Conform-ation Bias

This kind of conversation overwhelmingly fall into the lap of women faculty and faculty of color. In researcher and archivist Zoe Mitchell’s case study of gender bias in higher education, she argues that female faculty are perceived as more nurturing, thoughtful, or caring. “Therefore,” Mitchell states, “students have a tendency to bring their emotional problems and needs—which can be entirely unrelated to courses or academics—to the attention of female professors much more often than male professors.”

Cultural conditioning is partially to blame for the disparity, but these behaviors tend to be reinforced by the very structures on which women faculty are evaluated. Teaching evaluations are often considered one of the most important assessments of a faculty member’s abilities, yet they do not actually measure teaching effectiveness. Political scientists Kristina M. W. Mitchell and Johnathan Martin found in their study of student evaluations of teachers that “students tend to comment on a woman’s appearance and personality far more often than a man’s” and that “women are referred to as ‘teacher’ more often than men, which indicates that students generally may have less professional respect for their female professors.”

This places women faculty in a catch-22. If they behave in a more “masculine” manner, they may see a reduction in their invisible labor, but that might come at the cost of being labeled as “rude” or “unapproachable” in their teaching evaluations. The system, then—even if it has been repeatedly proven to be faulty—encourages women faculty to perform in heteronormative ways. If they conform to the feminine norms of being caring, motherly, and empathetic, not only will they see more students coming to their door, but they may also receive higher teaching evaluations as a result.

How do we assist faculty who are tasked with this invisible labor, and how do we reduce their emotional fatigue in this practice?

Marginalized faculty are performing invisible labor at an even higher rate, as students with marginalized identities will seek out faculty who reflect that identity for guidance, even if they have never taken a course with that faculty member. Developmental educational psychologist and professor of education Manya Whitaker states in her article “The Unseen Labor of Mentoring”: “In each of these instances, I and other marginalized faculty are sought out because our identities make us safe and compassionate resources for students who’ve been—at best—let down by institutional policies and—at worst—punished by them.” This is especially true for marginalized faculty who are sought out to serve on diversity boards and asked to extend their service load beyond that of their cishet white counterparts.

In higher education, professorial labor is often neatly divided into three camps: research, teaching, and service. Even if higher education were to quantify the hours spent in (planned or unplanned) meetings with students, under which category would they fall? Are these invisible labor transactions an extension of teaching? Do these meetings fulfill service obligations to the department? How do we assist faculty who are tasked with this invisible labor, and how do we reduce their emotional fatigue in this practice?

Teaching with Transitional Objects

This past summer, I served as the artistic director for the Stephens College Summer Theatre Institute (STI), a six-week summer intensive for rising second-year students. Over the course of the program, the students created five performances in different specialties, ranging from long-form improv to Commedia dell’Arte to musical theatre. They were earning an entire semester’s worth of credits, which meant long days (and nights) in the theatre, seven days a week. Under these conditions, it was no surprise that, towards the end of the first week, burnout had begun to take effect and tensions had begun to build.

At the first STI company meeting, I had made it clear to the students that I, as the artistic director, was to be the point of contact for any and all personnel issues within the company. This meant that whenever issues did arise, students often came to me first to evaluate how to handle a situation and what (if any) assistance they needed from me in addressing it. While I would occasionally hear stories about conflict among and within the student company members, I would more often hear the signs of burnout from my students, like fatigue, detachment, and insomnia. In these cases, I realized the students didn’t have a problem for me to solve, what they wanted was comfort.

A few weeks prior to the start of STI, I had completed my doctorate from University of Missouri. As a celebratory gesture, one of my colleagues gave me an unusual graduation present: a giant stuffed Bulbasaur. For those unfamiliar, Bulbasaur is the first Pokémon and is a fusion of a dinosaur and a giant plant bulb. (While this present may seem odd to others, those who know me know that I am an avid fan.) This Bulbasaur was everything one could want in a stuffed animal—it smiles, is soft, and anyone could fully wrap their arms around it for a big squeeze.

By implementing a transitional comfort item into my pedagogy, I was able to establish professional boundaries with my students and delegate invisible labor.

Knowing my students were particularly stressed, I decided to bring Bulbasaur into my office and let the students know it was available for use should anyone need some comfort. I thought the students would see the gesture as silly on my part and that Bulbasaur would simply occupy a chair in my office for the duration of the six weeks. I was completely wrong.

