Williams and Shakespeare

The 12th Annual Provincetown Tennessee Williams Theater Festival

On a dark and stormy night, individuals sporting full-body ponchos and broken umbrellas traverse to the far edge of a wizened wharf. A wharf unpretentiously covered with a century’s worth of nautical accoutrement and jutting out nearly a quarter mile into the freezing waters of Cape Cod. Upon reaching the very end, the travelers find a homely shack—dark, damp, and creaking as each new gust plays upon its wooden frame. And yet inside, lights are set, rows of seats are arranged, and an audible buzz of excitement fills the confines of the room.

Why? Because a show is about to begin. Hamlet, in fact.

September 21–24, 2017, marked this year’s Provincetown Tennessee Williams Theater Festival, one of several major Provincetown arts festivals and the only one which celebrates the town’s distinct theatrical heritage. Williams spent four of his most formative summers in Provincetown perfecting his craft and awakening his sexuality—culminating in the summer of 1947 which saw him make the finishing touches to A Streetcar Named Desire. However, the festival has far outgrown the need to rely on masterpieces like Streetcar in order to find an audience. Instead, the festival’s curators are much more interested in exploring Williams’s forgotten, misunderstood, or otherwise unknown works and reinterpreting them in fresh, new ways. Furthermore, following in the footsteps of last year’s festival which incorporated plays by Eugene O’Neill, this year a foil for Tennessee was found in the Swan of Avon: Shakespeare himself. Eight performances by the pair of playwrights were staged in seven very different venues, ranging from Provincetown’s majestic Town Hall to the desolate rooms of a real-life hotel.

Such is the reason that Hamlet, a pinnacle of theatrical tradition and high culture, could be found in such austere circumstances only several feet above the open ocean (and during a tropical storm, no less). In fact, the show’s company couldn’t have asked for better conditions. Their concept of the play was inspired by a little-known piece of history: the very first production of any Shakespeare play outside Europe occurred aboard the Red Dragon, an East India sailing vessel whose shipmates performed Hamlet off the coast of present-day Sierra Leone in 1607. This production, presented by Abrahamse & Meyer of Cape Town, South Africa, was framed as the nightly entertainment of a group of six restless sailors trying to pass the time while on a lengthy voyage. Each actor/sailor played multiple parts, wearing suggestive costumes on a barebones set that highlighted the sailors’ DIY spirit and gruff, seafaring heritage. Presenting Hamlet in this manner imbued the play with a dark, primal power, one that makes abundantly clear humankind’s capacity for self-destruction.

And this wasn’t the only company embracing marine aesthetics. Another Shakespeare play was performed with a similar concept but for much different reasons—Philadelphia’s newly-formed Die-Cast theatre company presented Pericles aboard the enormous replica of the Rose Dorothea schooner that has graced the Provincetown Library’s second floor since the 1980s. The play is one of the Bard’s most muddled and least understood—partly because it’s now commonly agreed that Shakespeare himself only wrote Acts III–V. The tale of a Mediterranean prince who solves riddles, wins the favor of foreign powers, and ultimately finds a happy ending certainly sounds entertaining when summarized. But the play’s wildly erratic structure, scores of characters and locations, and strange obsession with incest and prostitution have historically made it hard to present. I was therefore impressed by this production, which found deeply inventive ways to rise above the play’s flaws and discover a certain beauty in the unknowable mysteries of human fate—mysteries that, like the wind and water which govern a ship’s course, constantly change without our consent and quite often against our good fortune. A tightly-knit company, directed with care and scrupulous detail, both honored the text and transcended it by finding power in choreographed gestures, varied vocal dynamics, original music and sound, and above all, a playful attitude toward their one-of-a-kind set.

Another standout was Ten Blocks on the Camino Real, performed by actors from the National Theatre of Ghana based on Williams’s original ten episodes (“blocks”) from the surrealist Camino Real. The play was presented outdoors, in Provincetown’s Bas Relief Park, using a group of energetic actors and a musician punctuating the action with kpanlogo drums and xylophone (cleverly, the drumming was also used to mimic the beating of Kilroy’s oversized heart). What interested me most was that the actors in this production, while all able to speak English as a second language, conveyed a markedly different sensibility than a typical Williams production. The Ghanaian troupe’s unique blend of liveliness, sincerity, and generosity broke the usual Williams expectations of delusion, ambition, and deep cynicism. From resisting these tropes and presenting the play in a highly engaging manner, Ten Blocks was actually able to delve deeper into just what makes Williams’s life and legacy so immortal.

But, of course, sometimes we learn the most about Williams by mining these very tropes to their greatest depths. Such was the case with The Gnädiges Fräulein, a long-forgotten comedy about brassy women (and bizarre birds) in a tight-knit village on the Florida Keys. A gossip columnist becomes fascinated by the strange goings-on at a makeshift hostel, particularly its no-nonsense landlord and one of her tenants, the titular Fräulein: an ex-singer from Eastern Europe, quickly losing both her senses and, because of some angry birds, her organs. Presented by Texas Tech University in Lubbock and directed by Festival Director Jef Hall-Flavin, the play’s ridiculous plot was sharpened rather than smoothed by three sensational comedic actresses and a set and costume design straight out of an expressionist cartoon. The production met the complicated play head-on, and was therefore able to isolate Williams’s unique comic flair to great effect.

What was made abundantly clear…was how these two playwrights [Williams and Shakespeare] thrive by forcing larger-than-life characters into increasingly desperate situations.

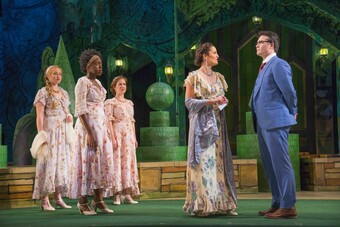

But all of these performances (and others) still didn’t illuminate for me the through line between Williams and Shakespeare—each is pleasurable separately, but surely there must be some stronger link between them to tie the festival together. Luckily, these concerns were addressed with my favorite show of the festival: The Hotel Plays, presented by Spectrum Theatre Ensemble of Providence, Rhode Island (in association with Trinity Rep). This was an immersive production, taking place in Provincetown’s Gifford House Inn and Porchside Bar. Texts by both playwrights were presented, most significantly Williams’s Talk to Me Like the Rain and Let Me Listen, and Mister Paradise and scenes from Shakespeare’s Cymbeline and The Comedy of Errors. What was made abundantly clear through all of these texts was how these two playwrights thrive by forcing larger-than-life characters into increasingly desperate situations—in fact, they thrive precisely because they’ve found this to be the true essence of all dramatic conflict. In one room, a princess about to meet her doom finds an avenue for escape by disguising herself as a boy. Next door, an aging poet, holed up in a room littered with discarded manuscripts, is visited by an idealistic young girl: his greatest (and perhaps only) fan. Upstairs, two lovers awaken on a lazy Sunday morning to confront their uncertain futures, and at the bar, two men celebrate their burgeoning relationships, even if said relationships are actually the result of misunderstanding and deception. In the program, the production’s creative team likens each of these rooms to a pressure cooker—tight spaces ready to burst at any moment from high concentrations of desire and discontentment. I’m certain it wasn’t just the humidity from the storm that made that pressure so potent.

Regardless of how exactly these two writers fit together, they nonetheless proved to be compelling source material for this most remote of all theatre festivals. Provincetown, because of inhabitants like Williams and Eugene O’Neill, is often called the birthplace of modern American theatre. It was heartening to see, based on the quality and range of the productions presented this weekend, that it strives to be the home of experimental contemporary theatre as well.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here