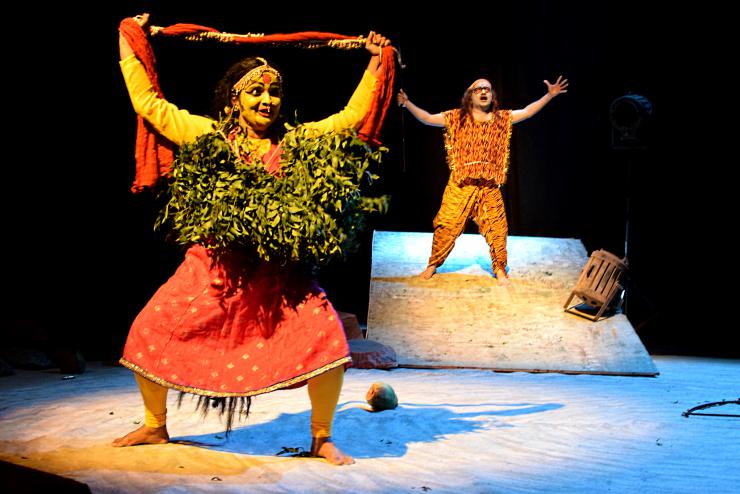

Dweepa (The Island)

A play with beginnings in the questions of Climate Change

This week on HowlRound we continue our exploration of Theatre in the Age of Climate Change, begun a year ago, in honor of Earth Week 2016. How does our work reflect on, and responds to, the challenges brought on by a warming climate? How can we participate in the global conversation about what the future should look like, and do so in a way that is both inspiring and artistically rewarding? South-Asian playwright Abhishek Majumbar discusses the questions that lead him to write his play Dweepa. —Chantal Bilodeau

In 2014, the subject of ecological philosophy made its way from a bookshelf to my study table.

Having been a student of environmental economics earlier, the various scientific, social, and eco-political debates were not new to me, but despite the urgency of the situation, I had never wanted to make theatre about this subject.

My enquiry was framed by a simple question: 'Why are we causing harm to the planet, when we are absolutely certain that it is unfailingly counter-intuitive to rock the boat one is sailing in?'

It was eco-philosophy that made me wonder about addressing our ecological crisis in the theatre. My enquiry was framed by a simple question: “Why are we causing harm to the planet, when we are absolutely certain that it is unfailingly counter-intuitive to rock the boat one is sailing in?”

Of course there are some common answers to this question that include words such as development and short–sightedness, but I had never found these answers satisfactory since they suspiciously point more towards the symptoms than the real issue. They lead us to the next question: “Why are we insistent on rocking the boat we are sailing in, in the name of developing a machine of higher grade?” The answer to this question is in fact even more obvious than the first one’s.

What is curious is that in the Indian subcontinent, like in many other mytho-centric civilizations, the environment is sacred. It is not an abstract, scientific concept, nor is it an absolute science to be understood and controlled. In fact, the subcontinent is replete with living mythology and oral histories through which a community or individual is absolutely connected to the environment. In such a scenario, how to ask the question of why we are harming the planet was the key enquiry during the making of Dweepa.

I went through one and half years of climate change data, interviewed scientists who worked with live satellite data, studied specific communities in mountains and coastal villages in Bengal, and immersed myself in East Indian mythology. The struggle to find the deepest reason continued for more than a year with the drafts of the play looking more and more like other scientific documentary presentations.

The breakthrough came from a few concurrent sources: From Felix Guattari’s book The Three Ecologies, from Ramachandra Guha’s work on ecological philosophy in India, from a Kannada-language film called Dweepa by Girish Kasaravalli and finally from a piece of music by guitarist and composer Susmit Sen called “Depths of the Ocean.”

India is a land of multiple traditions and multiple modernities. There is the obvious modernity of the urban folk, the technological boom, and reliance on the environment merely as a distant provider in one’s day-to-day life. However, a deeper look into the many communities that exist within the urban middle class shows us that in mythology and in religion, the environment exists as a provider in a larger sense. People who otherwise have very little to do with the environment, on several occasions throughout the year, worship nature in some form or another.

In rural areas, particularly in forest and agricultural belts, this is even more true. In eastern India, even if we only take the Sundarban forests as an example, people pray to “Bon Bibi” the goddess of the forest, before entering the thicker parts. A large part of the Sundarbans becomes completely submerged during the monsoon, and reappears in the winter.

People’s entire livelihood and life itself is concretely connected with the submergence and reappearance of the forest and its connection with other animals. However, in the last decade or so, due to sea level rise, thirty percent of the submerged forest has not reappeared. A land mass a few times the size of New York City is permanently lost.

Fisherfolk in and around the Indian subcontinent have increasingly been arrested by neighboring maritime police. Srilankan, Indian, Pakistani and Bangladeshi fisherfolk have more often than ever been found crossing nautical boundaries and have consequently been languishing in foreign jails for years.

A major reason for this is that, due to global warming, the salinity of the water around the coasts has changed and fish that used to be found say 2km from the shore have now moved 7 km away, further out in the ocean.

There are prayers for going out on the ocean, prayers and rituals for a safe return, prayers for a good catch, but in the face of anthropogenic global warming both fish and gods seem to have changed their minds.

In Bengaluru’s Visvesvaraya Industrial and Technological Museum, a live data feed from 300 satellites shows us the movement of oceanic heat waves by the minute.

Technology is there to forewarn against tsunamis and yet anyone who has ever lived through a tsunami knows that almost all animals deserted the shores before the tsunami hit land. How did they know? Which technology or which god gave them this premonition?

These questions and research form the basis of the play.

The play itself has been playing across Karnataka in south India in Kannada, the language of the state. Audiences’ reactions have been mixed to say the least.

Sometimes the blending of mythology and technology is viewed with suspicion, but overall there are wonderful post-performance conversations about the themes presented in the play. Particularly in non-metropolitan cities, audiences are deeply aware of the connection between gods and satellites.

At best, the play makes the conversation happen but does it bring a change? I do not know. In a country obsessed with development, where the GDP and the rate of economic growth don’t match up to farmer suicides and child malnourishment, isn’t it time for us to rethink our position on this planet, not as a culture that apes the developed West but as leaders that propose new models? Models that bind our inner lives to our outer desires. For this, there are innumerable stories, present in the subcontinent. Dweepa happens to be another one.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here