heard from governmental officials about the visa process, we continue to hope and have faith that public sentiment, advocacy and resilience will win the day, and that before long, we can welcome these women in person. Then, almost 2500 years after Athenians gathered for Euripides’ play, we will gather in our nation’s Capitol to witness Syria: The Trojan Women in its fully-realized form.

My name is Nadine and I am 23 years old. The character I love most is Hecuba. My favourite line that she says is, "Oh world! Do you witness what we suffer? Our race doesn’t deserve this treatment.” I feel that this line speaks to us. We used to live a beautiful life before all this and now we are nothing. —Nadine, Syria: The Trojan Women

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here

Euripides' play was, as Goldman noted, written and performed at a time when Athens' own treatment of the women of defeated nations was being called into question. It is an easy thing to perform Trojan Women in the United States: American foreign policy is not above criticism, but on the treatment of women, the Americans are not Achaeans. The question is: When will such a play be able to be performed in the Arab world? (Or, in consideration of what happened 15-20 years ago in the Balkans, has it been performed in Belgrade?)