Interview with Theatre Three’s Executive Producer-Director Jac Alder

The Dallas Series explores the challenges and rewards of creating theatre in Big D. Join us this week as we journey deeper into the heart of Texas.

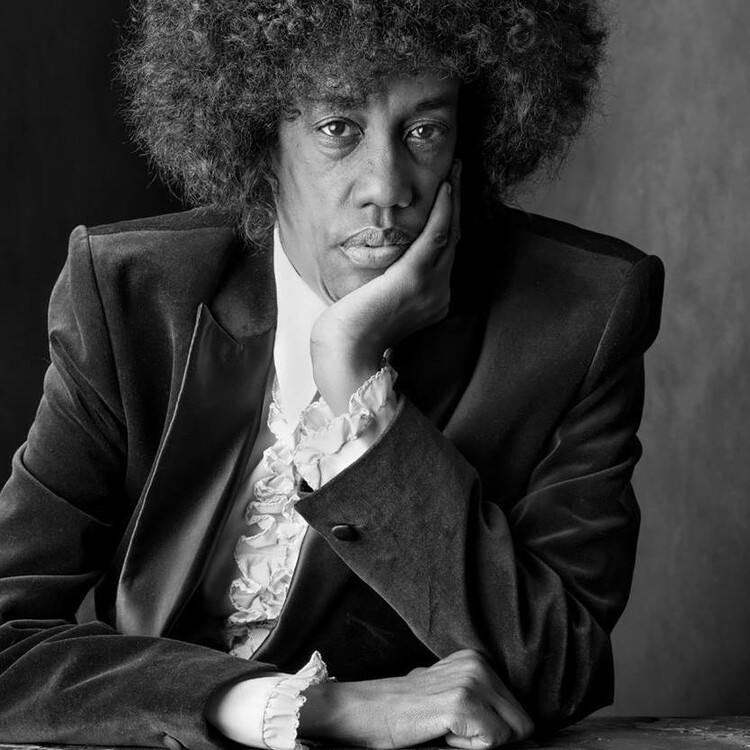

Jac Alder is Theatre Three’s Executive Producer-Director. Jac and his wife, the late Norma Young, founded Theatre Three in 1961. Norma was inspired by her work with the Alley Theatre’s Nina Vance to create a theatre that celebrates the playwright, actor, and the audience—hence the name Theatre Three. Theatre Three is a cornerstone of the Dallas theatre community and performs in a wonderfully versatile 242-seat theatre in the round.

In this interview we discuss the challenges facing the Dallas arts community, Theatre Three’s history and downsizing, and how it opened new doors of opportunity for Theatre Three.

We start by discussing the Artsetters Master Class, a Dallas Arts Week event Jac spoke at on April 7 at the Nasher Sculpture Center.

Jac Alder: Well you know I was on my best behavior the other night. And I’m through with that shit. (laughs)

Jonathan Norton: Okay now! (more laughter) Can I say “I’m through with that shit?”

Jac: Well I can say it. I don’t care that it’s being recorded. As long as you also record the fact that I’m laughing.

Jonathan: Okay.

Jac: I was just really nice when I was honored at that thing the other night, and I thought I painted too rosy a picture. Here we are in silos as organizations in Dallas and we’re not really into the collaboration that should be here. There’s a lot to fix in our local arts ecology.

Jonathan: Such as?

Jac: There is nothing structural in the city right now that gathers together the people that program the arts on any sort of regular basis, not even once a year, to say, what are you up to? Even informally. Or what shows are you playing or what experiences have you had there. Or going back—and I hate to be such an old timer— but going back to the time when basically there was the symphony, there was the opera, there was the Dallas Theater Center, and there was Theatre Three. There were a smaller number of arts entities. We all got together and collaborated on the idea that we would have a common mailing list. This was called the Dallas Arts Combine at the time. And so the organizations met to work on a rather specific problem. But because we were together in the same room, other kinds of collaborations came together. I used to narrate the childrens’ performances of the opera. I used to narrate the childrens’ performances of the Dallas Symphony. There were these crossover things because the artistic personnel met and had a chance to discuss other issues. There is nothing like that now. There is nothing structural. And I have said to the Office of Cultural Affairs and I have said to the commissioners and I have said to the Center for Nonprofit Management, isn’t something missing? I think somebody should organize a chance for the outfits to sit down even without an agenda every once in a while.

Jonathan: We talked earlier about your own personal activism in regards to civil rights. Can you speak about how that influenced Theatre Three’s programming?

Jac: We did plays by black playwrights. Ossie Davis’ Purlie Victorious was the first play I directed in 1961. Race is a dramatic subject so it was as much out of reflecting current literature for the stage as it was trying to “make points” for civil rights that we produced polemics like In White America as well as featuring plays about the black experience in dramatic situations like Member of the Wedding. We used black actors in roles originally written for white actors before there was the—to me, flawed—practice of color-blind casting. Billy McGhee played both in Emperor Jones (where the point was that he was a black man) and the jazz musician in The Tender Trap where ethnicity was not an issue. We produced three of August Wilson’s plays, the first we produced before he won the Pulitzer Prizes. We included plays like For Colored Girls, which is as much about gender politics as racial politics. We got to know many particularly gifted actors of color, and sought plays for them to be in. So it was talent driven along with being politically driven. We helped Dallas Minority Theatre get started because we knew the founders because they’d worked for us. We did joint venture with Dallas Black Dance Theatre in its early days. The season of assassinations of Kennedy, King, Kennedy did force a very conservative Dallas to somewhat mitigate its racism. But this was happening nationally.

