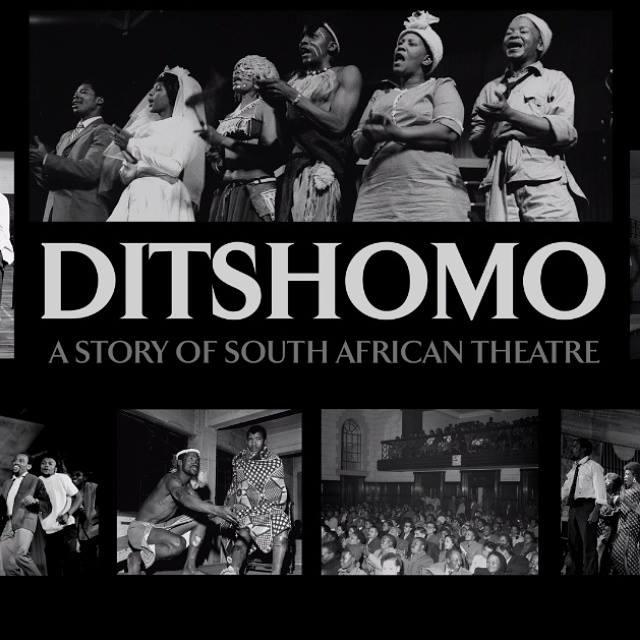

Ditshomo

The Story of South African Theatre

This week on HowlRound, we cast our gaze across oceans towards the world of South African theatre. A nation characterized by its Apartheid legacy and struggle for liberation, we hear the story of a nation reborn and the art at its center through the voices of some of its most dynamic artists. Find the full series here.

Grandmother: Long… long time ago in the land of nothing…

This is how my grandmother would begin to tell us Ditshomo (stories) with me and my siblings rolled up around the fire and the stars of the wide African skies watching us with their sparking eyes. We would wait in anticipation for the voice of the storyteller to embody all animals and giants in the world. And when we were asked if the story should continue all children would respond with a clicking sound, affirming that we are indeed ready to hear Ditshomo.

Gandmother: Ba re ene ere (Once upon a time).

The Children: Qhoiiiii! (Tell us the story).

From ancient time our grandmothers and mothers shared stories of heros and villians, of morality and cultural values. Our grandfathers and fathers led the ritual naming from our family trees. It took the whole village to raise a child. So it was a communal responsibility to send girls and boys to initiation schools to learn about humanity, love, sexuality, politics, and wars. Time was spent teaching and reminding us who our forefathers were, through oral traditions.

So whether history has documented this information or not, we all grew up with Ditshomo enbedded in our blood. We knew who we were from stories, poems, songs, and dance. That we were and still are living theatre and walking libraries. That the stage has always been our backyard. The fire between us and the storyteller is a convention that sets up Ditshomo Tsa Rona (our stories).

The First Black Ninja Girl

The history of our oral tradition means that our theatre has long existed even before ancient Greek theatre. So it is no wonder why as a child I dreamed of being the “The First Black Ninja Girl” in the world. And with my father, who was a teacher, a visual artist, and a collector of African literature, it made it easy for me to believe in all kinds of Ditshomo. My mother, a lover of books and a good storyteller, shared with me all Sesotho folklore—fairy tales, fables, and the richness of our language (idioms, riddles, and proverbs). Though I was born in Soweto, which was the township, my father decided we would move to QwaQwa a rural area, after the 1970s uprising.

QwaQwa, named by the San People, either refers to the snow tears in winter, or the droppings of vultures that leave snow-white markings on the sandstone. This homeland with beautiful trees, small muddy rivers, and the golden-red gigantic mountains became a hub of my childhood stories.

As a teenager I was influenced by my Sesotho culture and lived in a home where it was a norm to play chess or read the Sunday Times newspaper every Sunday after church. Later, I ventured into books and discovered that I could escape the dry dust bowl that was a failed apartheid experiment in South Africa inside these stories. I read everything my eyes could catch, Sesotho classics from Nna Ke Mang? by K. P. D Maphalla, to Sergeant Kokobela by K. E. Ntsane. I fortified myself with the little Bantu Education English and slowly moved to Chinua Achebe’s Things Fall Apart and Ngugi Wa Thiongo’s Devil On The Cross, which gave birth to multiple voices in my writing, theatre plays, and storytelling.

The Disobedience of a Theatremaker

Moving back to Johannesburg in the mid-90s, I realized that I was part of two South African worlds: one that was epitomized by apartheid and the other which was the dawn of its freedom. For three years at the drama school I was taught that the origins of theatre go as far back as classical Athens in the 6th century BC. The course further attesteded that early theatre has Aristotle, who in his Poetics defined theatre in contrast to the performance of sacred mysteries. So I constantly asked myself, what about the origins of African theatre? What about Ditshomo Tsa Batho (stories of the people)? There were no stories that reflected the voices of my grandmother, mother, aunts, and sisters on any South African stages.

It was women that have been been the true custodians of Ditshomo. Our grandmothers and mothers allowed our children to dream and live inside the magic world of oral tradition.

Photo courtesy of Napo Masheane.

Black Women in South African Theatre

In the mainstream theatre I found that there was little said about the state of black women in South African theatre. Most of the documented works were done during the 70s and 80s, where male poets/playwrights such as Ingoapeleng Modingoane, Matsemela Manaka, Maishe Mapoya, Sipho Sephamla, and many more used theatre as a protest tool. The failed relationships between black and white South Africans gave these writers no option but to write about the racial discrimination. But as a student of a black consciousness, where were the black female protest writers and poets?

