The article went on to talk to other activists, but I couldn’t get Mary’s words out of my head. “This is not your granddaddy’s civil rights movement.” Now I’m not quite old enough to be Mary’s grandmother, but I’m close enough to know she was talking about me. She was talking about the people I met as passionate revolutionaries, often dressed in Dashikis or overalls, who were, by the time she met them, respectable old men in suits and bespectacled women in sensible shoes who liked to talk about the good old days when Martin and Malcolm and Medgar walked the earth and they were young and strong and fearless. I felt the space between generations—the space between us—in a way I never had before and I didn’t like it one bit.

Being old is like when Sly and the Family Stone are singing “Dance to the Music,” and Sly’s little brother, Freddie, says, “Cynthia and Jerry got a message that’s sayin’…” And Cynthia says, “All the squares go home!” Now nobody who loves that song ever thinks they might be the squares she’s talking about. That’s what being old is like. The idea that we might actually be old is a thought we beat back with every once of our being until one day the years cannot be denied and there is more behind than in front and you realize you don’t want to learn what an “app” is, and the idea of Snapchat makes you break out in a cold sweat… And not in a good way. And suddenly “All the squares go home” means you!

When you’re young, you don’t worry much about communicating with an older generation unless they are in a position to grade you, or cast you, or offer you that dream job that pays well, satisfies your soul, and makes your grandmother so proud of you she can’t stop smiling. Otherwise, the older generation is presumed to be on the opposite side of most issues. Frightened by the future, dismissive of your concerns, quick to take over the conversation. Unwilling to listen.

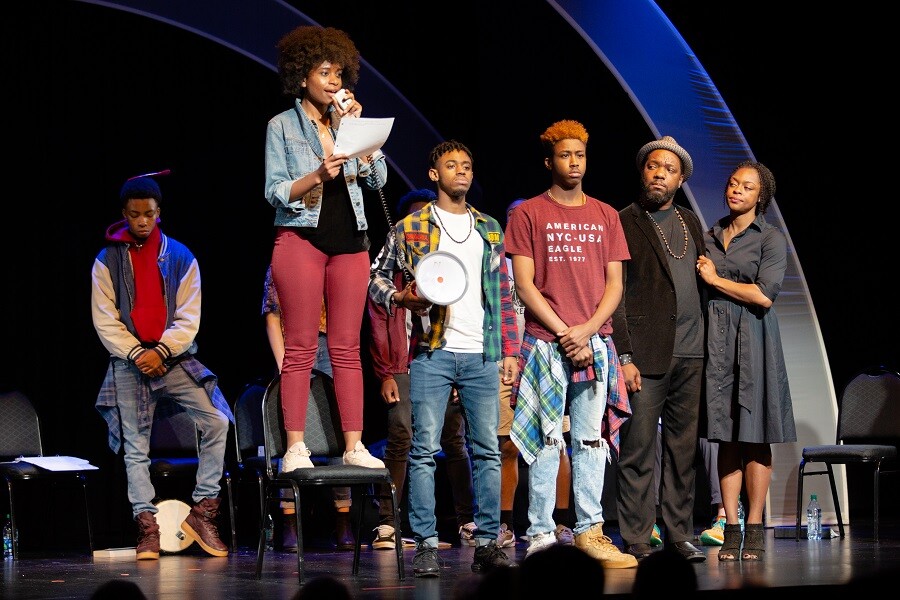

The young people, tired of being told to go slow or how we did it first and did it better, begin to tune us out. I remember that feeling. It was my generation that said “Don’t trust anyone over thirty” and meant it, so I do not take it personally if it is difficult for young people to listen deeply to those of us for whom thirty is a distant memory. So that is our challenge, yours and mine. We have to find a way to bridge that gap, to communicate honestly across all those years because our world and our country are in crisis and somebody has got to fix it and if not us, who? And if not now, when?

But I am a realist. I know there are undeniable obstacles and behaviors on both sides that those on the other side find difficult to deal with. Among the annoying things some old people will do when they talk to young people is mention their age all the time and then tell them it doesn’t matter. Of course it does! That’s not a value judgment. There is no “older and therefore wiser” implied. It’s simply a fact. Living sixty years is different than living twenty years, and if you’ve paid attention and kept your wits about you, you have probably seen some things worth seeing, been some things worth being, and learned some lessons worth passing on.

We have to find a way to bridge that gap, to communicate honestly across all those years because our world and our country are in crisis and somebody has got to fix it and if not us, who? And if not now, when?

