On Wearing Two Hats

Why Playwrights Should Work in Literary Management

I’ve considered myself a playwright—of one kind or another—since I was ten years old, when I first started writing and staging twisted variations on fairy tales in my parents’ backyard. I’ve considered myself a professional playwright—of one kind or another—since 2010, when professional theatres began producing my plays. And during most of that time, I was under the misconception that “being a playwright” consisted mostly of sitting at my computer writing plays, and sometimes sending them out to theatres that might want to consider producing them.

Then, about a year ago, Project Y Theatre Company approached me about becoming their literary manager. I’d worked with Project Y as a playwright—they’d produced one of my plays a couple of years before and done readings of several others—but it was my first time joining the staff of a company. As literary manager, I help to curate the reading series and find plays for possible production, and I’ve also founded a playwrights’ workshop, the Project Y Playwrights Group, under the auspices of the company. I’ve found doing literary work to be incredibly helpful to me as a playwright, in both predictable and unexpected ways.

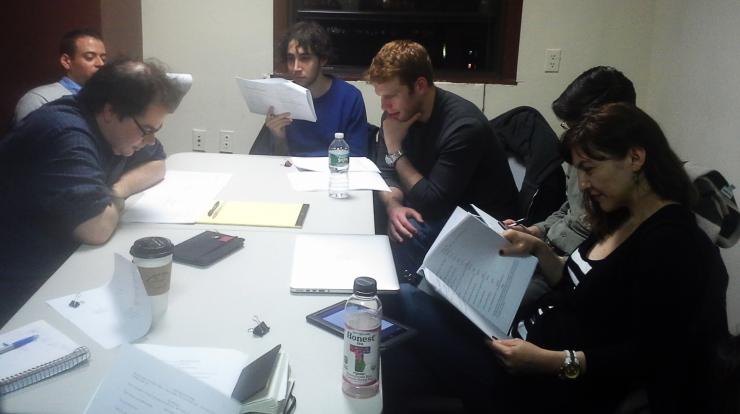

Photo: Project Y Playwrights Group.

First, the obvious: reading a lot of plays has made me a better writer. In order to write new plays, you need to read new plays, and unless you feel like spending a lot of time and money at The Drama Book Shop, the best way is to get involved as a literary manager, a literary associate, or a script reader. Along the same lines, reading a lot of query emails and cover letters has made me a better writer of query emails and cover letters, and reading a lot of resumes has made me a better writer of resumes. By seeing the ways that other writers approach me, I’ve been able to get a sense of what works and what doesn’t, and apply that knowledge to the ways that I approach other theatres.

Ever since I’ve become a literary manager, networking has become much easier. Instead of feeling like I’m just asking for something, I feel like I have something to offer. I want to meet playwrights and directors, because I might be able to connect them with my company… and it’s an added bonus if they might also be able to connect me with theirs.

A less obvious benefit of doing literary work has involved networking. I’ve spent most of my career dreading events where networking is necessary. I’m shy. I often have trouble talking to strangers, or trying to sell myself. I have a hard time even asking friends to watch my dog for the weekend, let alone asking a theatre company to consider sinking hundreds of hours and thousands of dollars into a production of my work. But ever since I’ve become a literary manager, networking has become much easier. Instead of feeling like I’m just asking for something, I feel like I have something to offer. I want to meet playwrights and directors, because I might be able to connect them with my company… and it’s an added bonus if they might also be able to connect me with theirs. It’s allowed me to relax and to realize that “networking” can just mean meeting interesting people and talking about interesting work—which can actually be a lot of fun.

Being involved with a company has also given me a better understanding of what goes into production. I’ve had short plays in a lot of short play festivals, but until I helped to produce one, I didn’t understand the sheer volume of logistics involved in trying to coordinate multiple plays, playwrights, directors, and casts. Similarly, until I started attending company staff meetings, I had no idea how incredibly expensive it is to mount even a modest NYC production. It reminds me of Michael Pollan’s maxim that if you’re going to eat meat, you should—at least once—have the experience of hunting and butchering your own. Writing plays is hard, but producing them is really hard, and seeing production from the other side can help playwrights be engaged and responsible members of the theatre ecosystem.

There are many companies out there with piles of scripts to get through, and many of them could use some help. So writers, I’d encourage you to reach out: pick a company whose work you admire, contact them, and see if they need any assistance in their literary department (or anywhere else). It doesn’t have to be a major time commitment—some larger theatres have structured, full-time internship programs, but smaller companies are often happy to have whatever help you’re able to give them. If you can’t find a company to connect with, there are lots of contests and festivals that receive hundreds of scripts each year and need people to read them.

You’ll read a lot of less-than-brilliant plays. That’s okay. It’ll make you feel better about your own work, and help you figure out what not to do in the future. And you’ll read a lot of really good plays, amazing plays; the biggest surprise since I started working as a literary manager has been seeing how many amazing plays are out there, many of which were written by writers I’ve never heard of. I believe in my work, and during the stretches when I’ve felt like it wasn’t getting produced enough, I’ve been tempted to wonder what’s wrong with it—or with me. But in seeing how many amazing writers are in the same position, I’ve realized the answer is: nothing. It’s just really hard. Which is actually, oddly, encouraging. And I’ve been able to help some of those writers develop their work or get it out into the world, which is even more encouraging. Many of us are ultimately in the theatre because we love good plays, and doing literary work is one of the best ways to make your own plays better and more successful, as well as to help bring attention to good plays by other writers.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here

How would you advise dramaturgs, playwrights, and theatre practitioners in general finding these small theatres that allow people to enter the conversation by working as an assistant literary manager or intern. I am currently a Theatre Studies student at LSU, and I am very anxious about connecting my studies to theatre in the "real world." If you have any words of wisdom, please let me know. Wonderful blog post!

Hi Alexander - just saw your comment, so apologies for the delayed reply! I've found small companies to be very open to people who want to help. Identify the companies in your area whose aesthetic lines up with yours, and then just send them an email and ask if there's anything you can do! - if you reach out to enough people, you will definitely find a match eventually.

Well worth reading. Aside from recommending work in literary management, the post calls attention to the many people writing good and bad scripts, thereby creating a lot of work screening them,

This is so so so so true! Thank you for putting it out there! Until I started my own playwright's group through the Dramatists Guild, I felt much less connected to the theatre, to other playwrights, and to a community I could call my own. I also read for a few small theaters, and it does help me to see what's out there, and to understand better what great scripts have to offer these days. I am also working part-time as a dramaturg for different festivals and theaters (on an as-needed basis), and I love the work. For the sheer joy of getting to hang out in new dramatic material, in someone else's narrative structure, to search for the sense in the maze of it all, to have a piece find itself from the first to the second reading, all of these things are rewarding and inspiring to me.

Thanks for posting, Lia. I've felt awkward and unsure about wearing both of these same hats since I began dramaturgy work a few years ago. As an Early Career Dramaturg and playwright, it's nice to hear what works in borrowing and living in both of these roles. I hope I can put your advice to work, especially as a script reader, soon!