Throughout this scene there is not a piece of physical glass in sight, as no props or set is used beyond a small toffee hammer for each performer. This violent sequence lasts for a fleeting moment. The production did not dwell on the embodiment of militant activity from the Suffragette era; rather this representation played down the extremity of the movement’s behaviour. By marginalizing this side of the narrative, the extremes that early feminists went to were belittled.

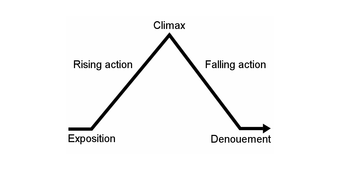

In contrast to this non-naturalistic staging, the representation of forcible feeding in Her Naked Skin confronts audiences with a detailed re-enactment of an act of torture many Suffragettes endured. The fictional action begins with prison guards leading Eve into a doctor’s office, where she is instructed to sit down while her legs and hands are tied together. A nurse holding a long tube, funnel, and flask of liquid stands on a chair next to Eve. Guards and nurses hold Eve still, and with two guards holding her face in position Doctor Vale begins inserting the tube, attached to the funnel, into her nose. Vale clarifies that the tube needs to be pushed “in a good twenty inches […] so it goes right through to the stomach.” Once the tube is in place, Vale directs the nurse to pour the flask of liquid into the funnel. As Eve’s body shakes in reaction, Vale calls for a wooden gag, which Eve resists and spits out, so a metal gag is demanded. The guards force it into her mouth as Eve thrashes her limbs, attempting to fight them off. Once the nurse has declared that all the liquid has been poured into the funnel, Vale slowly removes the tube. When the final part of the tube is removed Vale bends down to look at Eve and she vomits over him, which he reacts to by slapping her across the face.

This dramaturgy has ideological implications: while the extremity of the Suffragettes’ actions are overlooked, their subsequent punishment frames them as victims rather than political radicals.

Critics’ responses to this production of Her Naked Skin emphasized the realist and violent staging of the forcible feeding sequence. Michael Billington described it as “one of the most horrifying scenes on the London stage,” while Georgie Hobbs observed that “six people walked out, as I had wanted to.” However, Hobbs goes on to question such visceral responses arguing, “You’re supposed to know what you’re signing up for in a play about suffragists largely set in Holloway Prison; force feeding is expected.” For Hobbs, the recurring narrative of forcible feeding in suffrage drama should have caused desensitisation on the part of the viewer, not offending them to the point of leaving the theatre. However, it appears that this expectation pushes theatremakers to create a more visceral and harrowing reimagining of forcible feeding, rather than exploring an alternative mode of representation.

In stark contrast to this climactic reenactment of forcible feeding, the window-smashing scene functioned primarily as a plot device to provide a reason for the women to serve time in prison. This prioritization was reflected in the set design. The window-smashing sequence took place on a bare stage with a general lighting wash. This is not to say that a complex set is necessary to validate the action, but this choice stood out as the majority of the following scenes used a revolving set to provide props, furniture, and large structures to illustrate the different settings, from Holloway Prison to a tearoom. For example, in the forcible-feeding scene, the action took place with prison cells as its backdrop and the medical equipment used echoed those described in Suffragette accounts of this act of torture.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here