Disability’s Many Meanings

Disability is complex. Being born without a limb may hold a different story than losing a limb to chronic illness, to war, to purposeful maiming into silence, to poverty, to race-based violence, and beyond. Each hold profoundly different histories that are brushed over by that single word. I sometimes find myself resisting using “disability” without contextualization due to the endless amount of preconceived ideas, discriminatory attitudes, and lack of understanding of the many worlds this word holds.

My hypothetical example of living without a limb touches only one easily identifiable physical disability and ignores the unique languages of cognitive diversity. Yet it illuminates how each story of a body-mind demands its own structure of telling. And, given the historic and continuing stigma and oppression of disabled people, its own retelling. While words can at times be limiting, art and poetic thought can move us to a much deeper engagement.

I began to articulate the knowledges that arise from living with disability through puppetry and physical theatre performance in 2013. I brought my work primarily to disability and clinician communities across the United States and Canada. I developed a pedagogy for clinician training, Embodiment and Puppetry, and was selected to be a Kienle Scholar in the Medical Humanities for my interdisciplinary artistic research. Until 2018, I insisted on working nearly exclusively in medical contexts. I realized medicine had taught me a broken, ableist relationship to my body-mind.

My driving purpose was to awaken imagination, feeling, and disability consciousness within medicine through the arts and to create change. Yet I began to hunger for the freedom of the stage, for the purity of artistic articulation that does not have to be constantly in reference to the medical gaze. I now work across artistic, medical, academic, and activist circles. Each space has its own unique challenges, possibilities, and limitations.

Puppetry for disability aesthetics and justice is expansive, and the last thing I would want to do is write a set of proscriptions for artistic work. What follows are a few guiding principles for artists to consider when approaching puppetry work that can help avoid disability essentialism and the ableist gaze. First, though, I must acknowledge the visionary work of Sins Invalid, which centers queer, non-binary, and trans people of color with disabilities. They are foundational in pushing forward cultural organizing, intersectional disability arts practice, and the principles of disability justice.

The extraordinary language of puppetry animation holds within it a unique capacity to disrupt and interrogate the able-bodied gaze and normativity.

Defining Disability Aesthetics

Disability aesthetics is reimagining the fabric of what is meant by “aesthetics” altogether towards the goals of disability justice. This aim “recognizes the intersecting legacies of white supremacy, colonial capitalism, gendered oppression and ableism in understanding how peoples’ bodies and minds are labelled ‘deviant’, ‘unproductive’, ‘disposable’ and/or ‘invalid.” It is a fundamental reimagining of moral equality, worth, and beauty. (I also recommend reading Tobin Siebers’ Disability Aesthetics.)

One way to think of disability aesthetics is as artists embracing and incorporating elements into their practice that are often excluded from able-bodied assumptions and biases about bodies, minds, and beings.

A recent staging of Not I, part of the Public Theater’s Under the Radar Festival this year, is a brilliant theatrical (non-puppetry) example of this. In performer Jess Thom’s reimagining of Beckett's fifteen-minute stream-of-consciousness play, she actively incorporates her mouth that must at times shout; her Tourette’s is interwoven into the foundation of the performance. She then further actively disrupts the able-bodied gaze through what happens post performance, which includes getting the audience to watch a video. As a Slant reviewer noted: “It’s only during this [video] section of the performance—a few minutes in which Thom herself is not visible as she sits in the dark—that I reverted to experiencing Thom’s tics as disruption or interruption.” This awareness was not an accident, but the result of the specific choices made by the artist. Thom wants audiences to become aware of their able-bodied gaze and affective responses to her body-mind, and she succeeds brilliantly. Her choices challenge, disrupt, and reimagine cultural, artistic, and medical responses to disability.