At least this is the hope. Perhaps that is why we are so anxious to give them advice. Or perhaps it is because time is short and we want them to be ready for the not-too-far off future when the machines fail us and the environment reminds us in the most forceful terms that it’s not nice to take Mother Nature for granted and the world as we know it changes into a place we no longer recognize—a place where we scribble our secrets on scraps of paper, smuggled from hand to hand until they are worn and smudged beyond recognition and we must recite the words from memory, whispering them to each other like the prayers our grandmothers taught us to pray. Now I lay me down to sleep, I pray the Lord my Soul to keep. If I should die before I wake, I pray the Lord my Soul to take. Whispering in the soft, sweet darkness of nights we thought would never end. But they do…

Of course, they are free to evaluate any advice based on whether it makes sense to them or not. But before they decide, I hope they will consider that it is a love offering, a peace offering, a sometimes-desperate effort to be useful, to be relevant, to pass on all those hard-earned lessons when they turn their faces toward us, reluctantly, trapped in classrooms or church pews or lecture halls, when they sigh and say: “Okay, tell us what you know.”

And even though we’ve been waiting for them to ask, it usually takes us a minute to decide how much we are prepared to reveal about the complexity of the journey from whence those lessons emerged. It’s hard not to sanitize and analyze and minimize when you tell the story of your own life. We remember the high points. The moments of sacrifice and noble choices and personal victories. But we are less apt to want to share the details of the messiness that often accompanies the arrival of life-changing truths in those breakthrough moments when you step forward and spread your arms like that small child set down in front of the ocean for the first time, trying to grasp just the idea of it. The endless blue of it. The absolute shimmering essence of it. All of it. In that moment, we are sometimes reluctant to tell them the truth, the whole truth, and nothing but the truth.

A few years ago, I tried to whittle down everything I’ve learned over the course of my life into ten pieces of good advice that I could pass on to hopeful young people who asked me. They weren’t complicated ideas and I run through them here only because the reaction I got to Number 10 surprised me. Here they are:

- Work hard.

- Love harder.

- Eat your vegetables.

- Travel light.

- Pay cash.

- Be kind.

- Buy time, not stuff.

- Bring your own birth control.

- Register and vote in every election.

- Don’t lie, ever.

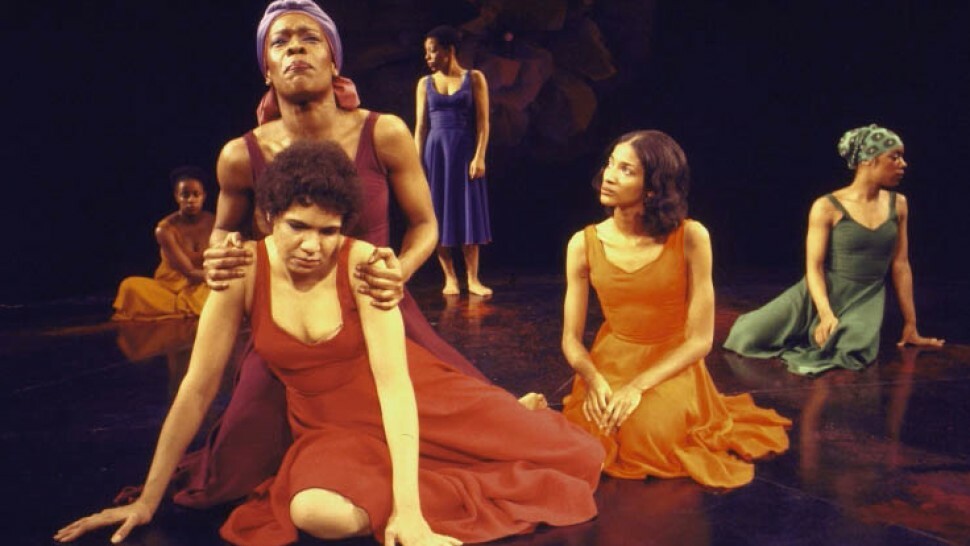

To my great surprise, the only one of my top ten that ever makes people hesitate is number ten: don’t lie, ever. They compliment me on one through nine and then immediately begin to propose exceptions to number ten. “Well, what if this…” and “What if that….” Some even went so far as to conjure up the final monologue of Ntozake Shange’s masterpiece, For Colored Girls Who Have Considered Suicide / When the Rainbow is Enuf, and asked me if I wouldn’t have lied to keep Beau Willie from dropping his children out of the window. So, for the record, if you are ever in the unspeakable position of having to negotiate with a psychopath in an effort to save innocent people, lie without ceasing and any higher power worthy of the name surely will forgive you. Always save the babies!

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here

Beautifully lyrical while being fierce and true. Thank you Pearl. Very inspiring

Deborah Burke