August Wilson Takes New York

“Over the next five weeks,” announced Ruben Santiago-Hudson on the opening night of the monumental and historic August Wilson’s American Century Cycle recording series in New York, “we plan to set this city on fire with the spirit, passion, integrity, and truth of August Wilson.”

That was on August 26. By the close of the series at The Greene Space on September 28, staged readings of Wilson’s plays and their live video webcasts had been viewed by many in NYC and beyond. The plan is to make available audio recordings of all ten plays on The Greene Space website and broadcast select plays on WNYC and public radio stations across the country in early 2014. Video of the August Wilson Talk Series and photos of the readings are available here.

In little over a month, the series produced staged readings of all ten plays in Wilson’s signature cycle, and complemented the performances with six different events in a Talk Series that invited some of those who worked closely with Wilson to share their experiences and insights. All events were recorded live at New York Public Radio’s Greene Space in lower Manhattan and streamed in real time to internet audiences. The series sought to capture, honor, preserve, and share the essence of August Wilson, both the aesthetic beauty of his plays and the enormous emotional impact he and his work continue to leave on generations of audiences.

The series sought to capture, honor, preserve, and share the essence of August Wilson...

And it succeeded marvelously on all counts.

Guided by the vision of executive producer Indira Etwaroo and the artistic direction of Ruben Santiago-Hudson and Stephen McKinley Henderson, the series assembled six directors who have proven themselves the finest curators of Wilson’s work and over sixty first-rate actors in order to present these ten plays as vivid, living testaments to the history of one playwright, of the black experience in the US, and of American theater and culture more broadly.

The result was to transform the Greene Space at the corner of Varick and Charlton in SoHo into 1839 Wiley Avenue in Pittsburgh’s Hill District, the home of Aunt Ester, spiritual mother to all Wilson’s characters.

1839 Wiley—the house with the red door—and Aunt Ester herself show up only in Gem of the Ocean (which was the only play in the series that was produced on a Tuesday—Aunt Ester only sees people on Tuesdays, after all), but the woman and her home remain the anchors for Wilson’s project of examining the twentieth-century black experience in America. Aunt Ester is 285 years old in Gem of the Ocean, set in 1904, and 366 years old when she dies in King Hedley II, set in 1985: both ages place her birth in 1619, the year African captives first set foot on American soil, the point at which Wilson said his history began. Aunt Ester stands as the genealogical link to the earliest moment in that history, and one of Wilson’s most prevalent themes is excavating and connecting the stories and events of a suppressed past. As Holloway repeatedly insists in Two Trains Running, 1839 Wiley is a place where folks can go to gain an understanding and achieve a sense of peace; in Gem, Citizen Barlow shows up there in the hopes of having his soul cleansed.

Over the month of September, New York’s Greene Space became at once the location and vessel for remembrance and awakening. Folks on stage and in the intimate audience shed tears as freely as they laughed or hugged heartily. By the time the series concluded with Harmond Wilks applying war paint and heading out to recapture his soul by protecting Aunt Ester’s house at the close of Radio Golf, “August Wilson’s American Century Cycle” had established a community who could share a rare and powerful experience centered on the art of a man who sought to foster just such a community.

And so while the Greene Space’s time as the spiritual locale of 1839 Wiley was fleeting, those who assembled there—black and white and of all ages, some for one or two plays and some for all ten—were rewarded with the same spiritual understanding that Aunt Ester provides Wilson’s characters.

The series’ dramatic success was no less substantial than its emotional impact. Wilson’s cycle—ten plays set in the ten decades of the twentieth century—is remarkable in the depth and breadth of its achievement. So few authors complete planned cycles, but Wilson managed to do it even while staring down liver cancer in his final years. The vast world he created in his cycle is one marked by penetrating insight, profound understanding, and deep compassion paired with unromanticized truth. To bring all of those achievements together under one roof in the span of a month and to bring it to life in the voices and visions of so many talented artists is nothing short of miraculous.

The short time span of the performances highlighted especially the themes and tensions that weave themselves throughout Wilson’s plays. When Radio Golf’s Harmond Wilks announced that his grandfather was Caesar Wilks a knowing sigh came from the audience at the Greene Space, many of whom had met the infamous Caesar only four days earlier in the performance of Gem of the Ocean. Radio Golf is a sequel to Gem, but the two plays have never been presented within a time span that so clearly underscores their connections (perhaps the benefits of doing so are now clear, and some wise theater will run the two plays in repertory…).