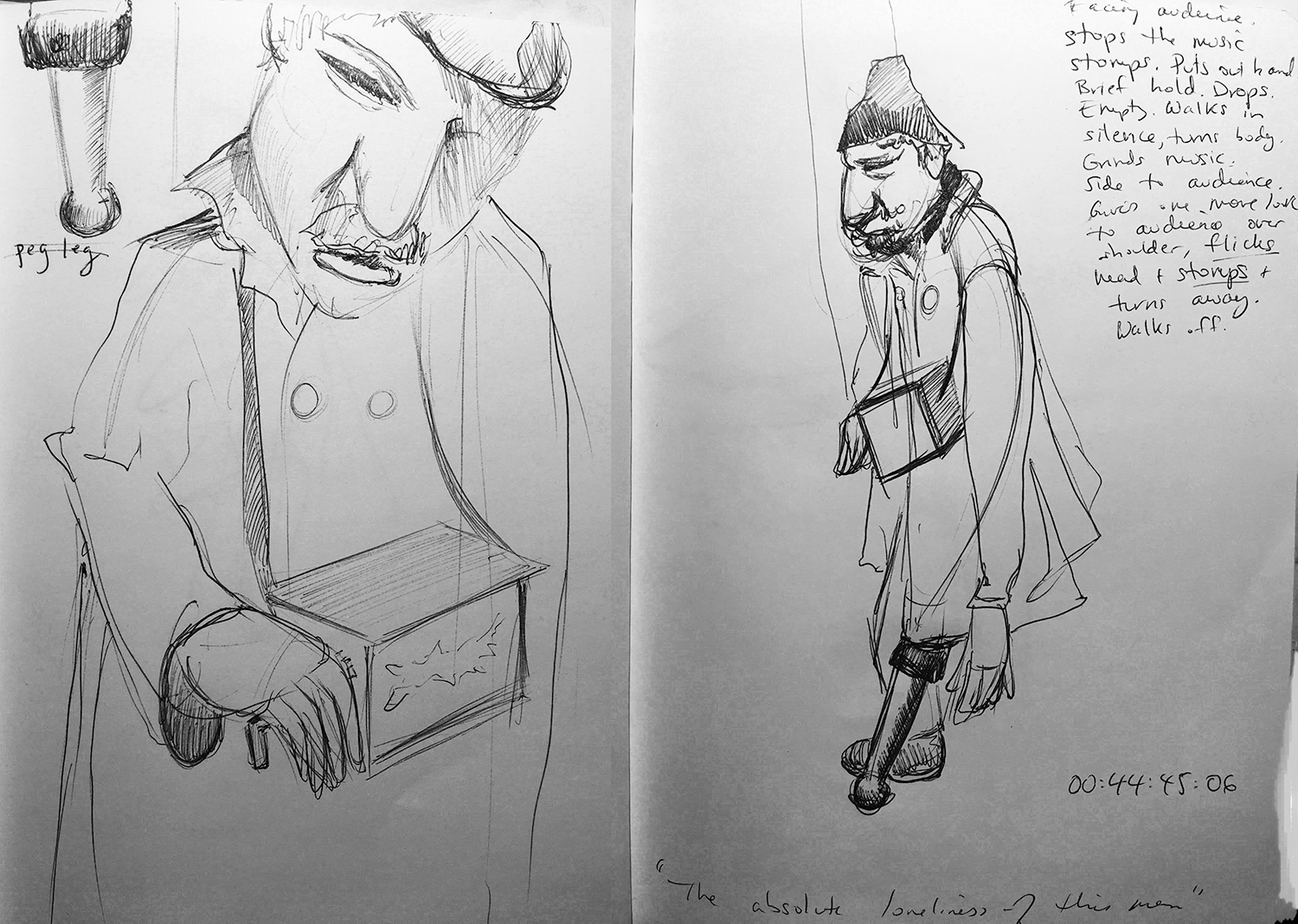

A puppetry performance that I staged on chronic illness and loss, The Invisible Elephant Project, works along similar lines. At the height of the twenty-two-minute solo performance, I as the puppeteer quietly but visibly remove one of the puppet’s legs against the puppet’s will. The puppet then later kicks off its other leg. When I played it in 2017 at a hospital to a room of clinicians, caregivers, and people with diabetes, someone in the audience gasped “that’s disgusting” in response to this moment.

If the response of disgust is elicited at the removal of a puppet limb, what does this say about the relation someone can hold to their own body or the body of another? How does this response shape practices of care? I don’t think it needs to be said that disgust and violence do not live far from one another. I was aware of the complexity and depth of what I was opening by staging that moment. In part because I myself live it, because of the time I have spent listening to the experiences of others, and my commitment to disability justice.

It is my artistic duty to push and pull against the able-bodied gaze and elicit these questions. Like Not I, The Invisible Elephant Project incorporates carefully facilitated reflective conversations to unpack what was awakened during the aesthetic experience of the performance. That is where the work of social change occurs.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here

This article is brilliant! I am developing a cultural project using puppetry for and with a small disabled community. And so this material is very helpful.

This article was great! I'm constantly looking for new ways to explain ablism to the abled community. This is helpful.

Thank you so much for reading and commenting. It's great to meet on this platform. Ableism is so deeply ingrained- one of my goals in writing this essay was so it could serve as a teaching tool to #CripTheArts and educate about ableism. :) If you have other arts-specific articles that you've found helpful in this regard, maybe post a link here? Can be a nice way to pool resources.

Another resource I really love is Bodies in Translation <--- they explicitly state:

"Projects that speak to experiences of disability must be led by disabled people or people who have lived experience of the intersections of embodied difference."