Grusomhetens Teater

Cruelty and Entertainment

While theatre artists around the world may all know A Doll’s House and Hedda Gabler, few are as familiar with what is happening in contemporary Norwegian theatre today. In the Beyond Ibsen series, American expatriate and theatre producer Brendan McCall profiles some of the diverse artists working today in Henrik Ibsen’s birthplace.

“Look at this! This is horrible!”

Lars Øyno is pointing at the wall of his office, the sleeve of his black suit hanging off of his slender arm. Over the weekend, there’s been some water damage from the ceiling, falling onto his desktop computer and some books. He trembles with annoyance. Oslo Kommune, the city municipality, just completed renovations on the black box theatre that has been his home since 2002. While extremely grateful for the support, the renovations went a number of months longer than expected, causing a number of disruptions to his theatre’s operations. This seems to be one more straw, threatening to break the camel’s back.

“Can you please take some pictures of this, and send them to me?”

I click a few pictures of the office with my smartphone, and email them to him before replacing it in my pocket. Øyno’s “burner phone” is only good for calls and texts. His desktop computer connects to the internet through a cable. To the mild exasperation of his company members, there is no WiFi at Grusomhetens Teater—which translates as “the theatre of cruelty” in Norwegian.

Once, Øyno told me that when writing a new manuscript to direct, he goes to his cabin in the woods and writes by candlelight. His work is done for the day once the candle burns all the way down, and is extinguished.

Put that anarchy into the artwork. Put that kind of madness into it. That is working with the form.

Some criticize Øyno and his company as being old-fashioned, quaint. While European contemporary theatre is becoming increasingly hybrid and cross-disciplinary, Norway’s cruel theatre is rooted in the Artaudian tradition. Since choosing to leave a successful career as a stage, film, and television actor and lead this independent company in 1992, Øyno has directed twenty-six full-length productions. Clearly Øyno likes “the old ways,” and doesn’t see a reason to change his process of creating theatre, which connects chaos with the metaphysical.

“You cannot have art,” Øyno asserts, “without working with form.”

As he continues talking about the work of Grusomhetens Teater, Øyno often references ideas posited by the influential and controversial theatre artist Antonin Artaud (1896-1948). Essays such as “No More Masterpieces”, “The Theatre of Cruelty”, and others from Artaud’s seminal Theater and Its Double (1938) inform much of the philosophy underlying the Norwegian theatre of cruelty’s work.

“Artaud knew that there are some possibilities in free behavior,” he goes on, referring to naturalistic theatrical traditions and acting styles.

But without limits, it is not worth anything. So Artaud wanted a kind of anarchistic, chaotic situation, but within frames, with strict rules. And then they will be powerful. That is to say, put that anarchy into the artwork. Put that kind of madness into it. That is working with the form.

Over a quarter-century as director and artistic leader of Grusomhetens Teater, Øyno has framed that creative chaos through a variety of theatrical performances. These have been presented by a number of festivals and venues in Europe, Asia, and most recently, the United States, and have earned him and the company a number of awards. While trained in traditional acting methods from Norway’s prestigious Oslo National Academy of the Arts, most of Øyno’s productions do not use spoken dialogue. Often, a new work begins with an idea or a series of images. “I build up from scratch, onstage,” he says.

I walk a little bit towards that image I have in my head. I can see some basic steps I think could be possible in this process, which will move towards the final image I want to create, and that I want the audience to see onstage when it is finished. I try to fix some patterns, some movements. Some steps, some details that are fixed. Out of that fixed situation, the actors find some movements or patterns.

'I think that some of the importance with the kind of work we do, connected with Artaud […] is to bring something forward which is not so common, to make that visible.'

His actors train regularly throughout the nine-week rehearsal process in physical and vocal methods borrowed from the Polish Laboratory Theatre, particularly Zygmut Molik and Rena Mirecka. There are no auditions for Grusomhetens Teater: Typically, Øyno invites actors to participate in a production after they have successfully studied with him in his workshops, which are offered in Oslo twice per year. This Grotowski-based foundation for the ensemble to work in provides a common vocabulary between actor and director, as well as a distinctive aesthetic threading through the company’s work as a whole.

“I think that some of the importance with the kind of work we do, connected with Artaud,” he says, “is to bring something forward which is not so common, to make that visible.”

In addition to original works conceived by Øyno, Grusomhetens Teater also has the distinction of having produced not one, but two world premiere productions by Henrik Ibsen: the 1860 prose comedy Svanhild (2014), which won that year’s Oslo Prize for Best Performance; and the 1859 opera Fjeldfuglen (2009), featuring an original score by Filip Sande, and which heralded their North American debut this past March at the Ellen Stewart Theatre at La MaMa in New York City. Both are frequently re-staged within the company’s repertoire, often popular amongst critics and international audiences alike.

“Theatre must also entertain, or it would be deadly serious—which is extremely boring,” Øyno declares. He does not subscribe to the stereotype that physical theatre serves only as a catharsis for those onstage, remaining obscure to the majority of audiences.

“We don’t want to suppress or put people down, say that everything is very dark,” he says, shaking his head. “That is already around us, all of these depressing stories.” Øyno believes that this sort of indulgent, ultra-serious theatre was never Artaud’s intention.

Artaud saw that theatre was a kind of fascinating spectacle for people. He wanted his theatre to be open to let people laugh, have fun, be entertained. That is very important here. Or else the theatre of cruelty cannot exist. It’s okay to be serious. But what you deliver to the audience must entertain.

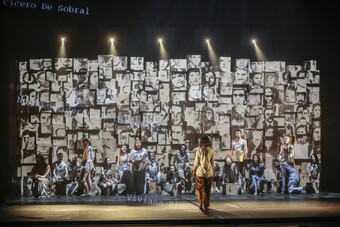

Currently, Grusomhetens Teater is preparing for their third tour to Tokyo in as many years, with Øyno’s latest original production “I is another”—Rimbaud in Africa (2017), an abstract work about the transformation of a poet into a businessman. Svanhild will be presented again for the first time since the summer of 2015, when it was performed at the Oslo Opera House. The group is currently finalizing their return engagement to La MaMa. And shortly before Christmas, Grusomhetens Teater will present the world premiere of Judith Malina’s Venus & Mars, presented as a co-production with members of New York’s Living Theatre.

And yet, despite these accomplishments, Øyno often feels that Grusomhetens Teater is perpetually on the brink of closing its doors forever. The group’s economy is perpetually precarious, with survival largely dependent on applying annually for support on a project-by-project basis. The group has its share of supporters and admirers, particularly abroad; but at home there are those that believe that Øyno and his colleagues are “out of step,” a relic from a bygone era.

Does Øyno feel like he wishes he lived in a different time or place, where there was more support for his theatre?

“Oh no,” he says with a wolfish grin. “I have to be in this conventional fucking static society of Norway. Because here I can do some more damage.”

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here

Love from The Living.

inspirational and heartening in a world where this is unexpected. thank you

A truly good piece of writing, the indication that Grusomhetens is about to close down is quite disheartening. The poetic theatre of Oyno has the charming music and rhythmic light also. Hope you will continue writing about the recent productions....