Jonathan: Can we talk a bit about the history of Theatre Three? First of all, is it true that you are the longest serving artistic director in the United States?

Jac: I think that I’m the longest serving as in the longest serving theatre founder in the country. I have never used the title artistic director. Norma [Young] had that title. I’ve been known as Founding Producer-Director.

Jonathan: I understand that Norma was inspired by the work of Nina Vance of Houston’s Alley Theatre. Was there a relationship with Margo Jones as well?

Jac: Norma was a native of Dallas, but never worked for Margo. She did, however, join the staff of the Alley as a stage manager, teacher to their Merry-Go-Round Academy, and actress. Norma recruited me along with Esther Ragland and Bob Dracup to start a theatre pretty much on the same business and operational model as the Alley. Dallas had loved Margo and her operation and here was another woman doing theatre in the round. So the public, even including the media, made associations with Margo that weren’t quite accurate. Margo was intensely focused on doing brand new works along with some classics. Our inclination was to program across a broader spectrum of the stage literature that could be called closer to the philosophy of the Alley.

Jonathan: In what ways has Theatre Three changed over the years? I believe when I did Joe Turner’s Come and Gone, Theatre Three was a LORT house. It was a LORT D. I don’t believe it’s still LORT.

Jac: No. In the meantime they developed a more appropriate contract called an SPT, Small Professional Theater contract, which met our needs rather better. I don’t remember this. You might. How many performances a week were we doing back in Joe Turner’s?

Jonathan: Oh gosh. That was eight performances a week.

Jac: Yeah, that’s what I thought, and there simply wasn’t the ability in this market to sell eight performances a week. It didn’t work. So the LORT model for us at the time was one of the issues that was working against us, because we were given a nonprofessional/professional ratio that was suitable. But even the Equity members in this jurisdiction didn’t have daytime availability for rehearsals and the LORT model required daytime rehearsals. Well, that isn’t possible. It still isn’t for us. So we welcomed the fact that there were SPT contracts. However, I have to say, I am a firm believer in having good union rules. But those always have to come under scrutiny too, because again you have the thing of a national model that may not fit some local needs for whatever reason and the local needs may vary even from one institution to the other.

Jonathan: In speaking of going from LORT to SPT, have there been other ways or times in the history or Theatre Three in which it became necessary to downsize and what was the result?

Jac: Definitely downsizing has been way too much part of the dialogue in some ways and we’ve had our own wrestling match trying to figure out how to make the Theatre Too space work. The Theatre Too space came about because we had a rehearsal hall that more than thirty different organizations and artists had produced in. They came to us and said if you’re not using the rehearsal hall during this time can I do this one-person show or can my company come in and do this show. So when Terry Dobson (Theatre Three’s Musical Director and Company Manager) came to me and said to me, you know I Love You. You’re Perfect. Now Change could have a longer run. Maybe we should move it over into one of these other spaces here in the Quadrangle. I said if we’re going to set up a theatre, we need to do it down in our basement space and just see how long it runs. Well, the damn thing ran three years. And Terry said, “Hello, we’ve really solved a big thing here about how to have actors continuously under contract, making money, to continuously have something for the public to come and see.”

But the first thing we did after that was a series of plays. We tried a reading series. We tried all sorts of things. Then that operation needed to be subsidized more than we had available because we needed subsidy for the shows upstairs. So we took a big risk and it paid off and we reconfigured the space slightly, including creating a backstage in what had been the telemarketing department. We outsourced telemarketing. We no longer have in-house telemarketing. And we put Avenue Q down there to see if we could get another long run, which we did—almost a year. And that’s the right model. You keep actors working with long runs, and then you always have something to offer the public.

Definitely downsizing has been way too much part of the dialogue in some ways and we’ve had our own wrestling match trying to figure out how to make the Theatre Too space work. The Theatre Too space came about because we had a rehearsal hall that more than thirty different organizations and artists had produced in. They came to us and said if you’re not using the rehearsal hall during this time can I do this one-person show or can my company come in and do this show.

Jonathan: For me, one of the great hallmarks of Theatre Three is the artists that you have developed over the years.

Jac: Well, let’s start with the fact that we’ve had three Pulitzer Prize winning playwrights come from this theatre. Yeah, let’s start with that. Beth Henley for Crimes of the Heart. Then, I Am My Own Wife by Doug Wright. And then, August, Osage County was written by a young man who never had a role in a major show here. But while he was in town we had a reading of new plays down at the library and he was one of our readers. Which is kind of wonderful.

Jonathan: Wait. Tracey Letts?

Jac: Tracey Letts.

Jonathan: No way!

Jac: Yeah. Three Pulitzer Prize winners from Theatre Three.

Jonathan: I would be remiss if I did not ask about the late, great Larry O’Dwyer, who died earlier this year. How did you come to meet Larry?

Jac: Larry worked with us first in a Molière’s Physician in Spite of Himself in ’63, I think, and he was so hugely talented and special that he became a very important component of the staff, such as it was in those early days. What so many people don’t know is how wonderfully he worked in children’s theatre for us—writing, directing, performing. He was magic to the kids. As we got into the eighties, there were very few years he didn’t get some kind of outside gig like teaching at Bennington or other away-from-Dallas work. Stephen Wadsworth, a great classical director, saw him in Wholly Molière and hired him away from Dallas for shows in all sorts of major cities. He was seen in one of Stephen’s shows by Baltimore CenterStage, where he was an associate artist from about 2005.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here

Thank you for this wonderful interview.

Great interview Jonathan! Love, love, love Jac Alder.