The Neo-Futurists' The Miss Neo Pageant

Heading to Andersonville to see The Miss Neo Pageant, a “feminist play for accidental feminists”, I was totally preoccupied by an enormous zit that had erupted on my chin. At thirty-five, I sometimes like to believe that I have outgrown this sort of self-consciousness (not to mention, this sort of breakout). Yet I had spent the afternoon with my best friend, hiding my chin behind my hands while envying her always-perfect skin.

Miss Neo looks at the contradictory, complicated pressures mainstream middle-class American society places on women—and women place on themselves—as they attempt to become “grown ups.” Have a healthy relationship with food, but be athletic and slender. Maintain close relationships with female friends and kin, but always be just a little better than them. Cook and create and craft a perfect nest to be a domestic goddess, but do it all effortlessly. Be assertive but don’t be a bitch. Be sexy but not slutty. Be successful but not threatening. This critique is not radical, nor is it sold as such. Miss Neo jokingly references mainstream contemporary feminist sources such as Jezebel and The Ethical Slut, acknowledging that many members of its audience regularly consume stories about these social pressures. The problem the play highlights, but does not attempt to solve, is that even when women are aware of these problematic dynamics, they continue to engage with each other as if all of life were an endless competition.

The problem the play highlights, but does not attempt to solve, is that even when women are aware of these problematic dynamics, they continue to engage with each other as if all of life were an endless competition.

On the night I saw the show, eighty to ninety percent of the audience appeared to be white women between the ages of twenty and forty. Created by Megan Mercier, directed by Stephanie Shaw, and written by the ensemble, Miss Neo is in many ways a play created by and for middle class, educated, relatively young white women. The play does not claim to deal with race or class—its focus is explicitly on gender—but as a result it focuses exclusively on a set of problems faced by a small group of relatively privileged women. Mainstream feminism has often been criticized as focusing too intently on the interests of middle class white women, and Miss Neo can certainly be critiqued for these reasons. However, in its tight focus, it operates as community-based theater, created by and for a specific segment of the population to deal with problems plaguing that group.

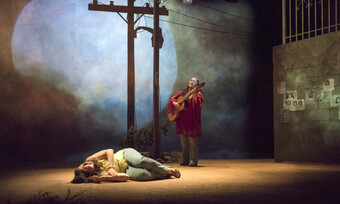

The Neo-Futurists are best known for their long-running late night production Too Much Light Makes the Baby Go Blind, in which the ensemble attempts to perform sixty plays in sixty minutes. Drawing inspiration from Italian Futurism, Dada, and interactive experimental theater traditions from the 1960s, the Neo-Futurist aesthetic is fragmented, fast-paced, low-tech, and often quite funny, with little to no distance between actor and character and actor and audience. The Miss Neo Pageant utilizes this aesthetic through the framework of a highly engaging ironic beauty pageant, as the ensemble is introduced wearing leotards, fishnet stockings, sparkly silver shoes, and sashes bearing titles like “Seething Rage” and “Not Gonna Cry” designed by Lara Miller, and the back wall to the playing space is made up by scenic designer Nicci Schumacher as if it were a women’s dressing room with mirrors and racks of costumes the women change in and out of within view of the audience.

The play is dosed liberally with pop culture references to the late 80s and 90s to speak explicitly to an audience of women who came of age, as Megan Mercier states “during prime ‘Girl Power!’ time.” A dance number to Shania Twain’s “Man! I Feel Like a Woman” invokes, in me, memories of many a late-‘80s suburban dance recital, complete with jazz hands and a kickline. This dance is repeated many times throughout the evening, gathering meaning with each repetition—sometimes the ensemble dances with huge grins, sometimes with blank dead eyes, once to the soundtrack of a male voice instructing the women in a string of clichés, “love like you’ve never been hurt, dance like nobody’s watching, hakuna matata.” The dance speeds up to manic pace, leaving the contestants raggedly attempting to complete all the steps. In this moment, I am reminded of Courtney Martin’s wry observation that girls raised in the wake of the second wave of feminism were told we could be anything and heard we had to be everything. Miss Neo recognizes this problem and represents it but does not claim to offer solutions to it.

In keeping with the NeoFuturist aesthetic, Miss Neo’s structure is episodic, many moments are openly absurdist, and the piece as a whole defies a stable, singular meaning: Molly Plunk walks a tightrope, clearly trying to impress her audience with ever more complex tricks. She never falls, but there are moments when it looks like she might. When she finally steps back onto the platform at the end of her rope, actor and audience members all breathe a sigh of relief together. In another moment, a trio of women in sequined dresses make coffee, moving in elegant, graceful strokes to “The Flower Duet” from Léo Delibes’ opera Lackmé. They elevate the filter cones on spangled pedestals, gently pouring hot water over them, and ultimately serving cups to members of the audience. Audience members are left to interpret these actions for themselves.

The piece is, at times, openly interactive, and audience members are called onstage to directly participate in the action. In one such moment, an ensemble member and an audience member are asked a series of questions under a glaring light. Your name, your age, your relationship status. What are you afraid of? Do you compete with other women? Are you comparing yourself to the woman sitting next to you? From my seat, I silently watch the offbeat beauties onstage and realize I am, indeed, comparing myself to the women onstage—wishing I had hair as cool as Molly Plunk’s, tattoos as badass as Tif Harrison’s, a body as strong as Leah Urzendowski Courser’s. I hide my chin behind my hand and soothe myself with the knowledge that I fit into my size zero skinny jeans. As I realize I am doing this, I beat myself up a little. Isn’t this reaction in direct opposition to the production’s central message? What’s more, shouldn’t I know better? The “pageant” highlights the absurdity of the ways women compete with each other—pointing out how often women do it and how deeply this competition embeds itself in our relationships with each other. Yet even in the midst of reflecting on how problematic this is, old habits die hard. Miss Neo does not attempt to reconcile this contradiction. It instead opens up a space for me to reflect on how I might take small actions to address these issues in my own life. Even if I still try to hide the occasional offending spot behind my hand.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here

Thanks, Dani! It's great to read such an honest and intelligent response to the Miss Neo Pageant!