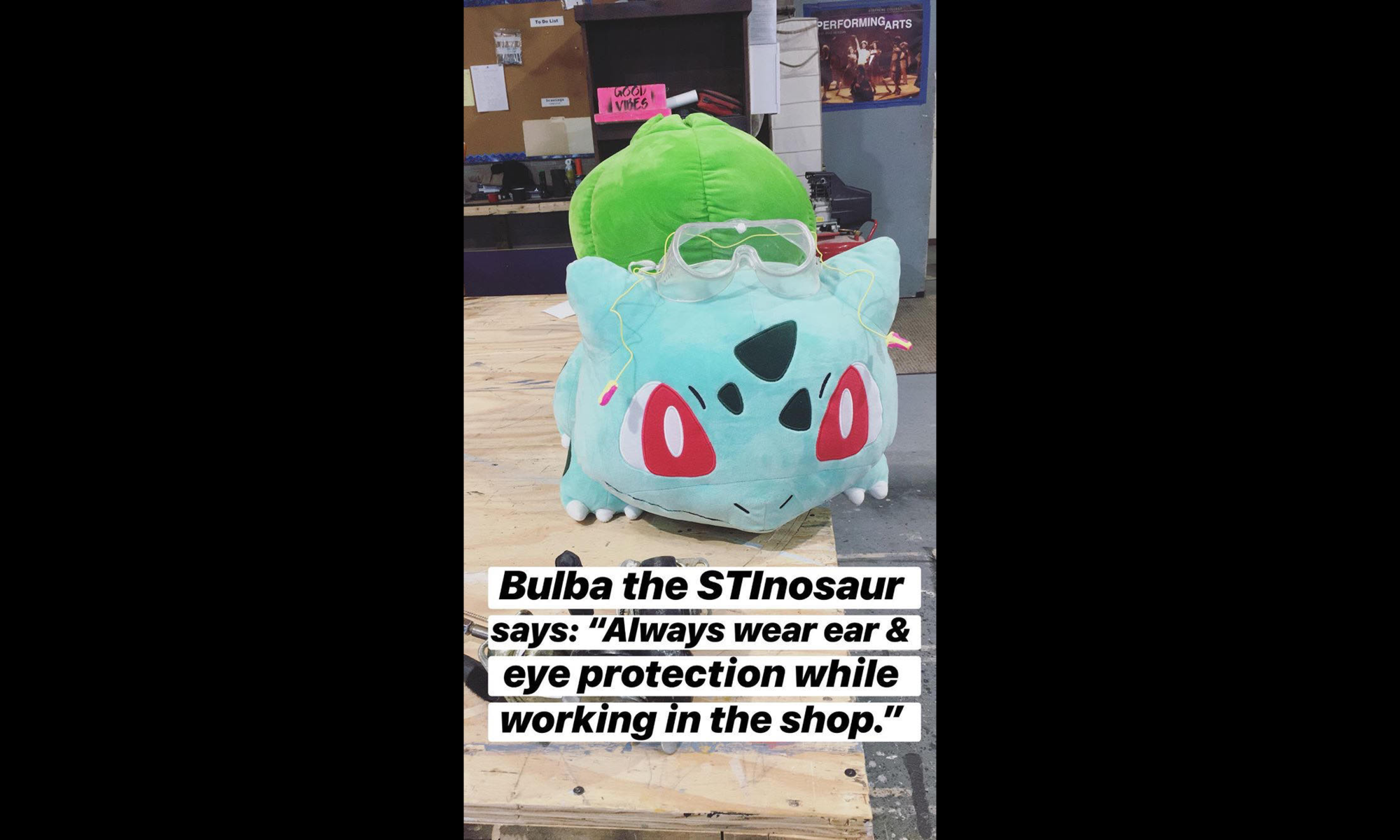

Every single day, students would swing by to give Bulbasaur (or “Bulba the STInosaur” as “he” became known) a quick squeeze between classes, take him to rehearsals, and have him “supervise” light hang and focus. It turns out Bulbasaur functioned as what psychologists refer to as a “transitional object,” which provide comfort in times of stress. While most people will associate these objects with childhood, humans use transitional objects—which include cherished items from loved ones and pets that keep us company when we are feeling down—in all stages of life. While bringing Bulbasaur to my students was a small gesture on my part, it had an unintended consequence. By implementing a transitional comfort item into my pedagogy, I was able to establish professional boundaries with my students and delegate invisible labor to a stuffed animal.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here

Dear Kate,

I loved reading your piece–and I really, really enjoyed the suggestion of the transitional object. I just got a Yoshi for Christmas, and I think he'll be joining me in my office hours soon! I don't get approached quite the same way as you do, one because I'm a cis-man, but I'm legibly queer and I'm a graduate student so my students tend to approach me for comfort (or validation?) as well. And also, as someone who's definitely asked a lot of emotional labor from his faculty since high school: THANK YOU for all you do for your students.

–Khristián

Hi Khristián,

Thank you so much for your comment! Yoshi is always my favorite when playing Super Smash Bros. as a kid, so I highly approve of your choice!

Absolutely, without a doubt, queer, trans, and non-conforming folx are included in the category of marginalized faculty. I am sure you facilitate many conversations with students questioning aspects of their identity and sexuality! THANK YOU for your contribution and being a support to your students!

Kate