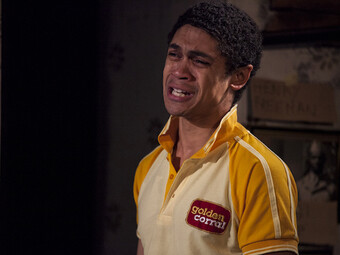

The same is true of Seven Guitars and King Hedley II, which were presented eight days apart: the first featured Ruben Santiago-Hudson as the vibrant Canewell and Cassandra Freeman as the vivacious Ruby of 1946, and the latter gave us Arthur French as Stool Pigeon, the stalwart mystic into whom Canewell ages by 1985, and Leslie Uggams as Ruby after a rough adulthood full of mistakes and their repercussions. Owiso Odera introduced us to a kinetic and eager Sterling Johnson in Two Trains Running, and less than three weeks later Eugene Lee gave us the elder Sterling in Radio Golf, equally kinetic and eager but more jaded and savvy about trouble in the community; whether he is fighting for Hambone or Elder Joseph Barlow, this series made vivid Sterling’s unfailing commitment to support the weak and disenfranchised.

Among the series’ many goals was to reassemble as much as possible the casts and directors of the plays’ premieres or Broadway productions. This was of course a lofty goal with varied success, but the efforts did give audiences the all-too-rare opportunity to experience again or for the first time some of the most notable performances in the production history of Wilson’s work. The benefit of working with a playwright as contemporary as Wilson is that many of the actors who have come to define one of his characters are still active and eager to reprise their role. Santiago-Hudson was Canewell in the 1996 premiere of Seven Guitars, and Stephen McKinley Henderson was Red Carter in the play’s 2006 revival at The Signature Theatre; the series’ artistic directors united excellently with the cast, giving the performance a strong sense of genealogy stretching back to its premiere.

Ebony Jo-Ann reprised her Ma Rainey triumphantly, and the same is true of Anthony Chisholm and Phylicia Rashad’s powerful performances of Solly Two Kings and Aunt Ester in Gem of the Ocean. The Piano Lesson reassembled completely the cast and director of last season’s wildly successful production at the Signature, giving audiences the opportunity to meet Roslyn Ruff’s masterful Berniece again as well as to hear Chuck Cooper, James A. Williams, Brandon Dirden, and Jason Dirden sing “Berta Berta” one more time: a standout moment from the series.

Like the live performances, the soon-to-be released recordings will capture and highlight the power of Wilson’s words. The readings at the Greene Space were little more than actors sitting behind music stands performing roles as they read from scripts—a few gestures or sound effects suggested important actions; only once did an actor leave the stage when his character died; only once or twice did a performer even stand up; nobody read stage directions. This was a series about Wilson’s words in all of their sonorous and poetic musicality, and those words alone are what this project will deliver to future generations. To have captured Wilson’s language undistilled and expertly performed is perhaps this series’ greatest accomplishment and a most fitting tribute to a playwright who so often described the process of writing plays as listening to characters, allowing them to speak to him.

I was honored to be in the Greene Space’s audience for all ten of the readings, and on the final night I was delighted to have a seat next to Ebony Jo-Ann, the woman who opened the series a month earlier as Ma Rainey. During the performance of Radio Golf, she and I laughed together, quipped to each other about the characters, sighed together at Roosevelt’s actions, and as she wept after the play’s conclusion we reminisced about the impact of the play and the series. She and I are separated by race, gender, generation, and profession, but the force of August Wilson allowed us to come together in a shared experience, as I am certain it did for many others. Perhaps more than anything, the “August Wilson’s American Century Cycle Series” succeeded in constructing and uniting a broad and diverse community around “the spirit, passion, integrity, and truth of August Wilson.”

After every performance, the actors would bow and then gesture as a picture of Wilson was projected onto the wall, and the applause of the standing audience would grow only louder. As Aunt Ester presided over 1839 Wiley, so too did Wilson’s spirit preside over that address’s temporary home in the Greene Space, offering a unique experience to those who were lucky enough to have made the trip.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here

Thank you for this, Patrick. As someone who has a deep love for Mr. Wilson's words, his characters, and the way their stories continue to give perspective to my life, I thank you for your report.