In the recent past the theatre industry has been dominated by two groups of people: white theatre practitioners and black men. Progress has been made in empowering and developing black women to be in executive, management, and decision making positions mainly in politics and the corporate sector, but within the South African performing industry there has been no such progress.

As a female story teller I knew it was women that had been been the true custodians of Ditshomo. They captured our imagination with the beauty of language, style, and form. Our grandmothers and mothers allowed our children to dream and live inside the magic world of oral tradition.

The stage has always been our backyard. The fire between us and the storyteller is a convention that sets up Ditshomo Tsa Rona (our stories).

Ditshomo: A Story of South African Theatre

Beyond the gender inequality that exists in the theatre industry, there is a huge misconception regarding the origins of South African theatre. That led me and a team of friends to make a documentary called Ditshomo: A Story of South African Theatre. Through its production we met and led conversations with numbers of South African thespians and storytellers who took me back to their childhood memories in terms of our theatre.

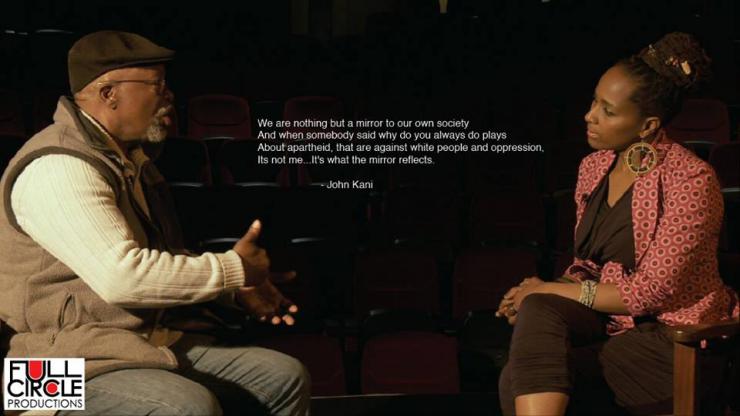

At the beginning of this epic documentary Dr. John Kani sets the tone, chronicling the story of South African theatre by touching on the effect that the stage has on the psyche of an oppressed people:

The theatre of the past was driven by the passion for human dignity, respect, equality, and justice. We used to say that if the roses and tulips grow in the madam’s garden in Houghton, they can also grow in Kliptown, Soweto, and Alex as well; flowers that celebrate our own humanity and dignity. That was our theatre.

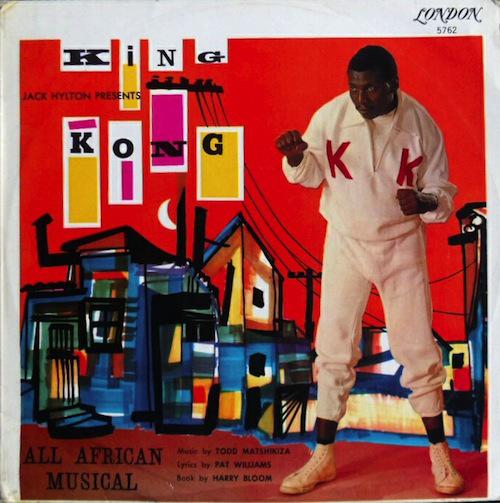

And so the journey begins delving into the roots that extend to a period before the protest theatres that Kani mentions. Ditshomo interrogates the very controversial genesis of black theatre looking at the works that preceded King Kong, the 1959 South African musical about a heavyweight boxer, Ezekiel Dlamini, which is usually the first reference point when tracing the black experience on stage. Theatre producer, Matjemela Motloung clarifies the reasoning for King Kong’s prominence in people’s minds outside of its artistic excellence:

King Kong became the success it became because it had access to whiteness. Those who were involved in it were friends with the Helen Suzamans [South African anti-apartheid activist who died in 2009] of this world and you realize that it became the success that it was because of this access and it was appreciated differently than Sponono by Alan Paton and Krishna Shah, Sikhalo (1966), and Bopha! (1986) By Percy Mtwa.

Ditshomo: A Story Of South African Theatre reminded me as a theatremaker that my poems and plays usually arrive in me as pure SONGS (Dipina) or a CRY (Kodiyamalla). Sometimes their inspiration springs from traditional family rituals, as a PRAISE song/s (dithoko/thoko), or from a simple memory of a childhood church song, a HYMN (difela/sefela). Most times these words present themselves as a source of where one comes from, CLAN NAMES (seboko/poko). So my plays find me in the dusty streets of my village and township. And like Pablo Neruda:

I don’t know, I don’t know where

It came from, I don’t know how or when...

But from a street it called me

From the branches of night…

There it was without a face

And it touched me

Closing Reflections

My journey into theatre and spoken word has always been a mixture of talent and the need to share Ditshomo Tsa Rona (Our Stories). Silence scared me, so I write not because I want or have to, but because if I don’t write the world will not hear stories from our township corners. If we who graced these streets do not capture its memory and print out in words its snapshots, those memories will be lost. Echoes of my township stories like Ditshomo spoke to me when I wrote: My Bum Is Genetic Deal With It, Fat Black Women Sing, Hair & Comb, Street Lights With Lips, and A New Song.

Through Ditshomo: A Story of South African I see how each storyteller must heed the call and carry that baton of experience forward and beyond the grave. There isn’t one explanation of poetry/spoken word/play/theatre/story telling when it comes to defining the origin of South African theatre. But what I know is that my poetry and plays have allowed me to share parts of my world without fear of experimenting with language and exploring different themes. It is through the resistance to fit into a box as a label, that I disobey. My work as a poet and a playwright is to make sure that my words not only live on page, but also stand strong on stage so our Ditshomo are told and perfomed, so it can live long after we are gone.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here