“The Book,” Author Said

On Elevator Repair Service’s The Sound and the Fury

Recently at a bar with friends, the conversation drifted to what we visualize when we read fiction. How does the mind translate words into pictures? The consensus was characters’ faces appear blurry. “I can see clothes but their faces are blobs.” “Yeah, like a Francis Bacon painting or something.” “If the characters were in this booth, I’d see the booth and their hands, maybe, but not faces.” “Does the character wear the same clothes in every scene?” “For me, they do!” “I’d say it’s more like dressing paper-dolls.” “For scenes, I see snapshots: for instance, if the characters are walking down a street in Paris: I see that static shot. Or now they’re in the woods. Next slide.” “Like they’re in front of a green screen?”

Did you picture it? Did you see us? Or abstract blob representations of us in front of a stock background?

Ten years ago, when I read William Faulkner’s The Sound and the Fury, I saw blobs. When I see Elevator Repair Service (ERS) perform The Sound and the Fury in June at The Public Theater, I see faces. But the faces are not a one-to-one correspondence. Benjy is mostly played by Susie Sokol, but every now and again by Aaron Landsman. Greig Sergeant plays Dilsey, Versh, a washer-woman, a golfer, Mother, TP, Luster, and Roskus. Vin Knight and Daphne Gaines also take turns as Dilsey, Versh, and TP. And whether their scenes take place on a golf course, in the woods, or at home, the background remains a three-walled set made to look like the Compson living room. The production investigates the chasm between words on a page and the reader/viewer experience. How does one stage the blobs and snapshots of literature?

The production investigates the chasm between words on a page and the reader/viewer experience. How does one stage the blobs and snapshots of literature?

The Sound and the Fury infamously resists visualization. The novel ascended the pantheon of American letters as a progenitor of Modernist “stream-of-consciousness,” with many readers finding the first chapter, narrated by Benjy, the cognitively disabled son of the Compson family, notoriously impenetrable. Faulkner’s prose mirrors Benjy’s stunted communication, the narrative leaps back and forth in time, the action rarely framed. Benjy repeats that his sister Caddie “smelled like trees,” but skimps on the how and why.

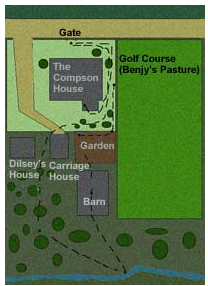

In 2011, scholars at the University of Saskatchewan released a hypertext version of the book as a tool to help teachers and students unpack the chapter. This version rearranges the action to make its characters and settings easier to visualize. It gives the option of reading the text chronologically and provides helpful graphs and a map of the Compson grounds. Faulkner himself second-guessed Sound’s stylistic arrangement, adding the “Compson Appendix” as an introduction and clarification for the 1946 publication of The Portable Faulkner. He and the Saskatchewan scholars seem to want the chapter both ways: as a linguistic experiment in understanding how the disabled see and communicate, as well as a comprehensible narrative easily converted into mind-generated paper dolls and backdrops.

ERS’ staging somehow achieves both. It presents the original text intact, in order, every last word of it, and provides visuals for the readership/viewership. Yet the staging adheres to a tenet the company has followed throughout their twenty-year existence, what critic Sara Jane Bailes calls a process “not of adaptation, but of translation.”

ERS’ staging… presents the original text intact, in order, every last word of it, and provides visuals for the readership/viewership.

Artists reconfigure text-only material into visual and sound-based art forms all the time: fairy tales into musicals, novels into films, etc. In the logical first steps, the adapter converts prose into first-person dialogue. Descriptions become images. Blobs become actors. But instead of masking this transition, denying the text’s complete overhaul to better suit its new form, ERS gives translation the spotlight. It’s the equivalent of getting the wrong size hand-me-downs and wearing them anyway. Instead of making the necessary alterations, the show becomes about how and why the clothes don’t fit.

The cross-casting mentioned earlier intends to convey switches in time. Greig Sargent is Dilsey in 1898, Daphne Gaines is Dilsey in 1908, Vin Knight is Dilsey in 1928. If this seems confusing, it is. But all the Dilseys wear the same pink apron, so though Dilsey moves through bodies and voices, the characterization is clear. Casting Dilsey, a maid and woman of color in the early twentieth century South, across racial and gender divides, questions and complicates her role. When Knight, who also plays a few loudmouthed racist Compson men, takes his turn as Dilsey, a comment on parity not present in Faulkner’s text emerges through the pieces not fitting.

I find plays hard to read because I’m never sure how to visualize them. Do I pick a particular theatre where I’ve been before and stage the play there? In my head, what is my vantage point? Am I on the stage with the actors, or do I imagine everything from a seat in the audience? How do I keep the characters separate? Initially, I cast them as blobs, but then I can’t tell them apart, so then should I cast them as my friends? As celebrities? If the scene is on a golf course, do I construct a golf course set in my head, or do I picture an actual golf course?

All adaptation faces the criticism of unfaithfulness to its original. The journey from book to stage often lops off one’s favorite character, reduces descriptions of flowing landscapes to scrim and cardboard, replaces idyllic blobs with human faces, which, if I’m sitting in the back row, may still be blobby. Images that thrive in the imagination limp into reality. Previous ERS productions have paraphrased Tennessee Williams’s Summer and Smoke (Crab Legs), recast documentary films with actors (Total Fictional Lie), and staged the entire text of The Great Gatsby (Gatz). The common thread amongst the work, according to ERS artistic director John Collins, is “a very real human awkwardness put onstage.” Whereas, for instance, the Baz Luhrmann film version of Gatsby attempted to out-grand my grand visualizations of the novel, Collins undercuts them. His Gatsby is performed in a drab office. His Sound includes extended pauses, overlapping soundscapes, performers standing around with nothing to say. ERS productions revel in hiccups. Bodies trip and fall virtuosically.

In Sound, Susie Sokol, as Benjy, often sits center stage as others read her thoughts from a paperback: Aaron Landsman narrates a summer’s day from the couch; Tory Vasquez delivers a heartbreaking argument from a stool downstage left. Retaining all of Faulkner’s prose results in incessant repetition of proper names and the word “said.” “‘I’m not one of those women who can stand things,’ Mother said,” says Mother. What if every time you spoke, you reminded the listener who was speaking? “I don’t want to, the Reader said.” “But you have to, the Writer said.” Every outburst, complaint, and reassurance stamped with unreliable personhood, humanity underlined.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here